SHIROBAI !

Odds Are Against The Japanese Cycle Cop

YUKIO KURODA

YOU OFTEN see him sitting beside the road, his eyes hard behind sunglasses, as he watches the passing traffic. He’s liable to come up behind you, bring you over and give you a real talking to. And when he does, he will address you in a stern, gruff voice as omae, the word for “you” used for infants, pets, criminals or dangerous speeders. He has a tough job, and he isn’t paid much to do it. He’s a Japanese motorcycle cop, and because of the white (shiroi) color of his bike (bai) whenever you spot him you think “shirobai!!”

Japanese traffic is possibly the most hideous in the world. Japan had no notion of wide, paved streets until well after the Meiji Restoration of 1868 and the subsequent industrialization of the country. Then it was too late to plan a grid of roads, for most of the main cities were all laid out. The narrow, crooked lanes previously used for foot traffic were the “boulevards.”

Even after World War II, and Japan’s rapid reconstruction, there was no adequate road program—just more cars, more trucks, more motorcycles, clogging up the twisty, bumpy roads in gigantic jams. The congestion is often so bad, and the evasive action taken to avoid it so frantic, that ordinarily mildmannered, polite Japanese take to screaming “bakayaro!” (“Yew stupid s.o.b.!!”) at one another. In many traffic situations, the law is completely ignored. Dump trucks roar along at 50 miles an hour in downtown Tokyo, and taxis go even faster, since cabbies live by the mileage they chalk up. There is a grudge match drag race away from every stoplight, as drivers jockey for position more desperately than Novices at Daytona. Bicycles weave through the paralyzed protozoan mass of vehicles, the riders balancing trays and bowls of rice, noodles, and other fishy delicacies in one hand. Ten hours a day, seven days a week, on every highway and byway of the nation—it is a metal madhouse.

Enter the Shirobai\ He’ll swoop down on a speeding daampu truck, and haul him in for a hundred dollar fine. He’ll nab some young dude in a Datsun sports car, wildly swinging through traffic on the meager freeways, and send him back to the subways, minus license. He’ll be on the scene of an accident in a flash, all reports and directions—and orders, orders, orders. But his job is, quite frankly, an impossible one. In the giant Suicide Circus of Tokyo traffic, he and his comrades, and the few patrol cars running about, are supposed to maintain law and order in a city of 11 million people. And there are only 714 of them. In all Japan, there are only 3000 motorcycle policemen; thus, the chances of being nabbed are really pretty slim.

The motorcycle patrol corps has actually been around for some time. It was organized before World War II in Tokyo. At that time they rode flaming red motorcycles, and thus were called akabai, from akai, which means “red.” Their mounts were rather startling: Rikuos, side-valve V-twins, no rear suspension, fish-tail exhaust and mud-flaps. They bore a striking resemblance to a certain American make of the same era. Each machine carried a little metal toolbox on the rear, and a sign reading, “Don’t cross the yellow line!”

The riders wore the same drab blue uniforms that regular patrolmen wore. They also wore white helmets of the paper mache variety, which were useful only for keeping their hair in place.

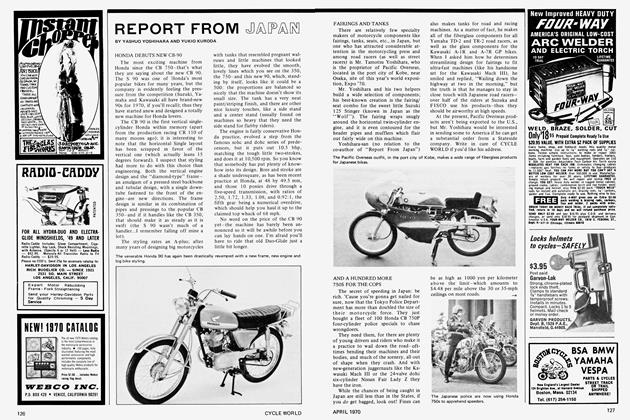

In the late 1950s, the patrol force graduated to more sophisticated machinery-big Honda and Meguro Twins (mainly the latter). The Meguro was a work horse, closely patterned after an early British motorcycle (complete with some of the charming defects the limey bike incorporated). When the company collapsed it was bought by Kawasaki; they carefully redesigned the Twin, sending the bugs packing with more strength and reliability than before. It now is sold with the rest of their line.

Both the Kawasakis and Hondas of today’s policemen are equipped with a hefty siren, lights, and (sometimes) a two-way radio to keep in touch with headquarters.

The machines, and the uniforms of riders, were coated with a special luminescent paint at one time—the idea was that this would make both more visible at night. You know—“Hey, what’s that glowing in the dark over there?”

“Either a UFO or a cop...”

This special attempt to cope with the extra dangers of night riding emphasized the rigorous nature of the shirobai patrolmen.

Theirs is a special assignment, and they are a very select crew. All are officers who have served at least two or three years at the station house, or at the little posts called “police boxes” located at main intersections throughout Japanese cities! Those who pass a tough physical test are then given the opportunity to try out for the motorcycle corps. They must be young, and a previous interest in motorcycling helps, too. They have to go through a special training course, which stresses their role in crime prevention. These patrolmen don’t hide behind billboards or in alleys. They station themselves ostentatiously on main roads where passing motorists are sure to spot them and ease off a bit on the speed. Their deterrent value is meant to lower Japan’s wicked accident rate.

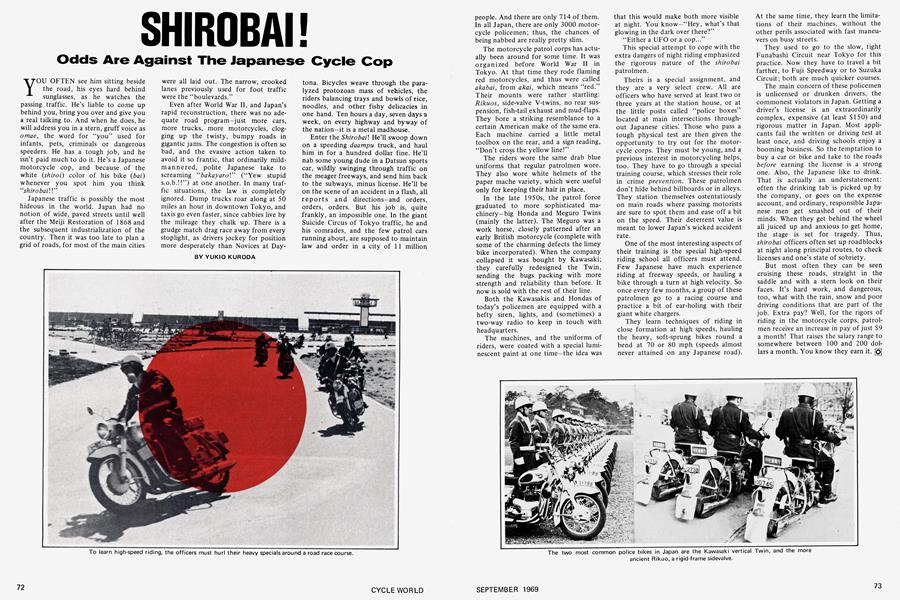

One of the most interesting aspects of their training is the special high-speed riding school all officers must attend. Few Japanese have much experience riding at freeway speeds, or hauling a bike through a turn at high velocity. So once every few months, a group of these patrolmen go to a racing course and practice a bit of ear-holing with their giant white chargers.

They learn techniques of riding in close formation at high speeds, hauling the heavy, soft-sprung bikes round a bend at 70 or 80 mph (speeds almost never attained on any Japanese road). At the same time, they learn the limitations of their machines, without the other perils associated with fast maneuvers on busy streets.

They used to go to the slow, tight Funabashi Circuit near Tokyo for this practice. Now they have to travel a bit farther, to Fuji Speedway or to Suzuka Circuit; both are much quicker courses.

The main concern of these policemen is unlicensed or drunken drivers, the commonest violators in Japan. Getting a driver’s license is an extraordinarily complex, expensive (at least $150) and rigorous matter in Japan. Most applicants fail the written or driving test at least once, and driving schools enjoy a booming business. So the temptation to buy a car or bike and take to the roads before earning the license is a strong one. Also, the Japanese like to drink. That is actually an understatement: often the drinking tab is picked up by the company, or goes on the expense account, and ordinary, responsible Japanese men get smashed out of their minds. When they get behind the wheel all juiced up and anxious to get home, the stage is set for tragedy. Thus, shirobai officers often set up roadblocks at night along principal routes, to check licenses and one’s state of sobriety.

But most often they can be seen cruising these roads, straight in the saddle and with a stern look on their faces. It’s hard work, and dangerous, too, what with the rain, snow and poor driving conditions that are part of the job. Extra pay? Well, for the rigors of riding in the motorcycle corps, patrolmen receive an increase in pay of just $9 a month! That raises the salary range to somewhere between 100 and 200 dollars a month. You know they earn it. [o]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

September 1969 By Joe Parkhurst -

Departments

DepartmentsThe Scene

September 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

Departments

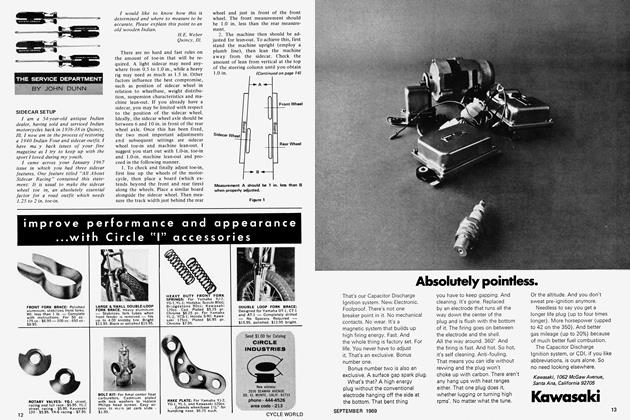

DepartmentsThe Service Department

September 1969 By John Dunn -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1969 -

Competition

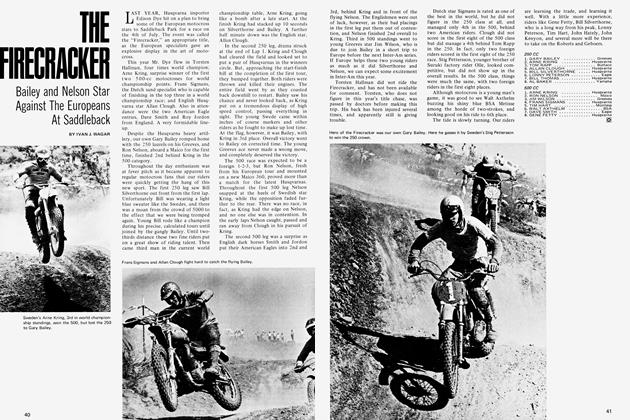

CompetitionThe Firecracker

September 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

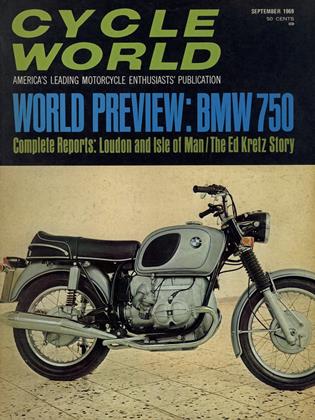

Preview

PreviewBmw 750-Cc R 75 Us

September 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar