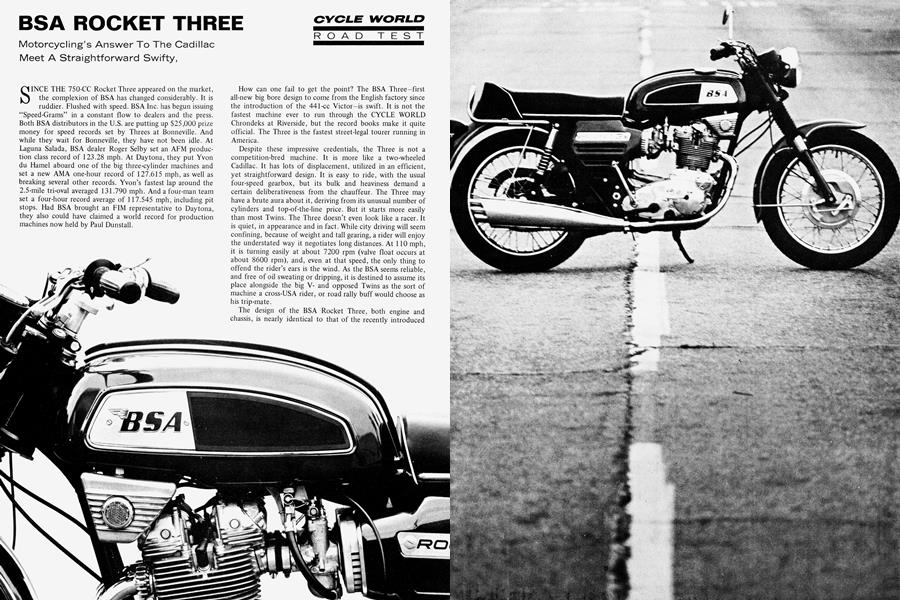

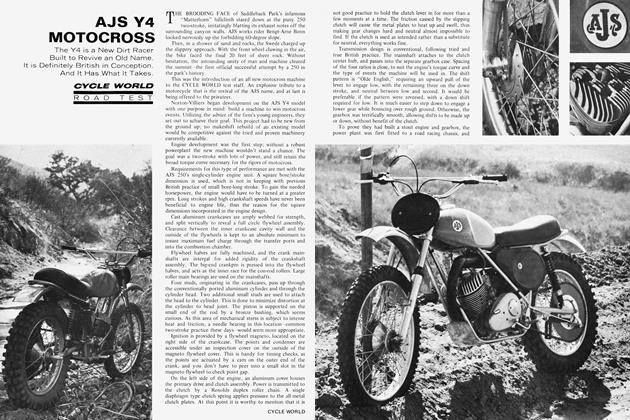

BSA ROCKET THREE

CYCLE WORLD ROAD TEST

Motorcycling’s Answer To The Cadillac Meet A Straightforward Swifty,

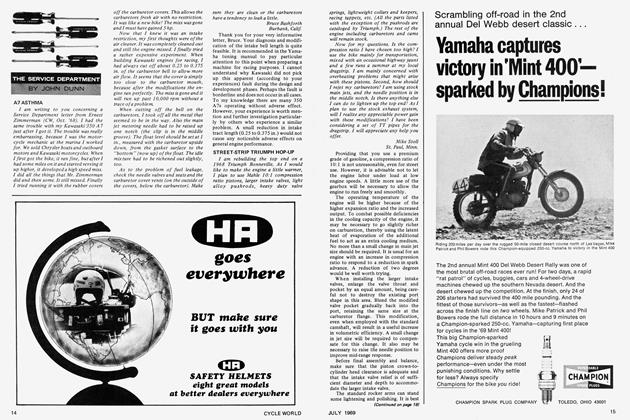

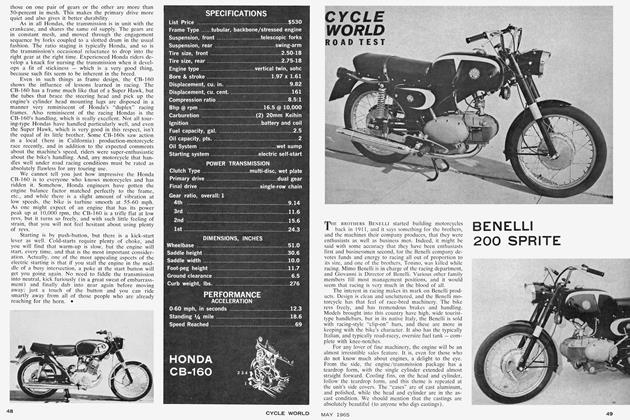

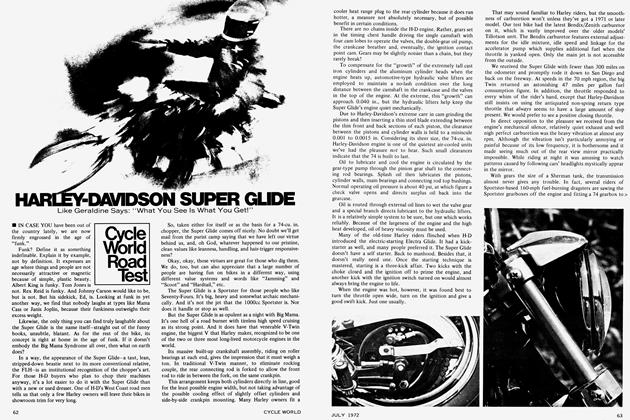

SINCE THE 750-CC Rocket Three appeared on the market, the complexion of BSA has changed considerably. It is ruddier. Flushed with speed. BSA Inc. has begun issuing “Speed-Grams” in a constant flow to dealers and the press. Both BSA distributors in the U.S. are putting up $25,000 prize money for speed records set by Threes at Bonneville. And while they wait for Bonneville, they have not been idle. At Laguna Salada, BSA dealer Roger Selby set an AFM production class record of 123.28 mph. At Daytona, they put Yvon du Hamel aboard one of the big three-cylinder machines and set a new AMA one-hour record of 127.615 mph, as well as breaking several other records. Yvon’s fastest lap around the 2.5-mile tri-oval averaged 131.790 mph. And a four-man team set a four-hour record average of 117.545 mph, including pit stops. Had BSA brought an FIM representative to Daytona, they also could have claimed a world record for production machines now held by Paul Dunstall.

How can one fail to get the point? The BSA Three—first all-new big bore design to come from the English factory since the introduction of the 441-cc Victor—is swift. It is not the fastest machine ever to run through the CYCLE WORLD Chrondeks at Riverside, but the record books make it quite official. The Three is the fastest street-legal tourer running in America.

Despite these impressive credentials, the Three is not a competition-bred machine. It is more like a two-wheeled Cadillac. It has lots of displacement, utilized in an efficient, yet straightforward design. It is easy to ride, with the usual four-speed gearbox, but its bulk and heaviness demand a certain deliberativeness from the chauffeur. The Three may have a brute aura about it, deriving from its unusual number of cylinders and top-of-the-line price. But it starts more easily than most Twins. The Three doesn’t even look like a racer. It is quiet, in appearance and in fact. While city driving will seem confining, because of weight and tall gearing, a rider will enjoy the understated way it negotiates long distances. At 110 mph, it is turning easily at about 7200 rpm (valve float occurs at about 8600 rpm), and, even at that speed, the only thing to offend the rider’s ears is the wind. As the BSA seems reliable, and free of oil sweating or dripping, it is destined to assume its place alongside the big Vand opposed Twins as the sort of machine a cross-USA rider, or road rally buff would choose as his trip-mate.

The design of the BSA Rocket Three, both engine and chassis, is nearly identical to that of the recently introduced Triumph Trident. It is an honest affinity, as BSA and Triumph are all but the same company. The choice of three vertical cylinders slung in-line across the frame is not an exercise in vanity or fantasy involving the magic of a design having more than two cylinders. It is the best possible compromise. The more cylinders you add-up to a point—the more efficient an engine may be. The combustion chambers may be kept small, allowing more instantaneous ignition of the fuel charge, yet—in relation to displacement—the potential for valve and port size increases.

The ideal in-line Three design, which has been adopted by BSA, utilizes a crankshaft with crankpins set 120 degrees apart. Out-of-balance forces cancel themselves out, resulting in smoother, and probably more long-lasting, operation. When the displacement is large, especially over 650-cc, the balance and breathing advantages of a Three are less of a luxury and more of a necessity.

The compromise part of the game is that BSA stopped at three cylinders, instead of producing a Four. Each extra cylinder adds more complexity, and adds to initial cost as well as maintenance cost. The Three enjoys all the innate good balance characteristics needed for its displacement, yet should cost less to produce than a Four. Further, an in-line Three still may be kept narrow enough to fit comfortably across a bike frame, and have reasonably low frontal area, while allowing enough space between cylinders for cooling. It may have a minimal number of plugs, ports, valve train parts, as well as a minimal crankshaft and camshaft length, to avoid flex. Fewer additional supporting bearings are needed to avoid such flex. In short, the Three is a living example of Maximin, a concept in game theory, which is a model for obtaining the maximum number of gains for the minimum number of losses.

The BSA has alloy heads, cylinder barrels (with Austenitic iron liners), and crankcases. It borrows its design and some components from the Triumph Twins, as well as bore/stroke configuration of the old Tiger 100. The crankshaft is forged with the crankpins in a single plane, then twisted to achieve the 120-degree crankpin layout and finally machined. It rides on a driving side ball bearing and a timing side roller bearing. The two central bearings are plain, as are the crankshaft big end bearings, the advantage being that a plain bearing will carry heavier loadings than a like-sized ball or roller bearing. The penalty of a plain bearing is that it produces more drag, and makes the job of lubrication extremely important. But, as the BSA is not basically a high-rpm engine, and will spend much of its time chugging around at low engine speed where engine loadings are highest, the plain bearings are the reliable and economical alternative.

Lubrication and oil cooling are important for another reason in a Three—the middle cylinder, which does not receive as much air cooling as the other two. Hence the dry sump system, of orthodox design, incorporates a 0.25-pint capacity oil cooler mounted underneath the front of the fuel tank. Oil, circulated 3.5 times as fast as in the 650 Twin, is fed by gravity from a tank to a double-gear pump, which has a greater capacity than the traditional plunger pump. One set of gears in the pump draws oil from the tank and delivers it under pressure past a non-return valve into the two center main bearings. The oil then flows through drillings in the crankshaft to the big-end bearing. Centrifugal force splashes the excess onto cylinder walls, piston undersides and wrist pins, and is collected in various wells to lubricate the intake and exhaust camshafts. Part of the oil pressure to the center mains bleeds off through small pipes to lubricate tappets and cam faces. The outer main bearings are splash fed. Oil draining to the sump goes to the scavenge side of the oil pump, passes to the oil cooler and returns to the tank, An unusual feature of the oil tank is that it has an easily accessible screw under the cap to adjust the rate of a drip feed rear chain oiler. The tank cap has a dip stick which doubles as a screwdriver for making the adjustment.

Three filters are incorporated in the lubrication system: the gauze tank filter, a crankcase filter accessible by removing a cap near the timing cover, and the usual sump filter integrated with the sump plate. The oil change period prescribed by the factory is long-40ÛÜ miles—indicating their reliance on the effectiveness of the filtering system and the hope that it will be cleaned at each oil change. Gearbox and primary chaincase each have a separate supply of oil.

Taking after the Triumph part of the BSA/Triumph combine, the valves are actuated by pushrods running between the cylinders from two camshafts located high in the block, one for intake, the other for exhaust. 'The valve head diameters—1.53 in. for the inlet, and 1.31 in. for the exhaust—are also the same as the current 500-cc Triumph. One wonders why the manufacturers didn’t choose an ohc engine, for a “new” design. In truth, they weren’t starting from scratch, and felt that borrowing from the pushrod designs already proven on the BSA and Triumph Twins would assure them the greatest chance of success. Development engineers Bert Hopwood and Doug Hele further note that an ohc setup is really necessary only if you’re going after all the horsepower you can get. As the Three’s output is now 62 bhp and may be stretched to an easy design limit of 75 bhp, both men feel that the pushrod setup offers more than enough power for a road bike.

The cam timing is “sporty.” Duration for both intake and exhaust cams is 294 degrees. But choke size of the three 27-mm Arnal concentric carburetors is moderate, and the engine is not at all fussy at low rpm. In practice, the power band does not become particularly lively until about 3500 rpm. It then buzzes freely past the 8000-rpm power peak until valve float commences at about 8600 rpm. The compression ratio is a modest 9.5:1, and, because starting effort is split between three cylinders, hardly any pressure is required on the kickstart lever. Starting drill is hardly a drill at all: tickle one or two of the carburetors and kick, without opening the throttle.

The BSA Three crankcase/gearbox unit is a variation on traditional British practice. The casting is in three sections. The central one extends rearward to include the gearbox, and the two outer crank chambers are split vertically from the center section. The primary drive and timing unit have separate covers. This practice leaves open the possibility of oil leaks from the four vertical splits. But oil leaking isn’t necessarily the rule with this arrangement. Of several BSAs sampled by CYCLE WORLD, only one showed a propensity for leaking.

Power from the engine to the gearbox input sprocket is transmitted by triplex chain. The four-gear transmission is basically a Bonneville design, and even feels the same as the Bonnie’s. But the clutch follows automotive practice to cope with automotive power; it is a Borg and Beck diaphragm spring single-plate dry clutch. A rubber-faced tensioner provides primary chain adjustment. Inside the clutch sprocket, a rubber-packed shock absorber unit smooths the power impulses. Gear changing is smooth, but stiff, and during high-rpm acceleration, upshifting from first to second requires a deliberate, firm scoop of the gear lever. Downshifting is accomplished quite rapidly.

The chassis is nothing out of the ordinary—single loop frame construction forking into a double cradle. A reinforcing tube is slung under the toptube. The Rocket handles well, especially considering its 495-lb. curb weight. The suspension is set up soft, for touring, so it tends to produce a mild, periodic “yoing” when cornering hard over less than perfect surfaces.

Another disadvantage for those riders with racer aspirations is the ease with which one may ground either side of the BSA when leaning hard. There is no problem leaning the bike hard, as the traction afforded by the front Dunlop K70 and the new 4.10-19 K81 “trigonic” is excellent. This rear tire, designed especially to cope with the Three’s power output, does exactly that. Even if you raise the revs to 8000, sit as far forward as possible and allow the clutch to snap home, it is impossible to get the tire to “burn” for more than a few feet. For drag racing, the K81 offers too much traction, and a noticeable improvement in e.t. may be achieved by putting a more conventional K70 on the back—which will allow the slippage necessary to keep the Three on its torque peak off the start. If you are running quarter-mile in the low to middle 13s, using a K81 rear, as we were, you will immediately drop into the high 12s and top 100 mph by switching to a K70 rear.

Slowing down is another matter. The brakes are the same size as those on the BSA Twins, which weigh much less. Such brakes on a Twin would give us great confidence. The same units on the BSA Three leave us not quite so trusting, although the stopping action at normal speeds is good, with fairly positive feel.

Should the exhaust pipes become blue at their balancing junctions, it apparently is no cause for alarm. It happened to every example tested. The rear chain tends to rattle against its guard when accelerating from low rpm with two in the saddle, but the phenomenon soon disappears. And while complaining, a quick jab at those chi-chi looking triple-stinger mufflers is in order. Hope they change next year. On the other hand, leave them and maybe they’ll become a tradition.

As befits a king-sized tourer, the lighting system is excellent and the twin horns are loud. The electrical system consists of a crankshaft-driven alternator with 140-watt capacity, 12-volt battery, triple contact breaker and three coils.

Everything about the bike speaks of long distance. Very little irritation from noise or vibration. Wide, comfortable seat, and, in spite of extra engine width, an excellent sitting position. With lower gearing, the Three would make an excellent sidecar machine. All a rider can think when he sets out is, “Just wait until I get out of town!”

BSA ROCKET THREE

$1765