THE SCENE

IVAN J. WAGAR

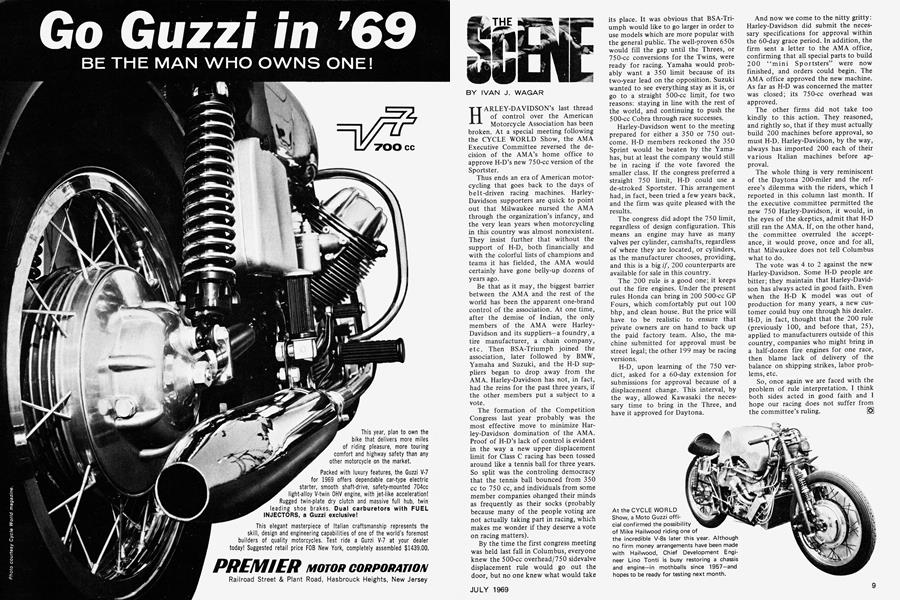

HARLEY-DAVIDSON’S last thread of control over the American Motorcycle Association has been broken. At a special meeting following the CYCLE WORLD Show, the AMA Executive Committee reversed the decision of the AMA’s home office to approve H-D’s new 750-cc version of the Sportster.

Thus ends an era of American motorcycling that goes back to the days of belt-driven racing machines. HarleyDavidson supporters are quick to point out that Milwaukee nursed the AMA through the organization’s infancy, and the very lean years when motorcycling in this country was almost nonexistent. They insist further that without the support of H-D, both financially and with the colorful lists of champions and teams it has fielded, the AMA would certainly have gone belly-up dozens of years ago.

Be that as it may, the biggest barrier between the AMA and the rest of the world has been the apparent one-brand control of the association. At one time, after the demise of Indian, the only members of the AMA were HarleyDavidson and its suppliers—a foundry, a tire manufacturer, a chain company, etc. Then BSA-Triumph joined the association, later followed by BMW, Yamaha and Suzuki, and the H-D suppliers began to drop away from the AMA. Harley-Davidson has not, in fact, had the reins for the past three years, if the other members put a subject to a vote.

The formation of the Competition Congress last year probably was the most effective move to minimize Harley-Davidson domination of the AMA. Proof of H-D’s lack of control is evident in the way a new upper displacement limit for Class C racing has been tossed around like a tennis ball for three years. So split was the controling democracy that the tennis ball bounced from 350 cc to 750 cc, and individuals from some member companies ohanged their minds as frequently as their socks (probably because many of the people voting are not actually taking part in racing, which makes me wonder if they deserve a vote on racing matters).

By the time the first congress meeting was held last fall in Columbus, everyone knew the 500-cc overhead/750 sidevalve displacement rule would go out the door, but no one knew what would take its place. It was obvious that BSA-Triumph would like to go larger in order to use models which are more popular with the general public. The well-proven 650s would fill the gap until the Threes, or 750-cc conversions for the Twins, were ready for racing. Yamaha would probably want a 350 limit because of its two-year lead on the opposition. Suzuki wanted to see everything stay as it is, or go to a straight 500-cc limit, for two reasons: staying in line with the rest of the world, and continuing to push the 500-cc Cobra through race successes.

Harley-Davidson went to the meeting prepared for either a 350 or 750 outcome. H-D members reckoned the 350 Sprint would be beaten by the Yamahas, but at least the company would still be in racing if the vote favored the smaller class. If the congress preferred a straight 750 limit, H-D could use a de-stroked Sportster. This arrangement had, in fact, been tried a few years back, and the firm was quite pleased with the results.

The congress did adopt the 750 limit, regardless of design configuration. This means an engine may have as many valves per cylinder, camshafts, regardless of where they are located, or cylinders, as the manufacturer chooses, providing, and this is a big if, 200 counterparts are available for sale in this country.

The 200 rule is a good one; it keeps out the fire engines. Under the present rules Honda can bring in 200 500-cc GP Fours, which comfortably put out 100 bhp, and clean house. But the price will have to be realistic to ensure that private owners are on hand to back up the paid factory team. Also, the machine submitted for approval must be street legal; the other 199 may be racing versions.

H-D, upon learning of the 750 verdict, asked for a 60-day extension for submissions for approval because of a displacement change. This interval, by the way, allowed Kawasaki the necessary time to bring in the Three, and have it approved for Daytona.

And now we come to the nitty gritty: Harley-Davidson did submit the necessary specifications for approval within the 60-day grace period. In addition, the firm sent a letter to the AMA office, confirming that all special parts to build 200 “mini Sportsters” were now finished, and orders could begin. The AMA office approved the new machine. As far as H-D was concerned the matter was closed; its 750-cc overhead was approved.

The other firms did not take too kindly to this action. They reasoned, and rightly so, that if they must actually build 200 machines before approval, so must H-D. Harley-Davidson, by the way, always has imported 200 each of their various Italian machines before approval.

The whole thing is very reminiscent of the Daytona 200-miler and the referee’s dilemma with the riders, which I reported in this column last month. If the executive committee permitted the new 750 Harley-Davidson, it would, in the eyes of the skeptics, admit that H-D still ran the AMA. If, on the other hand, the committee overruled the acceptance, it would prove, once and for all, that Milwaukee does not tell Columbus what to do.

The vote was 4 to 2 against the new Harley-Davidson. Some H-D people are bitter; they maintain that Harley-Davidson has always acted in good faith. Even when the H-D K model was out of production for many years, a new customer could buy one through his dealer. H-D, in fact, thought that the 200 rule (previously 100, and before that, 25), applied to manufacturers outside of this country, companies who might bring in a half-dozen fire engines for one race, then blame lack of delivery of the balance on shipping strikes, labor problems, etc.

So, once again we are faced with the problem of rule interpretation. I think both sides acted in good faith and I hope our racing does not suffer from the committee’s ruling. M