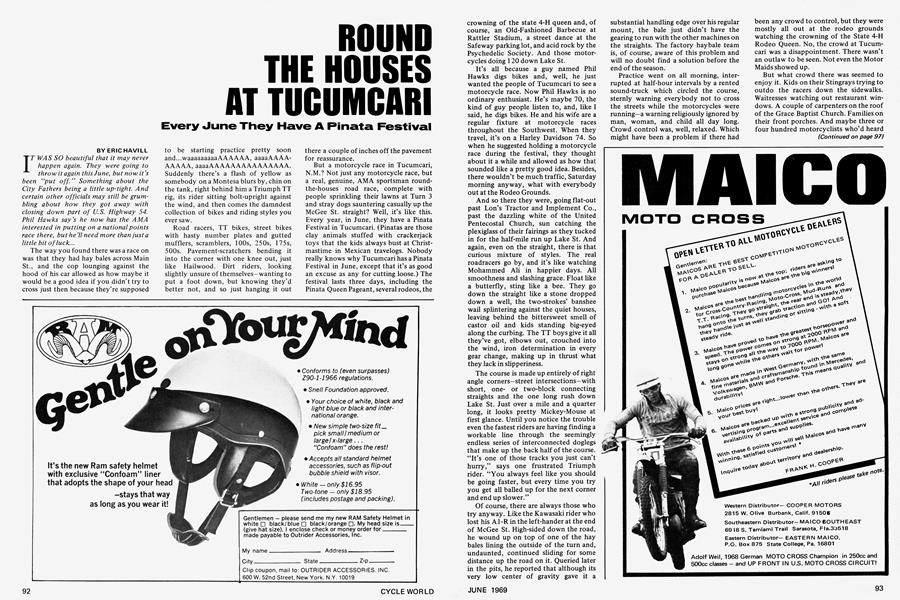

ROUND THE HOUSES AT TUCUMCARI

Every June They Have A Pinata Festival

ERIC HAVILL

IT WAS SO beautiful that it may never happen again. They were going to throw it again this June, but now it’s been “put off.” Something about the City Fathers being a little up-tight. And certain other officials may still be grumbling about how they got away with closing down part of U.S. Highway 54. Phil Hawks say’s he now has the AMA interested in putting on a national points race there, but he’ll need more than just a little bit of luck...

The way you found there was a race on was that they had hay bales across Main St., and the cop lounging against the hood of his car allowed as how maybe it would be a good idea if you didn’t try to cross just then because they’re supposed to be starting practice pretty soon and...waaaaaaaaaAAAAAA, aaaaAAAAAAAAA, aaaaAAAAAAAAAAAAAAA. Suddenly there’s a flash of yellow as somebody on a Montesa blurs by, chin on the tank, right behind him a Triumph TT rig, its rider sitting bolt-upright against the wind, and then comes the damndest collection of bikes and riding styles you ever saw.

Road racers, TT bikes, street bikes with hasty number plates and gutted mufflers, scramblers, 100s, 250s, 175s, 500s. Pavement-scratchers bending it into the corner with one knee out, just like Hailwood. Dirt riders, looking slightly unsure of themselves—wanting to put a foot down, but knowing they’d better not, and so just hanging it out there a couple of inches off the pavement for reassurance.

But a motorcycle race in Tucumcari, N.M.? Not just any motorcycle race, but a real, genuine, AMA sportsman roundthe-houses road race, complete with people sprinkling their lawns at Turn 3 and stray dogs sauntering casually up the McGee St. straight? Well, it’s like this. Every year, in June, they have a Piñata Festival in Tucumcari. (Piñatas are those clay animals stuffed with crackerjack toys that the kids always bust at Christmastime in Mexican travelogs. Nobody really knows why Tucumcari has a Piñata Festival in June, except that it’s as good an excuse as any for cutting loose.) The festival lasts three days, including the Piñata Queen Pageant, several rodeos, the crowning of the state 4-H queen and, of course, an Old-Fashioned Barbecue at Rattler Stadium, a street dance at the Safeway parking lot, and acid rock by the Psychedelic Society. And those motorcycles doing 120 down Lake St.

It’s all because a guy named Phil Hawks digs bikes and, well, he just wanted the people of Tucumcari to see a motorcycle race. Now Phil Hawks is no ordinary enthusiast. He’s maybe 70, the kind of guy people listen to, and, like I said, he digs bikes. He and his wife are a regular fixture at motorcycle races throughout the Southwest. When they travel, it’s on a Harley Davidson 74. So when he suggested holding a motorcycle race during the festival, they thought about it a while and allowed as how that sounded like a pretty good idea. Besides, there wouldn’t be much traffic, Saturday morning anyway, what with everybody out at the Rodeo Grounds.

And so there they were, going flat-out past Lon’s Tractor and Implement Co., past the dazzling white of the United Pentecostal Church, sun catching the plexiglass of their fairings as they tucked in for the half-mile run up Lake St. And again, even on the straight, there is that curious mixture of styles. The real roadracers go by, and it’s like watching Mohammed Ali in happier days. All smoothness and slashing grace. Float like a butterfly, sting like a bee. They go down the straight like a stone dropped down a well, the two-strokes’ banshee wail splintering against the quiet houses, leaving behind the bittersweet smell of castor oil and kids standing big-eyed along the curbing. The TT boys give it all they’ve got, elbows out, crouched into the wind, iron determination in every gear change, making up in thrust what they lack in slipperiness.

The course is made up entirely of right angle corners—street intersections—with short, oneor two-block connecting straights and the one long rush down Lake St. Just over a mile and a quarter long, it looks pretty Mickey-Mouse at first glance. Until you notice the trouble even the fastest riders are having finding a workable line through the seemingly endless series of interconnected doglegs that make up the back half of the course. “It’s one of those tracks you just can’t hurry,” says one frustrated Triumph rider. “You always feel like you should be going faster, but every time you try you get all balled up for the next corner and end up slower.”

Of course, there are always those who try anyway. Like the Kawasaki rider who lost his Al-R in the left-hander at the end of McGee St. High-sided down the road, he wound up on top of one of the hay bales lining the outside of the turn and, undaunted, continued sliding for some distance up the road on it. Queried later in the pits, he reported that although its very low center of gravity gave it a substantial handling edge over his regular mount, the bale just didn’t have the gearing to run with the other machines on the straights. The factory haybale team is, of course, aware of this problem and will no doubt find a solution before the end of the season.

Practice went on all morning, interrupted at half-hour intervals by a rented sound-truck which circled the course, sternly warning everybody not to cross the streets while the motorcycles were running—a warning religiously ignored by man, woman, and child all day long. Crowd control was, well, relaxed. Which might have been a problem if there had been any crowd to control, but they were mostly all out at the rodeo grounds watching the crowning of the State 4-H Rodeo Queen. No, the crowd at Tucumcari was a disappointment. There wasn’t an outlaw to be seen. Not even the Motor Maids showed up.

But what crowd there was seemed to enjoy it. Kids on their Stingrays trying to outdo the racers down the sidewalks. Waitresses watching out restaurant windows. A couple of carpenters on the roof of the Grace Baptist Church. Families on their front porches. And maybe three or four hundred motorcyclists who’d heard there was a race on and rode up from Albuquerque or West Texas or even Colorado. They sat on the low stone walls of the town plaza, talking and drinking beer with the locals and ranchers in for the festival.

(Continued on page 97)

Continued from page 93

“They sure seem small.”

“Yeah, those are the 250s.”

“I had a Harley right after the war’d make them seem just like toys. Course I guess it probably wasn’t so fast, but that sure was a big old motor.”

Practice ends at noon and everybody makes for the nearest shade. Even the pits seem strangely deserted.

It’s still hot at 2:30 when they line up for the 100-cc heat. Only nine bikes show, and it looks like you might better have stayed inside the Youth Center and had another orange soda, because who wants to watch a bunch of tiddlers playing follow-the-leader, right? Wrong. Oh, they take awhile getting down the straight all right, but they make up for it in the serpentine kinks along the back half of the course. The riders are mostly kids—16 or 17 years old—and they have yet to realize they’re not immortal. Right, left, right, left, they go through the corners like they never heard of the laws of physics. And the thing is, they never shut off, because if they do it takes half a lap to get up to speed again and, besides, it’s frustrating as hell.

The 175 heat is a walkaway for Dwight Hunter, riding a Bultaco. With starspangled blue leathers and white boxing shoes, Hunter has no choice but to win it. Can you imagine what 4th or 5th would do to his image? It hardly bears thinking about.

Then there was the 250 heat. For the first couple of laps it looked like another parade, led by J.C. Klusmeyer’s superslick Montesa road racer. Then, out of nowhere, there was Roy Valasquez, Yamaha TD1-B, right on the Montesa’s tail. For the next eight laps the two of them put on a race. Valasquez tried everything he knew to get past, including bouncing off the curbs, but Klusmeyer never made a mistake. Finally, after a next-to-the-last-lap excursion across someone’s front lawn that cost him a bent rim and decimated the owner’s tulip patch, Valasquez lost his bid and Klusmeyer breezed home, an easy winner.

After that, the 500-cc heat should have been an anticlimax. Instead, it was more of the same. This time it was between the Honda 450s of Don Parker and Charlie Kelln. Nobody else was even close. The two of them would go through the corners elbow-to-elbow, no more than a few feet separating them down the long straight, then side-by-side again through the turns, laying the bikes right down to the cases. Beautiful. And then Kelln got on it a little too soon leaving the plaza corner on the last lap and dropped it. He got going again in time to salvage 2nd, but Parker was long gone. And by now, even the little old ladies tending their grandchildren on the plaza were getting interested. “I like watching them, only they make so much noise. It doesn’t seem as if they have to be quite so loud, but the colors are nice.”

The main events were plagued by retirements, but, still, there was some good racing. Stanley Johnson outlasted some and outrode some to put his Twin-Jet into 2nd place at the end of the combined 100/175-cc main, not far behind Dwight Hunter’s 175 Bultaco. In the combined 250/500-cc final, Don Parker dropped out, which ought to have given the race to Kelln’s Honda 450 on a platter, except J.C. Klusmeyer had already put half the length of the straight between his Montesa and everybody else and Kelln had to make do with 2nd.

And then, suddenly it’s all over. They put the bikes back on the trailer and some old guy with a flatbed truck starts around the course to pick up his hay bales. Walking back to your car, you’re almost zapped by a couple of kids on Schwinn Stingrays. They flash by, pedal like mad down to the corner of the sidewalk, stand on the brakes and sliiiiii...iiiide. [Ö]

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Round Up

June 1969 By Joe Parkhurst -

The Scene

June 1969 By Ivan J. Wagar -

The Service Department

June 1969 By John Dunn -

Letters

LettersLetters

June 1969 -

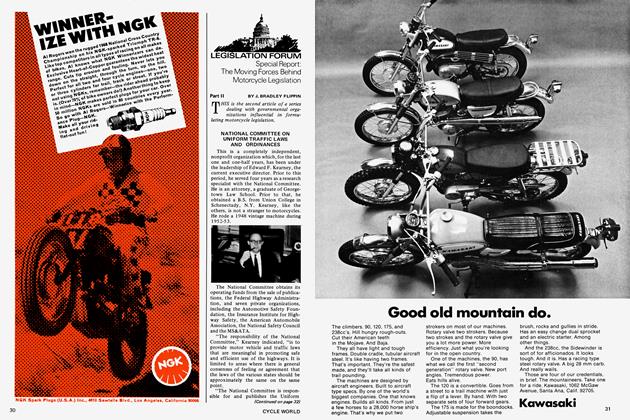

Legislation Forum

Legislation ForumSpecial Report: the Moving Forces Behind Motorcycle Legislation

June 1969 By J. Bradley Flippin -

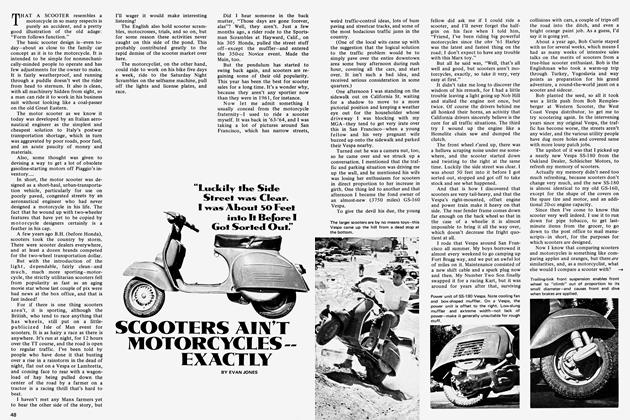

Offshoot Dept.

Offshoot Dept.Scooters Ain't Motorcycles-- Exactly

June 1969 By Evan Jones