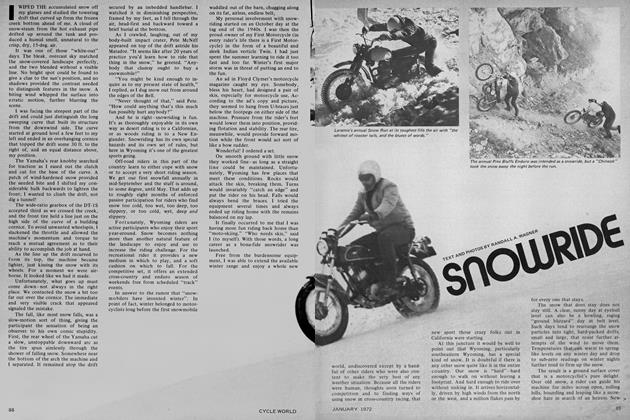

OREGON TRAIL

A Triumph Cub Tries The Greatest-Ever Enduro

RANDALL A. WAGNER

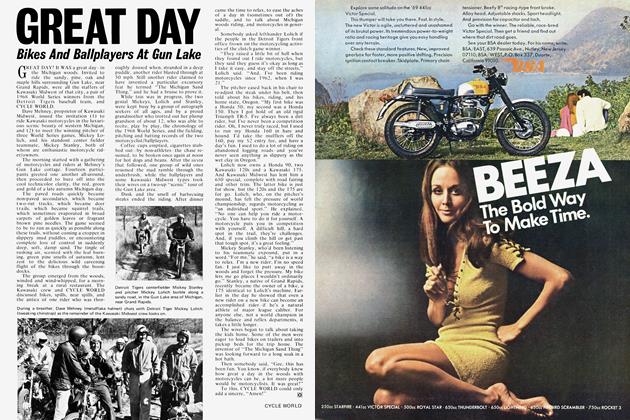

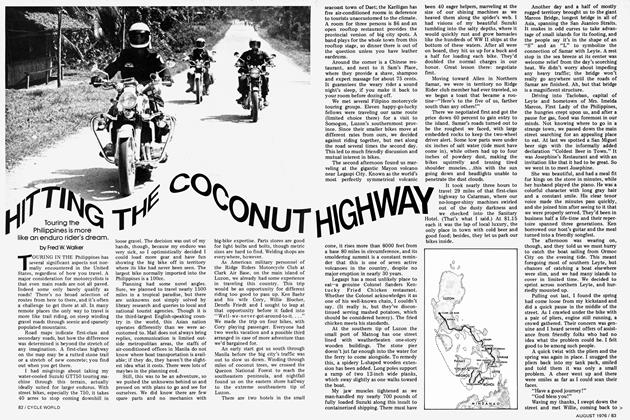

IT HAD TO BE the greatest enduro ever! It started on the banks of the Missouri River with spring's first thaw, and ended, for those who lived through it, on the Pacific shores during early winter snowstorms. Participants came from all walks of life-farmers, prospectors, members of religious move ments, businessmen, housewives, badmen, soldiers and speculators.

For more than 20 years, they annually attempted the one-way trip in fourwheeled, 2-oxpower desert sleds called Conestoga wagons. Entries in a single year’s enduro could number as high as 40,000 men, women and children. When it was finally completed, nine graves would line each mile of the route.

The route was called the Oregon Trail. The time was the mid-1800s. In the pages of history, the Oregon Trail is only a footnote, yet it existed long enough to expand America into a land that had been British and Spanish, and civilization to a Country that was wild. Along its dusty, rugged path came fur trappers to the Rocky Mountains, emigrant farmers to Oregon, 49ers to California and Mormon Pioneers to the Valley of the Great Salt Lake.

At the summit, where the westbound traveler left Nebraska Territory and entered Oregon Territory, was located the key to the trail, the South Pass through the Rocky Mountains. This was the only place on the continent that offered a wagon road to the northwest. It was a high, windswept plain crossing the continental divide between the snowcapped mountains to the north and the canyonlands of the Green and Colorado Rivers to the south.

Years later, after railroads had made the Oregon Trail obsolete, the country surrounding this Pass for hundreds of miles in each direction was to become a state called Wyoming. That’s where I come into the picture. I live there.

I knew of the trail while I was growing up in Lander, and rode in its ruts, from time to time, on horseback, on a delightfully green Cushman Motorscooter, on an equally green Indian Warrior and, finally, on an exceptionally black Matchless. That was in the late 1940s and early 50s. I rode for the fun of riding and knew not where the ruts came from, where they went or who made them. They crossed tough country and offered considerable cycling challenge and, then, that was enough.

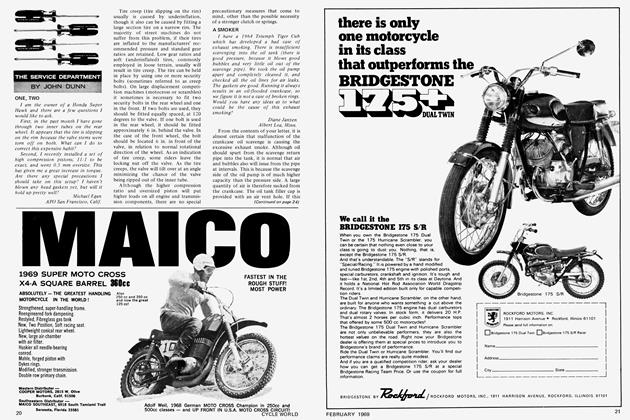

Times have changed. Now I’m riding the ruts again, this time on a geareddown Triumph Mountain Cub, from one end of the state to the other. My purpose is now serious, but every bit as enjoyable. My selection of motorcycle transportation was based on practical reasons that fail to limit the fun of riding. But I’ll start at the beginning.

About two years ago, the Wyoming Legislature gathered in Cheyenne for one of its every-other-year sessions and accomplished, among other things, the merger of several small state agencies into a new unit of government called the Wyoming Recreation Commission. One of the responsibilities assigned the new agency was the research, development and management of all state historic and archaeological sites.

With such high motives as “a chance to do something new and important for Wyoming” in mind, I left a good photographer’s job with the state’s Game and Fish Department, and joined the staff of the infant Commission. Director Charles R. Rodermel’s instructions were to the point.

“The Oregon Trail is Wyoming’s major historic feature,” he said. “Few people know what it is. Few people know where it is. Make a movie about it so they will.”

Chuck and I had worked together before, and we knew how to communicate. Noting the blank look on my face he added, “See Paul Henerson.”

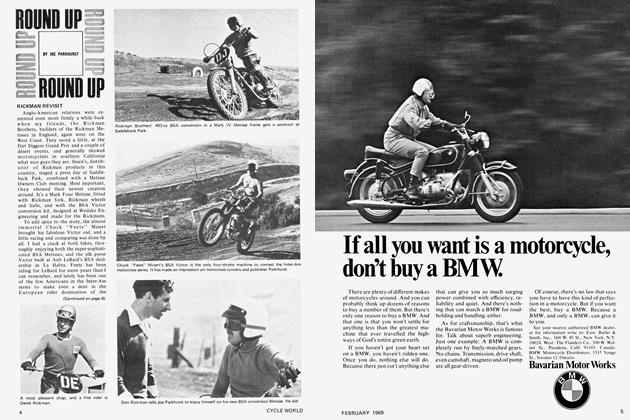

Paul is in his 70s and has spent the better part of those years doing Oregon Trail research—walking the ruts, mapping, reading a vast collection of pioneer diaries, corresponding with people whose grandparents and great grandparents made the trip. He knows as much about it as any man.

He is retired now, having worked on the Burlington Railroad and, later, as Historian for the State of Wyoming. He liked Chuck’s idea of an Oregon Trail movie.

“Been trying to get something like that done for 30 years,” he said. “You bet I’ll help. When do we start?”

It was then the middle of winter, which was the only reason I’d found Paul at home. Whenever the fabled Wyoming wind drops below 30 knots, and the temperature rises above -20 F, he can only be found somewhere along the Trail tracing out another branch.

“This spring,” I said. “Soon as it warms up.”

Paul figured he could wait until May—that’s spring in Wyoming—but no longer. “We’ll start at Fort Laramie and end at Fort Bridger,” he said. “Have you got a motorcycle?”

The question was a total surprise. “Trail bike,” I managed.

“Bring it. It’s the only way to really travel the Trail. Don’t ride any more myself, but wore out a few when I did.” So it was that early May found us, Conestoga Cub in tow, headed west out of Torrington for the famous old fur traders post known originally as Fort

John, then Fort William and finally, with the advent of the military on the western frontier, Fort Laramie. Before we got there, Paul called a halt, helped unload the Cub and pointed me south.

“Ride a mile or so and see what you find,” he said.

What he had in mind was soon evident-even to a rank amateur trail hound. Within the mile of sagebrush prairie I had crossed no less than five distinct parallel sets of trail ruts, untouched since the day they were last used some 100 years ago. I followed the middle set west and soon came to a high bluff overlooking the Fort and the Laramie River. The other four branches converged with the ruts I had followed making one track.

Excited at my discovery, I stood on the pegs and headed back to report with the Cub roaring, bouncing, jumping and speeding as well as a Cub can roar, bounce, jump and speed.

“I found five sets of ruts that all come together on the bluff over the Fort!” I yelled as the Cub slid to a halt.

“You missed one,” said Paul stepping out of the dust. “A sixth track drops off the bluff north of the others. Look closer next time.”

That was my first lesson. Two others followed as we loaded the bike.

“The Oregon Trail is not a single track west,” said Paul. “It’s really a series of landmarks and campgrounds that the emigrants used to get to their destination. If grass or water became a problem along the main trail, the wagonmaster would lead the train onto one of several branches.”

Paul explained that many other factors dictated the route a particular train would use at a particular time, listing such things as weather, the flood stage of rivers, the time of year and the personal preference of different guides.

“There are places where the branches are as much as 20 miles apart,” he said.

He also pointed out that Wyoming’s low population had done much to preserve the trail ruts. It is one of the Nation’s largest states but claims less than 400,000 citizens. The land occupied by the Trail, high, dry bench country mostly, hasn’t yet become necessary for human use.

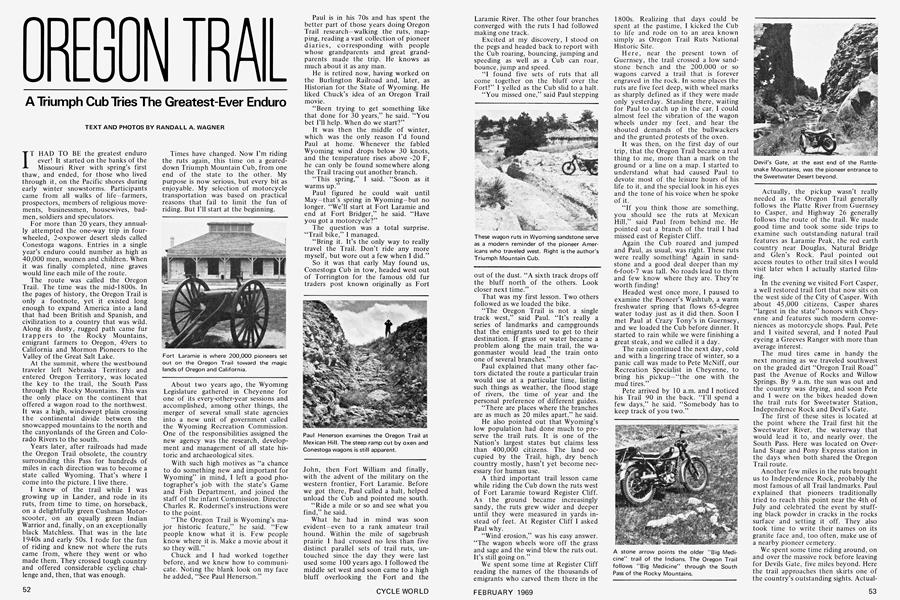

A third important trail lesson came while riding the Cub down the ruts west of Fort Laramie toward Register Cliff. As the ground became increasingly sandy, the ruts grew wider and deeper until they were measured in yards instead of feet. At Register Cliff I asked Paul why.

“Wind erosion,” was his easy answer. “The wagon wheels wore off the grass and sage and the wind blew the ruts out. It’s still going on.”

We spent some time at Register Cliff reading the names of the thousands of emigrants who carved them there in the 1800s. Realizing that days could be spent at the pastime, I kicked the Cub to life and rode on to an area known simply as Oregon Trail Ruts National Historic Site.

Here, near the present town of Guernsey, the trail crossed a low sandstone bench and the 200,000 or so wagons carved a trail that is forever engraved in the rock. In some places the ruts are five feet deep, with wheel marks as sharply defined as if they were made only yesterday. Standing there, waiting for Paul to catch up in the car, I could almost feel the vibration of the wagon wheels under my feet, and hear the shouted demands of the bullwackers and the grunted protests of the oxen.

It was then, on the first day of our trip, that the Oregon Trail became a real thing to me, more than a mark on the ground or a line on a map. I started to understand what had caused Paul to devote most of the leisure hours of his life to it, and the special look in his eyes and the tone of his voice when he spoke of it.

“If you think those are something, you should see the ruts at Mexican Hill,” said Paul from behind me. He pointed out a branch of the trail I had missed east of Register Cliff.

Again the Cub roared and jumped and Paul, as usual, was right. These ruts were really something! Again in sandstone and a good deal deeper than my 6-foot-7 was tall. No roads lead to them and few know where they are. They’re worth finding!

Headed west once more, I paused to examine the Pioneer’s Washtub, a warm freshwater spring that flows 65-degree water today just as it did then. Soon I met Paul at Crazy Tony’s in Guernsey, and we loaded the Cub before dinner. It started to rain while we were finishing a great steak, and we called it a day.

The rain continued the next day, cold and with a lingering trace of winter, so a panic call was made to Pete McNiff, our Recreation Specialist in Cheyenne, to bring his pickup-“the one with the mud tires.”

Pete arrived by 10 a.m. and I noticed his Trail 90 in the back. “I’ll spend a few days,” he said. “Somebody has to keep track of you two.”

Actually, the pickup wasn’t really needed as the Oregon Trail generally follows the Platte River from Guernsey to Casper, and Highway 26 generally follows the route of the trail. We made good time and took some side trips to examine such outstanding natural trail features as Laramie Peak, the red earth country near Douglas, Natural Bridge and Glen’s Rock. Paul pointed out access routes to other trail sites I would visit later when I actually started filming.

In the evening we visited Fort Casper, a well restored trail fort that now sits on the west side of the City of Casper. With about 45,000 citizens, Casper shares “largest in the state” honors with Cheyenne and features such modern conveniences as motorcycle shops. Paul, Pete and I visited several, and 1 noted Paul eyeing a Greeves Ranger with more than average interest.

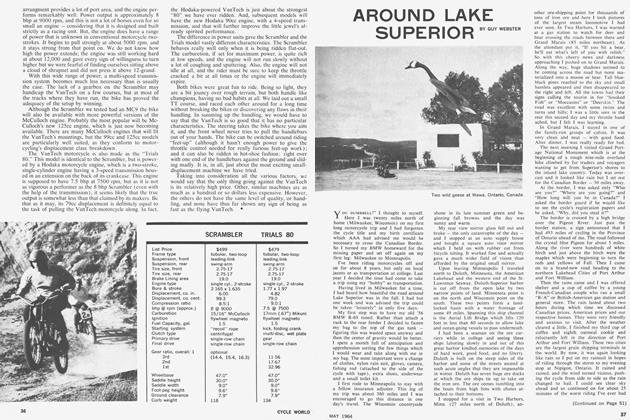

The mud tires came in handy the next morning as we traveled southwest on the graded dirt “Oregon Trail Road” past the Avenue of Rocks and Willow Springs. By 9 a.m. the sun was out and the country was drying, and soon Pete and I were on the bikes headed down the trail ruts for Sweetwater Station, Independence Rock and Devil’s Gate.

The first of these sites is located at the point where the Trail first hit the Sweetwater River, the waterway that would lead it to, and nearly over, the South Pass. Here was located on Overland Stage and Pony Express station in the days when both shared the Oregon Trail route.

Another few miles in the ruts brought us to Independence Rock, probably the most famous of all Trail landmarks. Paul explained that pioneers traditionally tried to reach this point near the 4th of July and celebrated the event by stuffing black powder in cracks in the rocks surface and setting it off. They also took time to write their names on its granite face and, too often, make use of a nearby pioneer cemetery.

We spent some time riding around, on and over the massive rock before leaving for Devils Gate, five miles beyond. Here the trail approaches then skirts one of the country’s outstanding sights. Actually, Devil’s Gate is a vertical split in the east end of the rugged granite Rattlesnake Mountains, with sheer sides from summit to river channel. Its sides are hundreds of feet high and so close together it appears that a man could jump across. The river course is so direct that a straight-through view is the traveler’s reward.

Devil’s Gate marks the start of the Sweetwater Desert, 100 miles long and all under the shadow of Split Rock. Highway 287 cuts a diagonal across it and an occasional ranch or mine road appears, but the Oregon Trail was there first and, for a motorcyclist, is still the best avenue of travel.

We spent a day and a half making the trip, covering ground that few had traveled since the last emigrant wagon rolled west, and seeing the sights that Pony Express riders never had time to appreciate. It was for us, as it had been for them, a time of rocky ridges, water crossings, tremendous climbs, steep descents, dry washes, sage, sand, sun and sweat.

Pete’s trail ride came to an end in the middle of the desert at a place called Three Crossings. Here the trail and the Sweetwater River squeeze together and intersect three times as both attempt to negotiate a narrow pass through the Sweetwater Rocks. Pete dropped the front wheel of the Trail 90 into a hidden ditch of latter-day origin, and did a swan over the bars. The kink in the 90’s front wheel almost matched the kink in Pete’s back. Both were eventually fixed in suitable repair shops.

Still, we enjoyed the desert tremendously. More, we agreed, than the pioneers did.

At the end of the desert the Sweetwater River disappears into a deep and barren canyon. The trail follows it in, hesitates, then climbs out over the north rim to encounter Rocky Ridge, a wheel-breaking series of granite outcrops that have the weird appearance of ancient torture devices. To this point, four-wheel drive vehicles can follow the trail. From here on it’s two-wheel country.

Once over Rocky Ridge I paused to look around. Pete and Paul had taken the vehicles around the long way and would meet me at Atlantic City, a mining ghost town some 30 miles distant. To my left was the rim of the beautiful Sweetwater Canyon. To my right was the snow-covered south end of the Wind River Mountains. Ahead, over the reflective surface of the alkaline Lewiston Lakes was the famous South Pass. This, for Trail travelers, was the top of the world.

The Cub was feeling the effects of the 8000-ft. altitude. It was tuned for about 5500 ft., and the added height really showed up in sluggish performance. It was running well, it just seemed a bit relaxed.

I passed the three lakes, noticing a large, stone arrow pointing an older Indian trail and started across rolling, sage-covered country. In each low spot, lingering snow banks leaked water that slowly became rivulets feeding the Sweetwater. The damp soil took on a spongy quality that felt bottomless. I topped a higher hill and saw a small 4-wheel-drive vehicle ahead, and was surprised. I hadn’t expected company.

As I rode closer I noticed that the vehicle didn’t appear to have any wheels—no, they were there, all right, buried in one of the spongy bogs, right to the frame.

The owner came from behind and waved for help. I rode across the bog, trying to look casual, parked on high ground and walked back. It was a 3-hour job with jacks, rocks, logs and winch. As I said, this is strictly twowheel country.

At Rock Creek I examined the place where 77 members of Captain James G. Willie’s Mormon handcart company met their end in an October blizzard in 1856. A month later another handcart company, led by Captain Edward Martin lost 145 members in a similar storm nearby. That year, 1856, was bad for handcart travel on the Oregon Trail.

I kept a late appointment with Pete and Paul before continuing on through Willow Creek-gas tank deep but the Cub made it somehow—and to the ninth and last crossing of the Sweetwater at Burnt Ranch. Once across, the trail heads straight west over several miles of flat prairie and crosses a low hill that turns out to be the Continental Divide that separates the waters of the Pacific from those of the Atlantic. From the top it is only a short run to a bubbling display of clear, cold water headed west called Pacific Springs.

Near this point the trail divides into many branches headed for different destinations. The Mormon and Bridger Trails head southwest for Fort Bridger and the Salt Lake Valley. The Sublette Cutoff takes travelers due west for California. Lander’s Cutoff heads northwest for Oregon. Sub-branches provide alternate routes and shortcuts.

But, for now, we had traveled far enough to get the feel of the Trail and to wonder at the courage of men and women who crossed it in wagons containing the total of their worldly possessions. They were headed for the unknown in a very real sense. Today’s astronauts have, at least, the benefit of exploration by unmanned satélites. The emigrants of the 1800s had none.

Since my initial trip with Paul and Pete, I have spent a great deal of time on the Oregon Trail, riding the Cub, carefully, with the equipment necessary for professional 16-mm motion picture photography in a pack on my back. I have photographed reflections of the rising sun in the Sweetwater River and the setting sun in the distinctive notch of Split Rock. I have rested and had lunch at the historic pioneer campground under the massive stone arch of Natural Bridge. I have camped on the South Pass, breaking through river ice to get water for morning coffee and riding in 90-degree heat two hours later.

I have traveled the Oregon Trail and all of its major branches as well as is possible 100 years after its last major use. It has been a truly great experience.

Those who’d like to make the trip can drop by Cheyenne. I’ll show them the pictures and point-in the right direction—and that’s more help than the pioneers got.