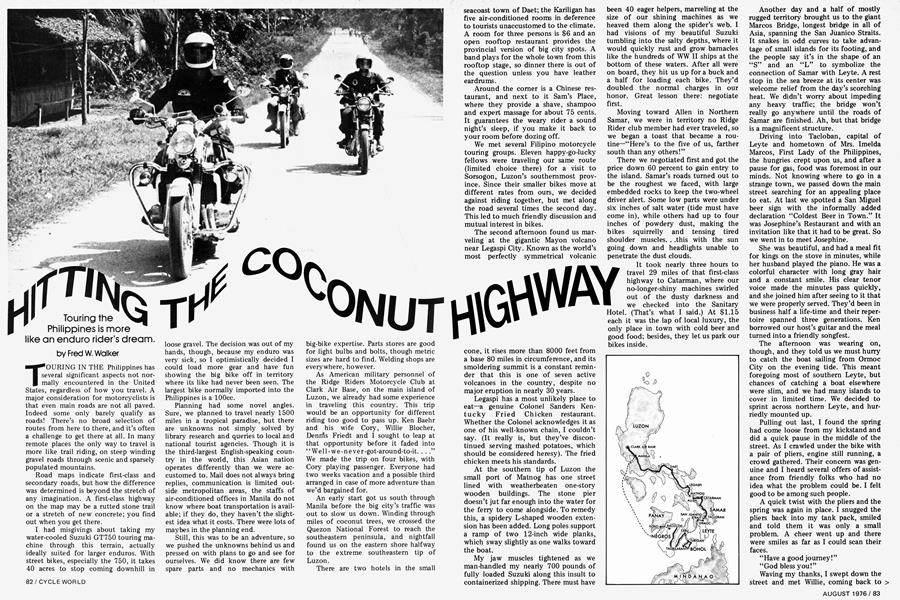

HITTING THE COCOUNT HIGHWAY

Touring the Philippines is more like an enduro rider's dream.

Fred W. Walker

TOURING IN THE Philippines has several significant aspects not normally encountered in the United States, regardless of how you travel. A major consideration for motorcyclists is that even main roads are not all paved. Indeed some only barely qualify as roads! There’s no broad selection of routes from here to there, and it’s often a challenge to get there at all. In many remote places the only way to travel is more like trail riding, on steep winding gravel roads through scenic and sparsely populated mountains.

Road maps indicate first-class and secondary roads, but how the difference was determined is beyond the stretch of any imagination. A first-class highway on the map may be a rutted stone trail or a stretch of new concrete; you find out when you get there.

I had misgivings about taking my water-cooled Suzuki GT750 touring machine through this terrain, actually ideally suited for larger enduros. With street bikes, especially the 750, it takes 40 acres to stop coming downhill in loose gravel. The decision was out of my hands, though, because my enduro was very sick, so I optimistically decided I could load more gear and have fun showing the big bike off in territory where its like had never been seen. The largest bike normally imported into the Philippines is a lOOcc.

Planning had some novel angles. Sure, we planned to travel nearly 1500 miles in a tropical paradise, but there are unknowns not simply solved by library research and queries to local and national tourist agencies. Though it is the third-largest English-speaking country in the world, this Asian nation operates differently than we were accustomed to. Mail does not always bring replies, communication is limited outside metropolitan areas, the staffs of air-conditioned offices in Manila do not know where boat transportation is available; if they do, they haven’t the slightest idea what it costs. There were lots of maybes in the planning end.

Still, this was to be an adventure, so we pushed the unknowns behind us and pressed on with plans to go and see for ourselves. We did know there are few spare parts and no mechanics with big-bike expertise. Parts stores are good for light bulbs and bolts, though metric sizes are hard to find. Welding shops are everywhere, however.

As American military personnel of the Ridge Riders Motorcycle Club at Clark Air Base, on the main island of Luzon, we already had some experience in traveling this country. This trip would be an opportunity for different riding too good to pass up. Ken Baehr and his wife Cory, Willie Blocher, Denrñs Friedt and I sought to leap at that opportunity before it faded into “Well-we-never-got-around-to-it. . . .” We made the trip on four bikes, with Cory playing passenger. Everyone had two weeks vacation and a possible third arranged in case of more adventure than we’d bargained for.

An early start got us south through Manila before the big city’s traffic was out to slow us down. Winding through miles of coconut trees, we crossed the Quezon National Forest to reach the southeastern peninsula, and nightfall found us on the eastern shore halfway to the extreme southeastern tip of Luzon.

There are two hotels in the small seacoast town of Daet; the Kariligan has five air-conditioned rooms in deference to tourists unaccustomed to the climate. A room for three persons is $6 and an open rooftop restaurant provides the provincial version of big city spots. A band plays for the whole town from this rooftop stage, so dinner there is out of the question unless you have leather eardrums.

Around the corner is a Chinese restaurant, and next to it Sam’s Place, where they provide a shave, shampoo and expert massage for about 75 cents. It guarantees the weary rider a sound night’s sleep, if you make it back to your room before dozing off.

We met several Filipino motorcycle touring groups. Eleven happy-go-lucky fellows were traveling our same route (limited choice there) for a visit to Sorsogon, Luzon’s southernmost province. Since their smaller bikes move at different rates from ours, we decided against riding together, but met along the road several times the second day. This led to much friendly discussion and mutual interest in bikes.

The second afternoon found us marveling at the gigantic Mayon volcano near Legaspi City. Known as the world’s most perfectly symmetrical volcanic

cone, it rises more than 8000 feet from a base 80 miles in circumference, and its smoldering summit is a constant reminder that this is one of seven active volcanoes in the country, despite no major eruption in nearly 30 years.

Legaspi has a most unlikely place to eat—a genuine Colonel Sanders Kentucky Fried Chicken restaurant. Whether the Colonel acknowledges it as one of his well-known chain, I couldn’t say. (It really is, but they’ve discontinued serving mashed potatoes, which should be considered heresy). The fried chicken meets his standards.

At the southern tip of Luzon the small port of Matnog has one street lined with weatherbeaten one-story wooden buildings. The stone pier doesn’t jut far enough into the water for the ferry to come alongside. To remedy this, a spidery L-shaped wooden extension has been added. Long poles support a ramp of two 12-inch wide planks, which sway slightly as one walks toward the boat.

My jaw muscles tightened as we man-handled my nearly 700 pounds of fully loaded Suzuki along this insult to containerized shipping. There must have been 40 eager helpers, marveling at the size of our shining machines as we heaved them along the spider’s web. I had visions of my beautiful Suzuki tumbling into the salty depths, where it would quickly rust and grow barnacles like the hundreds of WW II ships at the bottom of these waters. After all were on board, they hit us up for a buck and a half for loading each bike. They’d doubled the normal charges in our honor. Great lesson there: negotiate first.

Moving toward Allen in Northern Samar, we were in territory no Ridge Rider club member had ever traveled, so we began a toast that became a routine—“Here’s to the five of us, farther south than any others!”

There we negotiated first and got the price down 60 percent to gain entry to the island. Samar’s roads turned out to be the roughest we faced, with large embedded rocks to keep the two-wheel driver alert. Some low parts were under six inches of salt water (tide must have come in), while others had up to four inches of powdery dust, making the bikes squirrelly and tensing tired shoulder muscles. . .this with the sun going down and headlights unable to penetrate the dust clouds.

It took nearly three hours to travel 29 miles of that first-class highway to Catarman, where our no-longer-shiny machines swirled out of the dusty darkness and we checked into the Sanitary Hotel. (That’s what I said.) At $1.15 each it was the lap of local luxury, the only place in town with cold beer and good food; besides, they let us park our bikes inside.

Another day and a half of mostly rugged territory brought us to the giant Marcos Bridge, longest bridge in all of Asia, spanning the San Juanico Straits. It snakes in odd curves to take advantage of small islands for its footing, and the people say it’s in the shape of an “S” and an “L” to symbolize the connection of Samar with Leyte. A rest stop in the sea breeze at its center was welcome relief from the day’s scorching heat. We didn’t worry about impeding any heavy traffic; the bridge won’t really go anywhere until the roads of Samar are finished. Ah, but that bridge is a magnificent structure.

Driving into Tacloban, capital of Leyte and hometown of Mrs. Imelda Marcos, First Lady of the Philippines, the hungries crept upon us, and after a pause for gas, food was foremost in our minds. Not knowing where to go in a strange town, we passed down the main street searching for an appealing place to eat. At last we spotted a San Miguel beer sign with the informally added declaration “Coldest Beer in Town.” It was Josephine’s Restaurant and with an invitation like that it had to be great. So we went in to meet Josephine.

She was beautiful, and had a meal fit for kings on the stove in minutes, while her husband played the piano. He was a colorful character with long gray hair and a constant smile. His clear tenor voice made the minutes pass quickly, and she joined him after seeing to it that we were properly served. They’d been in business half a life-time and their repertoire spanned three generations. Ken borrowed our host’s guitar and the meal turned into a friendly songfest.

The afternoon was wearing on, though, and they told us we must hurry to catch the boat sailing from Ormoc City on the evening tide. This meant foregoing most of southern Leyte, but chances of catching a boat elsewhere were slim, and we had many islands to cover in limited time. We decided to sprint across northern Leyte, and hurriedly mounted up.

Pulling out last, I found the spring had come loose from my kickstand and did a quick pause in the middle of the street. As I crawled under the bike with a pair of pliers, engine still running, a crowd gathered. Their concern was genuine and I heard several offers of assistance from friendly folks who had no idea what the problem could be. I felt good to be among such people.

A quick twist with the pliers and the spring was again in place. I snugged the pliers back into my tank pack, smiled and told them it was only a small problem. A cheer went up and there were smiles as far as I could scan their faces.

“Have a good journey!” “God bless you!”

Waving my thanks, I swept down the street and met Willie, coming back to check on me. It’s nice to travel with friends; help’s there if you need it.

A rapid ride through some of the world’s most beautiful country brought us to Ormoc before nightfall—only to find the boat would be delayed two days. After all, it was Holy Thursday, and then Good Friday. In a predominantly Catholic country schedules become rather flexible around Easter. So we explored the local area, went swimming in the clear waters of Ormoc Bay, and met a friendly trio of brothers who welcomed our no-notice company. One brother was the mayor, another a sugar plantation owner, and the other a full time grandfather. Their conversation ranged from World War II battles to distilling and marketing rum in the current business world.

The last morning in Ormoc brought a hassle lasting most of the day. The shipping office would not consider our bikes until we had proper clearance from the Philippine Constabulary (the national police, known colloquially as the P.C.) authorizing us to move them from one island to another.

At the P.C. office a few miles away, we found we needed copies of our registration papers. These were available at small cost downtown in the opposite direction. Hurrying back with the copies, we found a long wait while the bureaucratic machinery ground out the necessary papers. Fortunately, no one asked how we’d gotten the bikes to Leyte in the first place. At last we headed back to the shipping office for another small mountain of paper work.

This time the ship’s crane put the machines aboard in one simple operation. Loading fees are about the same, regardless of whether it’s done by hand or machine. At least we’d learned to negotiate.

We changed ships in the port of Cebu; sort of like changing to the crosstown bus, except we didn’t have transfer passes. The paper work was required again. We also encountered a fellow who tried to rip us off by charging freight rates based on the value of our bikes instead of their weight and volume. When we asked to see his tariff book, he very quickly discovered it had been misplaced, but saved face by allowing us to ship our cargo at normal rates if we declared our bikes worth about $80 each.

Arriving at Tubigan, Bohol, at one o’clock in the morning, we slept aboard ship until sun-up. Our Easter sunrise service included off-loading the bikes by hand and finding a welder for Ken’s saddlebag supports,' which had held together with safety wire and hose clamps for three days. Luck was with us, and even on Easter morning an old man was happy to open his shop for strangers in need. His shop happened to be next door to a small cardineria serving excellent scrambled eggs. Fueled, fixed and fed, we were off in search of the famous Chocolate Hills of Bohol.

Things kept dropping from Ken’s bike throughout the trip, so to avoid loss, we didn’t let him ride drag position. This morning was just not his time for a tight pack, and he lost a canteen, a small bag and a rain suit in rapid succession. Pausing to look for the rain suit led to our meeting an immigrant farmer from the United States, who invited us back to spend the night.

The Chocolate Hills are a geological phenomenon known to exist in only two or three places in the world. Actually they are not brown, and chocolate does not grow in the region. Instead, the name is derived from their shape, exactly like that of a chocolate drop. Rising mysteriously a few hundred feet from the flat terrain, hundreds heap their symmetrical mounds as far as the eye can see. They are also sometimes called Haycock Hills. Geologists do not agree on their origin, but the theory probably most widely held is that they were once bubbles of volcanic limestone suddenly hardened beneath the sea. Some great shift of the earth brought them to the surface to form the island of Bohol, and erosion of a lighter substance, into which the bubbles had risen, left these weird shapes to confound today’s traveler.

On the road back to Carl Vancil’s farm Ken had apparently grown tired of dropping small things from his bike and decided to go all the way. He dropped the whole bike. In loose gravel, with the sun in his eyes and his sunglasses broken, an instant’s inattention was all it took. Not a bad spill, just a couple of scratches and bruises and hurt pride. Protective clothing, even in this extremely hot climate, is of as great a value as anywhere else. Little pains could have been serious problems, but as it was he and Cory dusted themselves off and we all bemoaned the loss of his windshield and a mirror. Since it was only a couple of miles, we forewent first aid and drove on to the farm.

We dubbed Carl the Gentleman Farmer of Bohol and enjoyed the hospitality of one glad to see some countrymen in this isolated spot on the other side of the world. Carl is retired from the U.S. Navy and has found a charming place to pursue his agricultural interests. He’s brought new ideas, such as introducing rabbits as a food source, and, in a convenient cave in one of his Chocolate Hills, are the beginnings of a commercial mushroom crop.

We slept in his nipa hut, where a flock of ducks had the ground floor, showed the kids our motors and talked of experimental farming in the tropics. Mrs. Vancil is a native of the Visayan islands and told us much about the people and how they live, not to mention giving us a few handy tips on dealing with shipping people and small business establishments. With them we attended a ceremony in the nearby village of Sagbayan, marking the introduction of electricity to the town. In a few months the lines will be extended to the farm. Progress is everywhere.

With an invitation to pause again at Carl’s other house in Cebu City, we hit the dusty road to visit the mayor of Tagbilaran, Bohol’s capital city. Mayor Inting is a friend and business acquaintance of Cory’s, but we’d given him no notice of our coming due to limited communications and our uncertain schedule.

Surprises cannot catch a Filipino off stride in hospitality, though; we were his guests for dinner at an interesting wharf restaurant built over the water. There was no tourist atmosphere at all. I don’t even think it had a name, but the dinner was superb.

Besides barbecued chicken they’d imported from shore, there were some fresh squid, both grilled and raw, a delicious salad dish of pickled raw fish, and a most excellent grilled white flat fish called lapu-lapu. It was similar to scampi, but definitely better eating. The cook had no teeth, grinned a lot and didn’t speak a word of English, but he could gather a few votes for chef of the year.

To wash down all this gastronomic delight required a couple of gallons of fresh tuba. Tuba is wine normally made from the sap of coconut palms, though it may also be made from nipa or buri palms. Ordinarily it must be made daily and consumed promptly because of spoilage, although in some regions it is put through some sort of distilling process and ends up clear and smooth, like very fine vodka. This was the fresh kind—sweet, cloudy, reddish rust colored and still bubbling—like hard cider about ten days old and cold.

We started slow and anything but early next morning, but the road back to Tubigan was good and we were in time to catch the last boat. As it pulled away, we realized we’d missed lunch in the hustle, but Cory opened some bags she’d mysteriously obtained while we loaded. She had fresh boiled crabs, grilled shrimp and little packets of rice wrapped in palm leaves. There was even a grilled squid for Willie (his favorite) and the biggest prawn I’ve ever seen. We feasted right there on the deck, got greasy fingers, threw the bio-degradable parts in the sea and hardly noticed the time pass until we docked again in Cebu.

Carl’s house was easy to find and we relaxed there for a couple of days, taking the opportunity to tend mechanical needs. Cables and chains needed lube and adjustment, and there were a host of minor items, but the machines were all holding up very well in spite of continuous rough treatment. The Hondas, an XL350, a CB360 and a CB350, needed only minor attention, and the Suzuki will go for a lifetime when properly tuned. Carl didn’t want us to have grease on our fingers all the time, so showed us some sights in the oldest and second-largest city in the Philippines. He didn’t neglect night spots either, making us decide to head on down the road before acute debilitation felled us all. In a flash of poor judgment, we changed our toast to, “. . .smashed farther south than any others!”

South and around the tip of Cebu we found a ferry made for vehicles. No big ocean-going ship, but a catamaran pulled up to a good solid pier so that we could drive aboard. The price was really right: two pesos (30 cents) and no loading fee for passage to Negros. The cat was wide and fairly stable, but the water was choppy.

In the village of Bais on Negros Island we found the only hotel for many miles as darkness closed on us. Because the supply does not meet the demand, electricity is provided to half the town and then switched to the other half every 30 minutes. This led to a candlelight dinner. One room for us all with a shower down the hall was fine, and we each had a mosquito net. For once, none of the hungry little buzzers made it through my net. The only problem was a large red and black parrot, or similar species, which sat on a perch about 10 feet from our window. This bird could do a highly realistic imitation of a pig being slaughtered, and he practiced all night.

Next morning I set another new club record. I was farthest south to have a flat tire!

It had to be the big Suzuki, of course. The situation was more difficult to face because we were riding the euphoria of a relatively troublefree trip to this point. A tip of the hat and many thanks to the design engineers who built the little drop-out plugs into the swinging arm, allowing us to pull the wheel without dropping the exhaust pipes. The curious crowd, something a foreigner can never be without here, told us there were no vulcanizing shops within 20 klicks. So we wasted no time looking for one, simply swapped the tube and used the engine pump.

That was a long hot day. We passed miles of sugar plantations and a couple of large seaside lumber mills. It was harvest time and long trains piled high with sugar cane inched across the heatshimmering fields and crisscrossed the dusty road. Ken sheared a mounting bolt on a rough stretch, which left him with a loose fender, luggage rack and saddle bag. The next town’s hardware store had a small selection of the wrong bolts, so it took more than an hour to rig a suitable modified replacement. Sweat was dripping from the ends of our noses and burning eyes as we finished to see the sun getting low.

(Continued on page 108)

Continued from page 85

We had a long way to go and hated to drive at night after a hard day; but the townspeople brought out cold beer. . .and that hospitality, from folks who have little enough themselves, cannot be refused. So we paused for some friendly gossip before a sunset ride through the last rolling hills of sugar cane.

The sun had just stopped burning my eyes and slid below the low hills when I was afflicted with another flat. (Wonderful day). It was sudden this time and the Suzi got squirrelly in the gravel as I tried to bring it to a stop without running off for an earful of sugar cane.

By the time the others circled back I had a marker in the road to ward off oncoming trucks, had the bolts loose and was ready to drop the wheel. The luck of the day held and we were again miles from a vulcanizing shop. We swapped tubes, working against time—it would soon be full dark, and who wants to change a flat in the dark miles from nowhere. Besides, we didn’t have cold beer out there.

Bacolod, capital city of Negros Occidental province, finally gleamed out of the darkness and we rolled wearily into the heart of town. Deciding we owed it to ourselves after that day, we splurged and checked in at a tourist class hotel with hot showers. After a late feast we could barely make it to our beds for a sound sleep, but in the morning the American Embassy found us.

Return to duty was the message. We were ready, but there was a small matter of several hundred miles of water and limited shipping schedules.

That day’s boat had four openings and maybe we could squeeze in a fifth on deck, but the schedule was tight. There would be a change of boats at the next island and they didn’t think we could make the switch with the bikes. Tomorrow’s boat was already oversold, and the only other possibility was a livestock freighter leaving two days later and taking 30 hours to reach Manila. Things looked bleak, so we asked to see the manager; after several wait-heres we were ushered into the office of Attor-> ney Ledesma, branch manager of the Negros Navigation Company.

After hearing our plight, he carefully went over shipping schedules with us, and we decided our best bet was still to try and make the tight connection that same day. He didn’t think we could, but offered to help by sending a message through the company system requesting that our movement be expedited. With many thanks we hurried back to the booking office.

Of course, we had to get our police clearance, but the others went to pack while Willie and I completed the paper work. Those who hire a travel agent to arrange things miss all this good bureaucratic business, but we were on the do-it-yourself economy plan and wanted to get our money’s worth in red tape too. The manager’s word smoothed it some, and we were soon off to the races.

The first boat was no trouble. We relaxed until the dock in Iloilo City, then were first off and over to the other ship where they were frantically loading cargo. In the rush I began to wonder if we could get anyone’s attention with only five minutes until they were to cast loose. The load crew foreman wasn’t hard to spot; he had a battery megaphone in one hand, a fistful of papers in the other. The problem was getting to talk to him. He was moving like a pelota ball in a championship doubles tournament. (Pelota is a popular game here. It’s like handball or paddle ball without as many walls).

One of my bright ideas for cutting red tape struck home. The solution was to drive the Suzuki right up to where the winch was operating. This indeed got his attention.

He said, “Get the hell outta the way!”

We did get in, riding up with the last of the cargo because they’d removed the gangplank by the time we got the bikes up. We settled the shipping fees on board, another of Attorney Ledesma’s short cuts, then relaxed for the overnight cruise to Manila and home.

Looking back as we steamed into the dark waters of Manila Bay, I reflected on the wonder of this fantastic adventure. We’d traveled 1400 miles on all kinds of roads, and more miles than that by sea, through some of the most breathtaking beautiful tropical terrain I ever hope to see. We’d met some of the finest and friendliest people in this wide world. The street bikes held up as well as the enduros, and the experience gave us a wealth of knowledge we and our fellow club members can draw upon. We can make another trip with half the planning worries, save time and see more places by knowing how and where, and enjoy the Philippine scene even more. I’m ready to go again, and ask only for a little more time to do it in.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsRound Up

AUGUST 1976 By Joe Parkhurst -

Departments

DepartmentsLetters

AUGUST 1976 -

Departments

DepartmentsFeed Back

AUGUST 1976 -

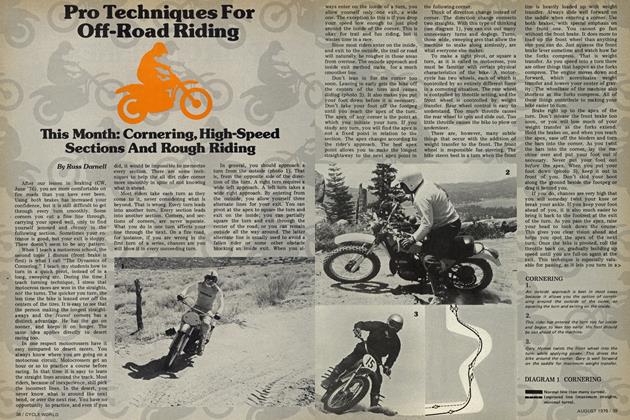

How To Ride

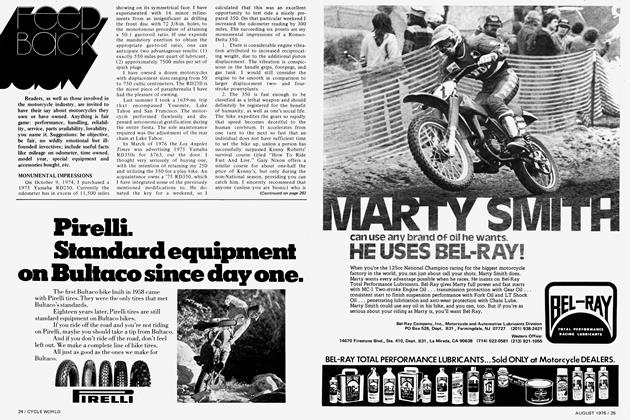

How To RidePro Techniques For Off-Road Riding

AUGUST 1976 By Russ Darnell -

Special Test

Special TestSuzuki's Rm125 What It Takes To Make It Right

AUGUST 1976 -

Competition

CompetitionCamel Pro Series

AUGUST 1976