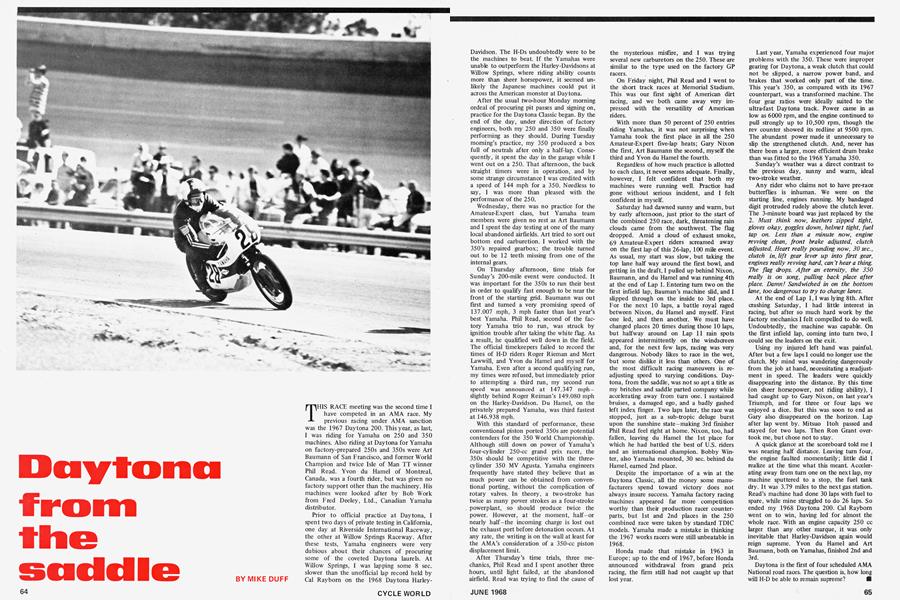

Daytona from the saddle

MIKE DUFF

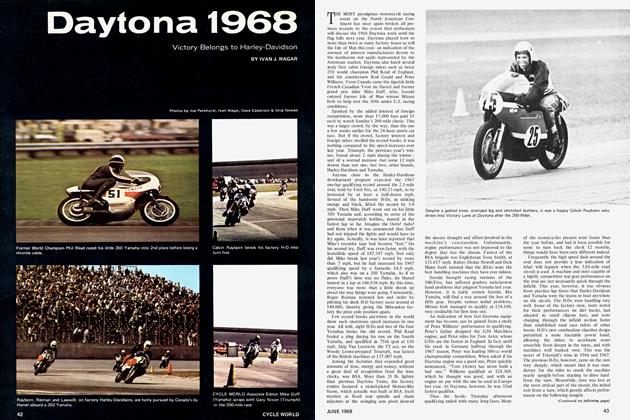

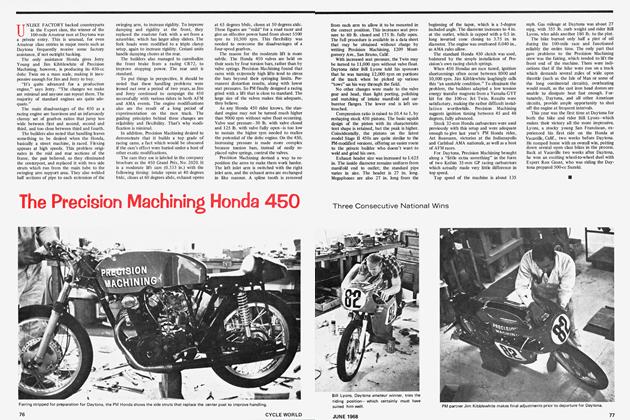

THIS RACE meeting was the second time I have competed in an AMA race. My previous racing under AMA sanction was the 1967 Daytona 200. This year, as last, I was riding for Yamaha on 250 and 350 machines. Also riding at Daytona for Yamaha on factory-prepared 250s and 350s were Art Baumann of San Francisco, and former World Champion and twice Isle of Man TT winner Phil Read. Yvon du Hamel of Montreal, Canada, was a fourth rider, but was given no factory support other than the machinery. His machines were looked after by Bob Work from Fred Deeley, Ltd., Canadian Yamaha distributor.

Prior to official practice at Daytona, I spent two days of private testing in California, one day at Riverside International Raceway, the other at Willow Springs Raceway. After these tests, Yamaha engineers were very dubious about their chances of procuring some of the coveted Daytona laurels. At Willow Springs, I was lapping some 8 sec. slower than the unofficial lap record held by Cal Raybom on the 1968 Daytona HarleyDavidson. The H-Ds undoubtedly were to be the machines to beat. If the Yamahas were unable to outperform the Harley-Davidsons at Willow Springs, where riding ability counts more than sheer horsepower, it seemed unlikely the Japanese machines could put it across the American monster at Daytona.

After the usual two-hour Monday morning ordeal of procuring pit passes and signing on, practice for the Daytona Classic began. By the end of the day, under direction of factory engineers, both my 250 and 350 were finally performing as they should. During Tuesday morning’s practice, my 350 produced a box full of neutrals after only a half-lap. Consequently, it spent the day in the garage while I went out on a 250. That afternoon, the back straight timers were in operation, and by some strange circumstance I was credited with a speed of 144 mph for a 350. Needless to say, I was more than pleased with the performance of the 250.

Wednesday, there was no practice for the Amateur-Expert class, but Yamaha team members were given no rest as Art Baumann and I spent the day testing at one of the many local abandoned airfields. Art tried to sort out bottom end carbure ti on. I worked with the 350’s repaired gearbox; the trouble turned out to be 12 teeth missing from one of the internal gears.

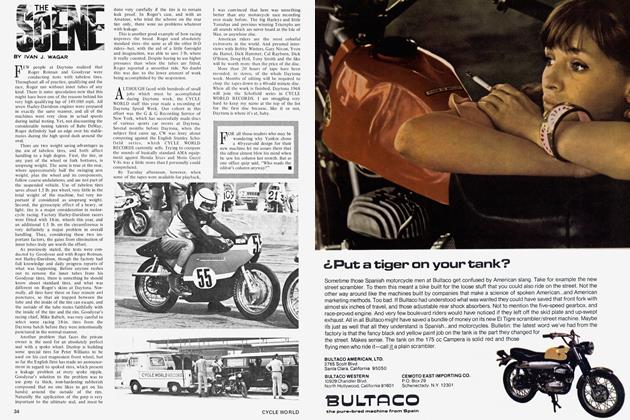

On Thursday afternoon, time trials for Sunday’s 200-mile event were conducted. It was important for the 350s to run their best in order to qualify fast enough to be near the front of the starting grid. Baumann was out first and turned a very promising speed of 137.007 mph, 3 mph faster than last year’s best Yamaha. Phil Read, second of the factory Yamaha trio to run, was struck by ignition trouble after taking the white flag. As a result, he qualified well down in the field. The official timekeepers failed to record the times of H-D riders Roger Rieman and Mert Lawwill, and Yvon du Hamel and myself for Yamaha. Even after a second qualifying run, my times were refused, but immediately prior to attempting a third run, my second run speed was announced at 147.347 mph— slightly behind Roger Reiman’s 149.080 mph on the Harley-Davidson. Du Hamel, on the privately prepared Yamaha, was third fastest at 146.938 mph.

With this standard of performance, these conventional piston ported 350s are potential contenders for the 350 World Championship. Although still down on power of Yamaha’s four-cylinder 250-cc grand prix racer, the 350s should be competitive with the threecylinder 350 MV Agusta. Yamaha engineers frequently have stated they believe that as much power can be obtained from conventional porting, without the complication of rotary valves. In theory, a two-stroke has twice as many power strokes as a four-stroke powerplant, so should produce twice the power. However, at the moment, half-or nearly half-the incoming charge is lost out the exhaust port before detonation occurs. At any rate, the writing is on the wall at least for the AMA’s consideration of a 350-cc piston displacement limit.

After Thursday’s time trials, three mechanics, Phil Read and I spent another three hours, until light failed, at the abandoned airfield. Read was trying to find the cause of the mysterious misfire, and I was trying several new carburetors on the 250. These are similar to the type used on the factory GP racers.

On Friday night, Phil Read and I went to the short track races at Memorial Stadium. This was our first sight of American dirt racing, and we both came away very impressed with the versatility of American riders.

With more than 50 percent of 250 entries riding Yamahas, it was not surprising when Yamaha took the first place in all the 250 Amateur-Expert five-lap heats; Gary Nixon the first, Art Baumann the second, myself the third and Yvon du Hamel the fourth.

Regardless of how much practice is allotted to each class, it never seems adequate. Finally, however, I felt confident that both my machines were running well. Practice had gone without serious incident, and I felt confident in myself.

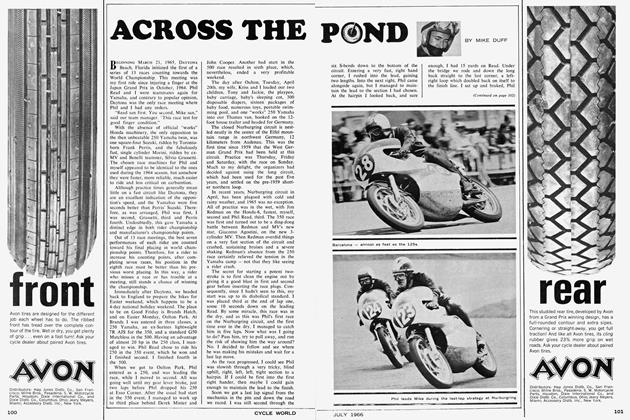

Saturday had dawned sunny and warm, but by early afternoon, just prior to the start of the combined 250 race, dark, threatening rain clouds came from the southwest. The flag dropped. Amid a cloud of exhaust smoke, 69 Amateur-Expert riders screamed away on the first lap of this 26-lap, 100 mile event. As usual, my start was slow, but taking the top lane half way around the first bowl, and getting in the draft, I pulled up behind Nixon, Baumann, and du Hamel and was running 4th at the end of Lap 1. Entering turn two on the first infield lap, Bauman’s machine slid, and I slipped through on the inside to 3rd place. For the next 10 laps, a battle royal raged between Nixon, du Hamel and myself. First one led, and then another. We must have changed places 20 times during those 10 laps, but halfway around on Lap 11 rain spots appeared intermittently on the windscreen and, for the next few laps, racing was very dangerous. Nobody likes to race in the wet, but some dislike it less than others. One of the most difficult racing maneuvers is readjusting speed to varying conditions. Daytona, from the saddle, was not so apt a title as my britches and saddle parted company while accelerating away from turn one. I sustained bruises, a damaged ego, and a badly gashed left index finger. Two laps later, the race was stopped, just as a sub-tropic deluge burst upon the sunshine state-making 3rd finisher Phil Read feel right at home. Nixon, too, had fallen, leaving du Hamel the 1st place for which he had battled the best of U.S. riders and an international champion. Bobby Winter, also Yamaha mounted, 30 sec. behind du Hamel, earned 2nd place.

Despite the importance of a win at the Daytona Classic, all the money some manufacturers spend toward victory does not always insure success. Yamaha factory racing machines appeared far more competition worthy than their production racer counterparts, but 1st and 2nd places in the 250 combined race were taken by standard TDIC models. Yamaha made a mistake in thinking the 1967 works racers were still unbeatable in 1968.

Honda made that mistake in 1963 in Europe; up to the end of 1967, before Honda announced withdrawal from grand prix racing, the firm still had not caught up that lost year.

Last year, Yamaha experienced four major problems with the 350. These were improper gearing for Daytona, a weak clutch that could not be slipped, a narrow power band, and brakes that worked only part of the time. This year’s 350, as compared with its 1967 counterpart, was a transformed machine. The four gear ratios were ideally suited to the ultra-fast Daytona track. Power came in as low as 6000 rpm, and the engine continued to pull strongly up to 10,500 rpm, though the rev counter showed its redline at 9500 rpm. The abundant power made it unnecessary to slip the strengthened clutch. And, never has there been a larger, more efficient drum brake than was fitted to the 1968 Yamaha 350.

Sunday’s weather was a direct contrast to the previous day, sunny and warm, ideal two-stroke weather.

Any rider who claims not to have pre-race butterflies is inhuman. We were on the starting line, engines running. My bandaged digit protruded rudely above the clutch lever. The 3-minute board was just replaced by the 2. Must think now, leathers zipped tight, gloves okay, goggles down, helmet tight, fuel tap on. Less than a minute now, engine revving clean, front brake adjusted, clutch adjusted. Heart really pounding now, 30 sec., clutch in, lift gear lever up into first gear, engines really revving hard, can’t hear a thing. The flag drops. After an eternity, the 350 really is on song, pulling back place after place. Damn! Sandwiched in on the bottom lane, too dangerous to try to change lanes.

At the end of Lap 1,1 was lying 8th. After crashing Saturday, I had little interest in racing, but after so much hard work by the factory mechanics I felt compelled to do well. Undoubtedly, the machine was capable. On the first infield lap, coming into turn two, I could see the leaders on the exit.

Using my injured left hand was painful. After but a few laps I could no longer use the clutch. My mind was wandering dangerously from the job at hand, necessitating a readjustment in speed. The leaders were quickly disappearing into the distance. By this time (on sheer horsepower, not riding ability), I had caught up to Gary Nixon, on last year’s Triumph, and for three or four laps we enjoyed a dice. But this was soon to end as Gary also disappeared on the horizon. Lap after lap went by. Mitsuo Itoh passed and stayed for two laps. Then Ron Grant overtook me, but chose not to stay.

A quick glance at the scoreboard told me I was nearing half distance. Leaving turn four, the engine faulted momentarily; little did I realize at the time what this meant. Accelerating away from turn one on the next lap, my machine sputtered to a stop, the fuel tank dry. It was 3.79 miles to the next gas station. Read’s machine had done 30 laps with fuel to spare, while mine struggled to do 26 laps. So ended my 1968 Daytona 200. Cal Raybom went on to win, having led for almost the whole race. With an engine capacity 250 cc larger than any other marque, it was only inevitable that Harley-Davidson again would reign supreme. Yvon du Hamel and Art Baumann, both on Yamahas, finished 2nd and 3rd.

Daytona is the first of four scheduled AMA National road races. The question is, how long will H-D be able to remain supreme? ■