ACROSS THE POND

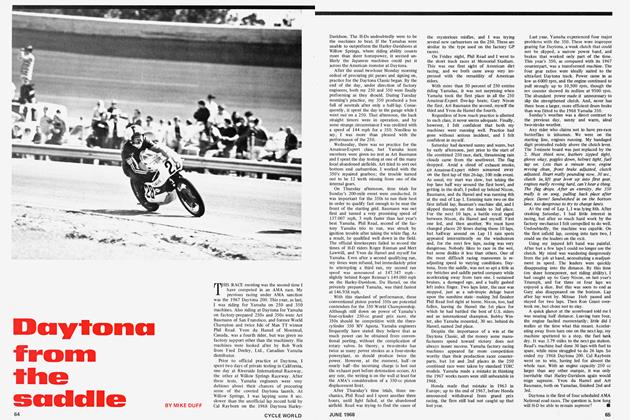

BEGINNING MARCH 21, 1965, DAYTONA Beach, Florida initiated the first of a series of 13 races counting towards the World Championship. This meeting was my first ride since injuring a finger at the Japan Grand Prix in October, 1964. Phil Read and I were teammates again for Yamaha, and contrary to popular opinion, Daytona was the only race meeting where Phil and I had any orders.

“Read san first. You second, Mike san,” said our team manager. “This race test for good finger condition.”

With the absence of official “works” Honda machinery, the only opposition to the then unbeatable 250 Yamaha twin, was one square-four Suzuki, ridden by Torontoborn Frank Perris, and the fabulously fast, single cylinder Morini, ridden by exMV and Benelli teamster, Silvio Grassetti. The chosen race machines for Phil and myself appeared to be identical to the ones used during the 1964 season, but somehow they were faster, more reliable, much easier to ride and less critical on carburetion.

Although practice times generally mean little on a fast circuit like Daytona, they are an excellent indication of the opposition’s speed, and the Yamahas were five seconds better than Perris’ Suzuki. Therefore, as was arranged, Phil was first, I was second, Grassetti, third and Perris fourth. Undoubtedly, this gave Yamaha a distinct edge in both rider championship and manufacturer’s championship points.

Out of 13 race meetings, the best seven performances of each rider are counted toward his final placing in world championship points. Therefore, for a rider to increase his counting points, after completing seven races, his position in the eighth race must be better than his previous worst placing. In this way, a rider who misses a race or has trouble at a meeting, still stands a chance of winning the championship.

Immediately after Daytona, we headed back to England to prepare the bikes for Easter weekend, which happens to be a 4-day national holiday weekend. The place to be on Good Friday is Brands Hatch, and on Easter Monday, Oulton Park. At Brands I was entered in three classes, a 250 Yamaha, an ex-Surtees lightweight 7R AJS for the 350, and a standard G50 Matchless in the 500. Having an advantage of almost 20 hp in the 250 class, I managed to win. Phil Read chose to ride his 250 in the 350 event, which he won and I finished second. I finished fourth in the 500.

When we got to Oulton Park, Phil entered as a 250, and was leading the race, while I moved to second. All was going well until my gear lever broke, just two laps before Phil dropped his 250 at Esso Corner. After the usual bad start in the 350 event, I managed to work up to third place behind Derek Minter and John Cooper. Another bad start in the 500 race resulted in sixth place, which, nevertheless, ended a very profitable weekend.

The day after Oulton, Tuesday, April 20th, my wife, Kriss and I loaded our two children, Tony and Jackie, the playpen, baby carriage, baby’s sleeping cot, 300 disposable diapers, sixteen packages of baby food, numerous toys, portable swimming pool, and one “works” 250 Yamaha into our Thames van, hooked on the 12foot house trailer and headed for Germany.

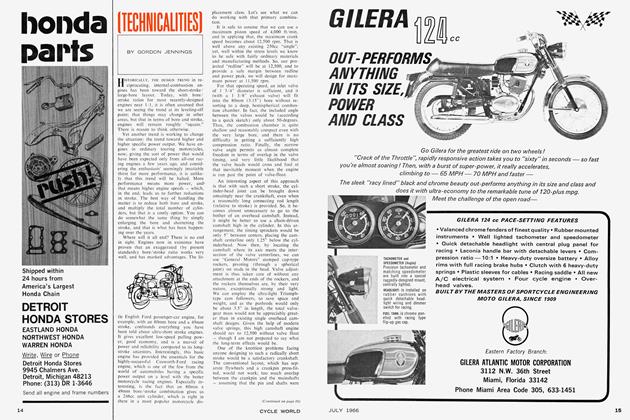

The closed Nurburgring circuit is nestled neatly in the center of the Eifel mountain range in northwest Germany, 12 kilometers from Audenau. This was the first time since 1959 that the West German Grand Prix had been held at this circuit. Practice was Thursday, Friday and Saturday, with the race on Sunday. Much to my delight, the organizers had decided against using the long circuit, which had been used for the past five years, and settled on the pre-1959 shorter northern loop.

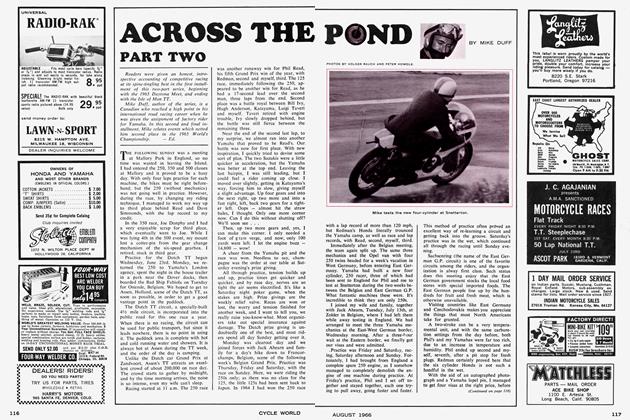

In recent years, Nurburgring circuit in April, has been plagued with cold and rainy weather, and 1965 was no exception. All of practice was in the wet, with Jim Redman on the Honda-6, fastest, myself, second and Phil Read, third. The 350 race was first and turned out to be a ding-dong battle between Redman and MV’s new star, Giacomo Agostini, on the new 3cylinder MV. Then Redman overdid things on a very fast section of the circuit and crashed, sustaining bruises and a severe shaking. Redman’s absence from the 250 race certainly relieved the tension in the Yamaha camp — not that they like seeing a rider crash.

The secret for starting a potent twostroke is to first clean the engine out by giving it a good blast in first and second gear before inserting the race plugs. Consequently, since I hadn’t seen to this, my start was up to its diabolical standard. I was placed third at the end of lap one, some 10 seconds down on the leading Read. By some miracle, this race was in the dry, and as this was Phil’s first race on the Nurburgring circuit, and the first time ever in the dry, I managed to catch him in five laps. Now what was I going to do? Pass him, try to pull away, and run the risk of showing him the way around? No. I decided to follow and see where he was making his mistakes and wait for a last lap move.

As the race progressed, I could see Phil was slowish through a very tricky, blind uphill, right, left, left, right section to a hairpin. If I could be first into the first right hander, then maybe I could gain enough to maintain the lead to the finish.

Soon we got a last lap signal from the mechanics in the pits and down the road we raced. I was still second through the six S-bends down to the bottom of the circuit. Entering a very fast, right hand corner, I rushed into the lead, gaining two lengths. Into the next right, Phil came alongside again, but I managed to maintain the lead to the section I had chosen. At the hairpin I looked back, and sure

MIKE DUFF

enough, I had 15 yards on Read. Under the bridge we rode and down the long back straight to the last corner, a leftright loop which doubled back on itself to the finish line. I sat up and braked, Phil came alongside, but my advantage was not enough to prevent him from slipstreaming me down the straight. I still had a chance, until we tangled with a slower rider. Then Phil, who was on the inside, got through and I didn’t. Hence, I was second again, but I did have a good try. Phil also got the lap record on the ultimate lap, which indicates how much faster we were going.

(Continued on page 102)

Just as our race was over, the sidecars were due out. As the starter’s flag fell, the heavens opened and dropped hailstones the size of golfballs, which fortunately turned to snow. Fritz Scheidegger was first, with nothing more than eye glasses for protection. On Monday he looked as if he had been on an all-night binge . . . Well, maybe he had.

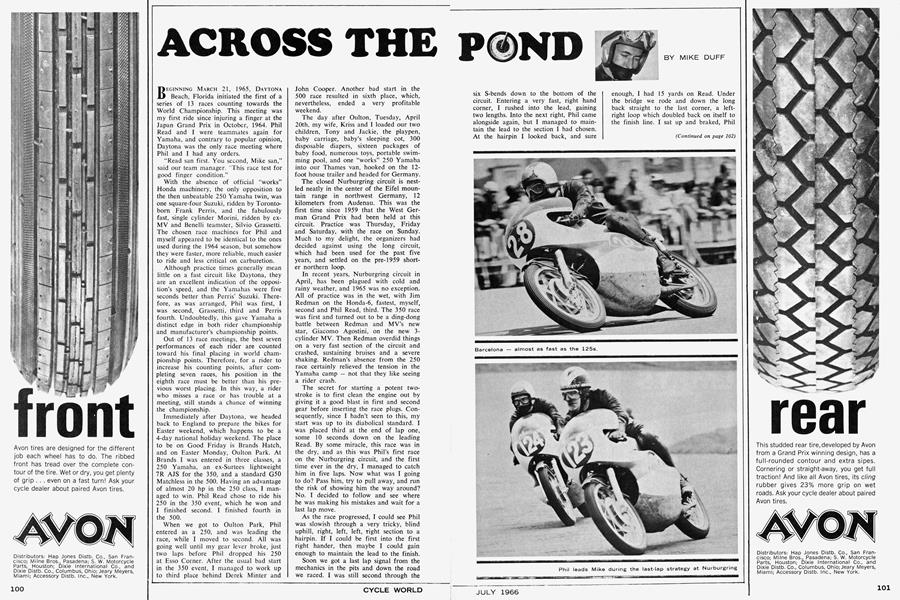

We had two weeks before the Spanish Grand Prix on May 9th. Being completely starved of sunshine, we unanimously voted to head out for Spain as soon as possible. Accompanied by three Japanese mechanics in their two-ton Opel van, we set off Monday afternoon, arriving in Barcelona, Friday morning. The weather was absolutely gorgeous.

After depositing the mechanics in their hotel, we headed out for one of the many camping sites south of Barcelona, about five miles from the circuit, to join Frank Perris and Ralph Bryans. The camping site covered some two square miles of park land, and was complete with a small shopping plaza, car wash, restaurant, bar, showers, and most important, 1,000 yards of sandy beach on the shores of the blue Mediterranean. Needless to say we accomplished absolutely nothing until practice began the following Thursday.

After a week of lying in the sun, none of us had much interest in resuming the task of sorting out machinery, getting carburetion right, selecting the best gear ratios and re-learning the nasty twists and turns of the narrow Montjuich Park circuit, which is in the heart of Barcelona’s two bull rings. (A Bull Ring is not a German racing circuit for loud-mouthed car racers.)

The Spanish Grand Prix caters for 50, 125, 250 and 500 sidecar classes only. Because Yamaha was only supporting the 250 event, the man to beat was twotime winner and lap record holder, Tarquinio Provini, on the 4-cylinder Benelli. Read was fastest in practice, Provini second, myself fifth — some 3 seconds slower than the fastest 125 time.

The 250 race developed into a terrific scrap between Read and Provini for first place. Ramon Torras and I battled for third spot. Torras was riding a standard water-cooled Bultaco. At this point I must say that I sincerely detest the Montjuich circuit, and that Ramon was an extremely capable rider. Unfortunately, he was killed at another race a few weeks later in Spain.

At the second from last lap, to my disgrace, Read came by. But where was Provini? Apparently, Provini had struck rear suspension problems and had stepped off, fortunately unhurt, letting Torras into second place.

The finish flag fell. Read was first, but he did not lap Torras. I was flagged off a lap early in third place and Torras sped on, only to run out of fuel half a mile from the finish. All he had to do was push home to be second, which he did.

If only I’d gone a bit quicker! There was one consolation, however. My time for the 250 race would have placed me second in the 125 race, which goes to prove that the most powerful machine is not always the most successful. The more power, the narrower the power band. The narrower the power band, the more gears you need. The more power, the bigger the frame. The heavier the machine, the harder to stop and harder to ride. So come on, Mr. Honda, bring out your 9-speed, 8-cylinder 250 as soon as you like. Personally, I’d welcome Mike Hailwood’s new headache.

The French Grand Prix was held the weekend after the Spanish, at the excellent Rouen circuit. This was the first time it had been held here, so it gave no rider an advantage. Practice was on Friday and Saturday. Thursday was spent with a pad and pencil studying the circuit, which is really terrific with lots of very fast swervery. As with most circuits, the most important corner appeared to be the last one.

“Works” machinery of today is usually so closely matched in all respects, that it is a toss of a coin on the last corner as to who gets to the finish line first. All this last lap strategy wqs a complete loss to me, as I dropped the plot on the second lap. This was a fitting end to the French Grand Prix, where I had spent the last three months arguing with the organizers over very poor starting money. Unfortunately, the organizers realize that the “works” teams will come anyway, regardless of the money, because of contract commitments.

For the year 1965, Yamaha officially supported the American Grand Prix, Isle of Man TT, Dutch TT and the Belgian and Japanese Grands Prix. For the remaining eight meetings, we were to enter privately in the 250 class only. Yamaha supplied three mechanics, one large Opel van, four 250-twins, about 2,000 spark plugs and enough spare parts to complete the season. In addition to these four machines, Phil and I each had a machine in England for the short circuit meetings. Needless to say we were more than pleased with three $50,000 machines apiece at our disposal.

On our return to England after the French G.P., we joined up with the newlyarrived team from Japan for the Isle of Man. They brought with them a completely new stable of six 250-twins and three of the new 8-speed water-cooled 125s, Before going over to the Island, we spent two days at Silverstone in England, trying to sort out all the bugs in the new bikes. The Isle of Man TT is no place to sort out new machinery, especially a two-'stroke.

It is always a joy to return to the Isle of Man, verdant and beautiful, surrounded by the deep blue waters of the Irish sea, a short 40 miles from Beatleland, Liverpool. Here is a motorcycle atmosphere, the likes of which cannot be found in any other place. Even the 85-year-old proprietor of the local grannies’ apparel shop is keen. And why not? The 150,000 people attracted to the races support the Island financially for the year.

(Continued on page 104)

Practice, which began Friday evening, June 2nd, was held every morning from 4:45 to 6:45 and every evening from six to eight p.m., until Saturday, June 10th. As I was competing in all four solo classes, I was up at four every morning, often working until midnight on the two larger machines. This was my sixth year on the Island, so only half a day was necessary to familiarize myself with the circuit. Riding the bigger classes is good practice for the lightweight machines, as the 125 was about the same speed as the 350, and likewise the 250 and 500.

The only disconcerting thing that happened during practice was never to complete more than one lap without trouble on the 125, for it was a very delicate little bicycle. However, I was very optimistic about finishing the 125 race, as it was over three laps of the most tortuous of circuits, a total of 113 miles. The other three races were six laps long.

Monday, June 12th, was the day of the 250 and sidecar races. Tt was dry, but cold, with a heavy cloud hanging over Snaefell mountain. Start of the 250 race was scheduled for 1:00 p.m. Riders start in pairs at 10-second intervals, in numerical order. Jim Redman was number 2, Phil Read, number 5 and myself, number 8. Read was the favorite, having lapped the circuit at an average speed of 99.4 mph in practice, and he had a good advantage over Redman by starting 20 seconds behind him. If he could catch Redman and hang on, he would be pretty well guaranteed of winning. Likewise for myself, if I could catch “Speedy.” But my practice times in all classes had been very poor, so I had no plan of attack, except to try as hard as possible. As it happened, Read caught Redman halfway around on the second lap, but was soon to retire with a broken crankshaft, letting Redman into first place.

Little Bill Ivy, who was recruited into the Yamaha team for the Isle of Man and the Dutch TT, was now a brilliant second, and myself, third. Unfortunately, Bill crashed in the fog and had to retire, but was not hurt. I was now second, about three minutes behind Redman, and some two minutes up on third place man, Frank Perris, on the 4-cylinder Suzuki. The race ended in that order, but Phil Read had stolen the limelight by becoming the first rider to lap the Isle of Man TT circuit at over 100 mph on a 250. For me, the 250 race was a bitter disappointment. Granted, I finished second, but in simple language, I rode like an old woman.

Wednesday morning was the 125 race, and a complete contrast. I’ve never ridden better on the Island.

Hugh Anderson was the hot favorite for this race, and he was to start 10 seconds behind me. My plan was to keep ahead of him, if possible. He caught up with me halfway around on the first lap, but by the end of the lap, he had dropped back, having to stop and change a plug. Ten miles out on lap 2, just past Sarah’s Cottage, Yamaha had a private signalling station (connected to start-finish by telephone). I learned I was two seconds down on Read.

Down the proceeding straight I almost overshot the braking point, thinking that if I went a bit quicker I might be able to WIN this race. It seemed I could do no wrong, and on the third and last lap a similar signal was given from Sarah’s Cottage. Then my luck ran out. Twentyfive miles further on at Creg-ny-Baa, my little beauty went onto one cylinder, and I limped home the remaining two miles on the other pot. This dropped me another place, but it was a very satisfying third. An added consolation was to learn that the first four riders had all broken the lap record from a standing start; but it was Anderson who put in the fastest time on his last lap at 96 mph.

My 350 mount was a 7R AJS, equipped with a 9/10ths gallon seat-fuel tank. This, combined with the main tank, would hold enough fuel to complete six laps non-stop. Such a contrast is the 350 to the little Yamaha, that it seemed to take ages to settle down on the 7R. However, while in fifth position on lap number 4, the overhead camshaft drive chain broke, demoting me to the “retired rider okay’’ bracket. Times like these are the only chances a rider gets to do any spectating A bit frightening if you ask me. However, I did manage to struggle up the road a quarter-mile to the nearest pub for a glass of John Courage . . . needed for spectating.

Redman eventually won this event after an epic struggle with Mike Hailwood, whose 3-cylinder MV eventually blew.

Friday’s 500 race was obviously not going to be the most enjoyable, with a heavy drizzle still falling from the day before. My G50 Matchless was really flying, and with a starting number 20, it didn’t take long to catch number 18, Paddy Driver. When weather conditions are poor, riding with another competitor is a good thing, because each will pull the other along. This way, concentration is not lost, the race seems much shorter and generally makes an otherwise arduous task as enjoyable as possible. A race of this type is a race to finish with no fireworks. Mike Hailwood won, even after dropping the MV, Joe Dunphy, second, myself, third.

On paper, the 1965 Isle of Man was a great financial success for me, but the only real satisfaction came from the 125 race. An interesting comparison is the difference in speeds between my four machines, 125 — 128 mph, 250 — 143 mph, 350 — 126 mph, 500 — 138 mph, all timed through the Highlander section of the course. E

CONTINUED NEXT MONTH