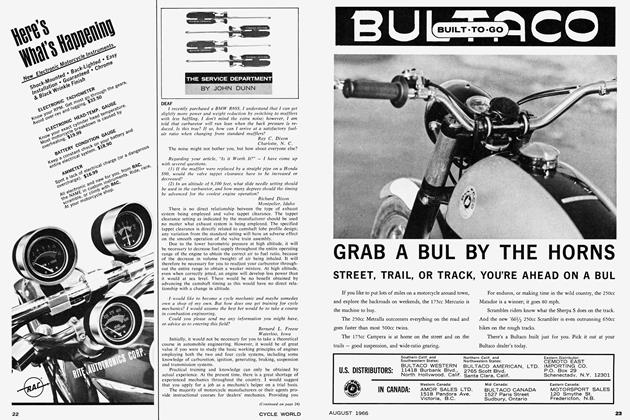

ACROSS THE POND

PART TWO

Readers were given an honest, introspective accounting of competitive racing at its spine-tingling best in the first installment of this two-part series, beginning with the 1965 Daytona Meet, and ending with the Isle of Man TT.

Mike Duff, author of the series, is a Canadian who reached a high point in his international road racing career when he was given the assignment of factory rider for Yamaha. In this second and final installment, Mike relates events which netted him second place in the 1965 World’s Championship. — Ed.

THE FOLLOWING SUNDAY was a meeting at Mallory Park in England, so no time was wasted in leaving the Island. I had entered the 250, 350 and 500 classes at Mallory and it proved to be a busy day. With only four laps practice for each machine, the bikes must be right beforehand; but the 250 (without mechanics) was not going well in practice. However, during the race, by changing my riding technique, I managed to work my way up to third place behind Read and Dave Simmonds, with the lap record to my credit.

In the 350 race, Joe Dunphy and I had a very enjoyable scrap for third place, which eventually went to Joe. While I was lying 4th in the 500 event, my mount lost a cotter-pin from the gear change mechanism of the six-speed gearbox. I retired, stuck in third gear.

Practice for the Dutch TT began Wednesday, June 23rd. Monday, we returned the 250 to Yamaha’s London agency, spent the night in the house trailer in a park near the Dover docks, then boarded the Bad Ship Fabiola on Tuesday for Ostende, Belgium. We hoped to get to Assen, Holland, scene of the Dutch TT, as soon as possible, in order to get a good vantage point in the paddock.

The Dutch TT circuit, a specially-built 4Vi mile circuit, is incorporated into the public road for this one race a year. When there is no racing, the circuit can be used for public transport, but since it leads nowhere, there is no point in using it. The paddock area is complete with hot and cold running water and showers. It is always hot at Assen during the TT week, and the order of the day is camping.

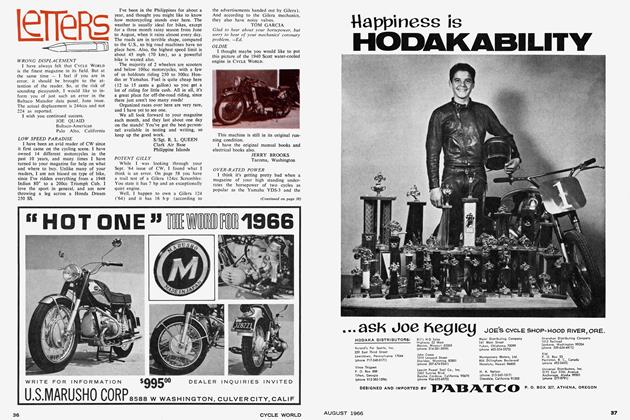

Unlike the Dutch car Grand Prix at Zandvoort, Assen’s TT attracts an excellent crowd of about 200,000 on race day. The crowd starts to gather by midnight, and by the time morning arrives, the noise is so intense, even my wife can’t sleep. Racing started at 11 a.m. The 250 race was another runaway win for Phil Read, his fifth Grand Prix win of the year, with Redman, second and myself, third. The 125 race, immediately following the 250, appeared to be another win for Read, as he had a 17-second lead over the second man, three laps from the end. Second place was a battle royal between Bill Ivy, Hugh Anderson, Katayama, Luigi Taveri and myself. Taveri retired with engine trouble, Ivy slowly dropped behind, but the battle was still fierce between the remaining three.

Near the end of the second last lap, to my surprise, we almost ran into another Yamaha that proved to be Read’s. Our. battle was now for first place. With new inspiration, I quickly tried to devise some sort of plan. The two Suzukis were a little quicker in acceleration, but the Yamaha was better at the top end. Leaving the last hairpin, I was still leading, but I could feel a rider coming up close. I moved over slightly, getting in Katayama’s way, forcing him to slow, giving myself a slight advantage. Up four gears and into the next right, up two more and into a fast right, left, back two gears for a tighter left. Oops — almost hit the straw bales, I thought. Only one more comer now. Can I do this without shutting off? We’ll soon see . . .

Then, up two more gears and, yes, I can make this corner. I only needed a foot of grass verge, and now, only 100 yards were left. I let the engine buzz — 14,800 — wow!

A cheer from the Yamaha pit and the race was won. Needless to say, champagne was the order at our table at Saturday evening’s prize giving.

All through practice, tension builds up and up, practice times get quicker and quicker, and by race day, nerves are so tight the air seems electrified. It’s like a Saturday night poker game, when the stakes are high. Prize givings are the weekly relief valve. Races are won or lost, the worry and tension finished for another week, and I want to tell you, we really raise you-know-what. Most organizers take out special insurance against damage. The Dutch prize giving is undoubtedly one of the best, and most riders spend all day Sunday getting over it.

Monday was clearout day and we joined forces with Jack Ahearn and family for a day’s hike down to Francorchamps, Belgium, scene of the following week’s Belgian Grand Prix. Practice was Thursday, Friday and Saturday, with the race on Sunday. Here, we were riding the 250s only; as there was no class for the 125, the little 125s had been sent back to Japan. In 1964 I had won the 250 race with a lap record of more than 120 mph, but Redman’s Honda literally trounced the Yamaha camp, as well as race and lap records, with Read, second, myself, third.

MIKE DUFF

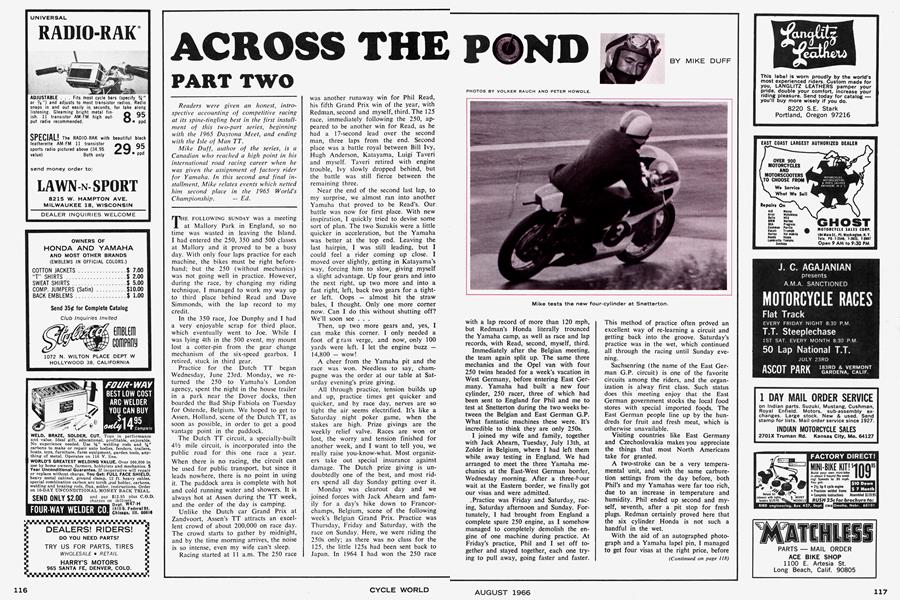

Immediately after the Belgian meeting, the team again split up. The same three mechanics and the Opel van with four 250 twins headed for a week’s vacation in West Germany, before entering East Germany. Yamaha had built a new four cylinder, 250 racer, three of which had been sent to England for Phil and me to test at Snetterton during the two weeks between the Belgian and East German G.P. What fantastic machines these were. It’s incredible to think they are only 250s.

I joined my wife and family, together with Jack Aheam, Tuesday, July 13th, at Zolder in Belgium, where I had left them while away testing in England. We had arranged to meet the three Yamaha mechanics at the East-West German border, Wednesday morning. After a three-hour wait at the Eastern border, we finally got our visas and were admitted.

.Practice was Friday and Saturday, racing, Saturday afternoon and Sunday. Fortunately, I had brought from England a complete spare 250 engine, as I somehow managed to completely demolish the engine of one machine during practice. At Friday’s practice, Phil and I set off together and stayed together, each one trying to pull away, going faster and faster. This method of practice often proved an excellent way of re-learning a circuit and getting back into the groove. Saturday’s practice was in the wet, which continued all through the racing until Sunday evening.

Sachsenring (the name of the East German G.P. circuit) is one of the favorite circuits among the riders, and the organization is alway first class. Such status does this meeting enjoy that the East German government stocks the local food stores with special imported foods. The East German people line up by the hundreds for fruit and fresh meat, which is otherwise unavailable.

Visiting countries like East Germany and Czechoslovakia makes you appreciate the things that most North Americans take for granted.

A two-stroke can be a very temperamental unit, and with the same carburetion settings from the day before, both Phil’s and my Yamahas were far too rich, due to an increase in temperature and humidity. Phil ended up second and myself, seventh, after a pit stop for fresh plugs. Redman certainly proved here that the six cylinder Honda is not such a handful in the wet.

With the aid of an autographed photograph and a Yamaha lapel pin, I managed to get four visas at the right price, before entering Czechoslovakia for the following week’s Czech Grand Prix at Brno. This was the first year the Brno circuit had world championship status, and it proved to be one of the finest meetings of the year. With a paid admission of 450,000 spectators, the expense of repaving the 12-mile circuit and building a new pit and paddock area with camping facilities, proved to be a well-warranted investment by the Czech government.

(Continued on page 118)

After an overnight delay to fix a worn fuel pump, we arrived in Brno early Wednesday morning. We checked into one of the most fabulous hotels I have ever seen, and proceeded to learn the difficult 12mile circuit. I spent all day Wednesday with pad and pencil, and only did one lap; but I’d memorized everything down to the position of each sewer, lamp post and front door step. The extra time spent on the circuit certainly paid off, as practice times were very promising.

From the start, Redman’s Honda 6 streaked away, with myself in his slipstream. At the end of lap one, Redman and I were together some five seconds ahead of third man, Read.

Read eventually caught us, and the two Yamahas slowly pulled away, until by the end, we were some 30 seconds in front. Read already had five championship wins to his credit and needed two more to guarantee the championship for Yamaha and himself. This was the only meeting of the year that I could have won, but bowed out to help Yamaha win the championship. However, there was consolation in being credited with the lap record, so the day was a great success, and Yamaha’s beating at the two previous Grands Prix was finally avenged.

That evening’s prize giving was tame (too luxurious a hotel, I suppose), but the evening was saved by Czechoslovakian champion Frank Stastny, and a visit to some of his personal friends who had a private wine cellar. I know not to this day how we got back to the hotel.

As scenic a country as Czechoslovakia is, it was a relief to leave it. At the last passport checkpoint, a strange feeling befell me, for disappearing over the hills to the horizon on my left and right, were two 20-feet-high electrified barbed wire fences, separated by 15 feet of “no man’s land.” Inside — the communistic way of life; outside — Austria and freedom.

Our next meeting was the Ulster Grand Prix on the outskirts of Belfast, Northern Ireland, two weeks after the Czech G.P. It took us five days to drive back to England, and after settling my family into the usual trailer park in southern England, near Brands Hatch, I drove to London to catch a plane for Belfast.

The pre-arranged rented car was waiting, and I drove to the circuit in time for Wednesday’s practice session. Practice was held on Wednesday and Thursday, and the race, Saturday. As usual, it was wet; in fact, during the five times I’ve been to the Ulster, I don’t think I have ever seen the circuit dry.

Dundrod, as the circuit is named, is a miniature TT and is certainly a rider’s course. The surface is made of chippings and tar, which provides extremely good traction, even in the wet. With a crowd of some 50,000, despite the expected rain, racing got underway at 11 a.m. with the 350 race. Towards the end of this race, with a lead of almost two minutes, Redman struck a neutral gearing down for a slippery hairpin, and dropped his Honda, breaking his collar bone. This incident, though not serious, put “Jammy Jim” out of the 250 race. Consequently, with no serious opposition, Read romped home to his seventh Grand Prix win of the year, grabbing the 250 world title for himself and Yamaha. I was second again.

My plane left Belfast early Monday morning, putting me back home by noon.

The annual Silverstone meeting had been moved from its traditional April date back to August 14th, seven days after the Ulster, in the hope of warmer, dryer weather. Well, at least this year it was warm rain and not snow. Phil Read and I were given the same time for the 250 race, but first place was awarded to me by a tire’s width. The 350 and 500 races were won by Mike Hailwood. Riding a standard 7R AJS in the 350 race, Hailwood literally walked all over the confirmed short circuit aces and silenced the anti-Hailwood fans in typical Hailwood nonchalant fashion.

Having cinched the world title, Read decided against going to the Finnish Grand Prix at Imatra, two miles from the Russian border. Because I wanted to hang onto my second place in the championship, I borrowed two works 250s to take privately to Finland. No works mechanics were going, as the title was already won.

This time, without the house trailer, we made good time on the 1,200 mile journey. A personal friend went with us to act as mechanic. Little did I know how much work was waiting for us.

I had entered both the 250 and 350 classes. The 250 went extremely well during practice, but the 350 (254 was its actual capacity) did not go well at all. All of practice was wet and cool, but for race day, it was hot and dry. With such a sudden change in weather conditions, it was lucky that we had the correct carburetion settings for the 250 race, which I won. However, the 254 was a different story, and I only managed nine laps, before retiring with an overchoked engine (and to think we had worked all through the night to get it right). But it was the 250 race I was more concerned with as far as championship points were concerned.

Later, I found out that one of the reasons I was loaned these two machines was because the factory wanted to see if their riders were capable of maintaining these complex and delicate bikes. If not, then it seems unlikely we would have been loaned bikes in the future without works mechanics. I don’t think we did too badly with a win, lap and race records.

The following weekend was the British Championship meeting at Oulton Park, with practice on Saturday and the race, Monday. Since this was an international meeting, it was worth the expense of returning to England before the Italian Grand Prix on September 5th.

Riding the lightweight 7R, I had a terrific scrap with Derek Minter and Dan Shorey during the 350 championship, which eventually went to Shorey, with myself, second and Minter, third. Read retired with engine trouble in the 250 race, leaving me to carry on to an easy win. Because I ride with a Canadian competition license, Peter Inchley, who finished second, was awarded the 250. British Championship. He was the first ACU license-holder to finish. Tom Arter, my sponsor in the 350 and 500 classes, had recently finished preparing his ex-works 500 AJS Porcupine, which I rode in the 500 championship but retired, as it insisted on jumping out of third gear, sending the revs soaring.

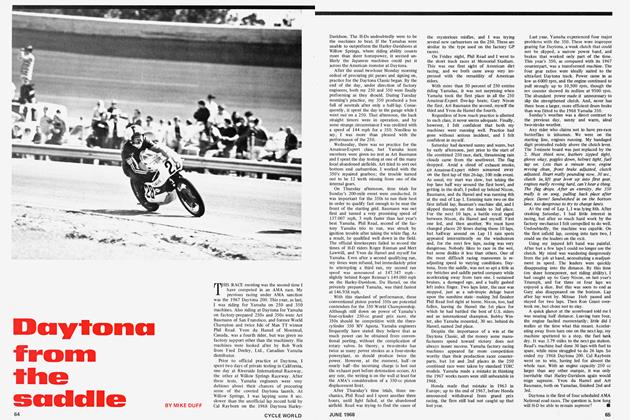

It was a bit of a rush to get to Monza, near Milan, Italy, in time for Thursday’s practice for the Italian Grand Prix. It is a two-day drive under the best of conditions, and we arrived at the San Austorgio Hotel in Arcore (home of the famous Güera factory) late Wednesday evening. Yamaha had sent over two works mechanics and one of the new water-cooled four-cylinder 250s, the idea being to try to sort the new four out before the allimportant Japanese Grand Prix. Read was to ride the four, and I, the old reliable twin. Read was fastest in practice, chopping some 5 seconds off the 250 lap record, only VA seconds slower than the absolute motorcycle lap record (not bad for a 250).

(Continued, on page 120)

Even sunny Italy has its off days, and I don’t think there has been a more “off’ day than it was on race day. The rain was so intense, it was difficult to see riders 100 yards away. But, fortunately, the downpour had let up slightly just before the 250 race. Both Read and I suffered with water in the machinery. I retired after 12 laps, but Read pressed on to finish seventh after three pit stops for fresh plugs.

I returned to England with the two bikes I had at Monza, to use at two short circuit meetings, Cadwell Park and Mallory Park. I’ll not elaborate, as I fell off at both meetings, when the crankshaft broke on one and the piston seized on the other — both in the wet. At Mallory, before dropping the 250, I had an opportunity to ride a most fascinating piece of machinery, the twin-cylinder 350 Paton, made by an Italian enthusiast in his home workshop. Never has a more business-like machine come from a private stable.

Before leaving for Japan a few days after Mallory, my wife and I made a quick trip to Finland during the two weeks between Cadwell and Mallory. Since Finland is my wife’s home, we had planned to spend the winter there skiing, and had rented an apartment on the eighth floor, overlooking 50 square miles of ski land.

It is eighteen hours flying time from London to Tokyo over the North Pole, via Copenhagen and Anchorage, Alaska. I was met at Tokyo and taken directly to Nagoya at 130 mph on the world’s fastest train, to meet our team manager and Phil Read, who had flown over earlier.

Yamaha had rented the Suzuka Circuit, scene of the Japanese Grand Prix, for two days of private testing. To the Japanese factories, the Japanese Grand Prix is their most important meeting of the year, because of the all-important home market. It is especially important to Yamaha, because they make so many other products besides motorcycles, such as pianos, skis, archery equipment, boats and musical instruments.

For me, the 1965 Japanese Grand Prix was shortlived, as I crashed heavily during Yamaha’s third testing period. I seriously damaged my left hip joint and spent the next 10 weeks flat on my back in a hospital in Nagoya. However, this accident in no way affected my position in the world’s championship, and I’m proud to say I maintained my second place behind Phil Read, making it 1-2 for Yamaha.

Just before Christmas, I was transferred by stretcher to another hospital in Toronto, Canada, where I underwent an operation to rebuild my hip. I’m hoping to be fit again early in the 1966 season.

So ended 1965 and the 1965 racing season; a season of mixed feelings and fortunes; a season ending with many rumors which promise to make 1966 one of the most exciting seasons since the days of full factory support of the early 1950s.