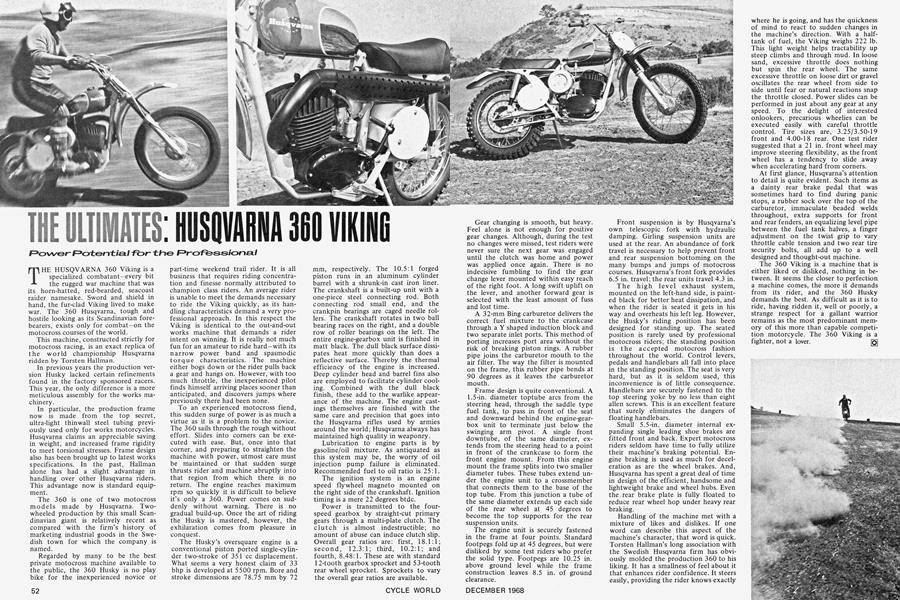

THE ULTIMATES: HUSAQVARNA 360 VIKING

Power Potential for the Professional

THE HUSQVARNA 360 Viking is a specialized combatant—every bit the rugged war machine that was its horn-hatted, red-bearded, seacoast raider namesake. Sword and shield in hand, the fur-clad Viking lived to make war. The 360 Husqvarna, tough and hostile looking as its Scandinavian fore-bearers, exists only for combat—on the motocross courses of the world.

This machine, constructed strictly for motocross racing, is an exact replica of the world championship Husqvarna ridden by Torsten Hallman.

In previous years the production version Husky lacked certain refinements found in the factory sponsored racers. This year, the only difference is a more meticulous assembly for the works machinery.

In particular, the production frame now is made from the top secret, ultra-light thinwall steel tubing previously used only for works motorcycles. Husqvarna claims an appreciable saving in weight, and increased frame rigidity to meet torsional stresses. Frame design also has been brought up to latest works specifications. In the past, Hallman alone has had a slight advantage in handling over other Husqvarna riders. This advantage now is standard equipment.

The 360 is one of two motocross models made by Husqvarna. Twowheeled production by this small Scandinavian giant is relatively recent as compared with the firm’s history of marketing industrial goods in the Swedish town for which the company is named.

Regarded by many to be the best private motocross machine available to the public, the 360 Husky is no play bike for the inexperienced novice or part-time weekend trail rider. It is all business that requires riding concentration and finesse normally attributed to champion class riders. An average rider is unable to meet the demands necessary to ride the Viking quickly, as its handling characteristics demand a very professional approach. In this respect the Viking is identical to the out-and-out works machine that demands a rider intent on winning. It is really not much fun for an amateur to ride hard—with its narrow power band and spasmodic torque characteristics. The machine either bogs down or the rider pulls back a gear and hangs on. However, with too much throttle, the inexperienced pilot finds himself arriving places sooner than anticipated, and discovers jumps where previously there had been none.

To an experienced motocross fiend, this sudden surge of power is as much a virtue as it is a problem to the novice. The 360 sails through the rough without effort. Slides into corners can be executed with ease. But, once into that corner, and preparing to straighten the machine with power, utmost care must be maintained or that sudden surge thrusts rider and machine abruptly into that region from which there is no return. The engine reaches maximum rpm so quickly it is difficult to believe it’s only a 360. Power comes on suddenly without warning. There is no gradual build-up. Once the art of riding the Husky is mastered, however, the exhilaration comes from pleasure in conquest.

The Husky’s oversquare engine is a conventional piston ported single-cylinder two-stroke of 351 cc displacement. What seems a very honest claim of 33 bhp is developed at 5500 rpm. Bore and stroke dimensions are 78.75 mm by 72 mm, respectively. The 10.5:1 forged piston runs in an aluminum cylinder barrel with a shrunk-in cast iron liner. The crankshaft is a built-up unit with a one-piece steel connecting rod. Both connecting rod small, end, and the crankpin bearings are caged needle rollers. The crankshaft rotates in two ball bearing races on the right, and a double row of roller bearings on the left. The entire engine-gearbox unit is finished in matt black. The dull black surface dissipates heat more quickly than does a reflective surface. Thereby the thermal efficiency of the engine is increased. Deep cylinder head and barrel fins also are employed to facilitate cylinder cooling. Combined with the dull black finish, these add to the warlike appearance of the machine. The engine castings themselves are finished with the same care and precision that goes into the Husqvarna rifles used by armies around the world; Husqvarna always has maintained high quality in weaponry.

Lubrication to engine parts is by gasoline/oil mixture. As antiquated as this system may be, the worry of oil injection pump failure is eliminated. Recommended fuel to oil ratio is 25:1.

The ignition system is an engine speed flywheel magneto mounted on the right side of the crankshaft. Ignition timing is a mere 22 degrees btdc.

Power is transmitted to the fourspeed gearbox by straight-cut primary gears through a multi-plate clutch. The clutch is almost indestructible; no amount of abuse can induce clutch slip. Overall gear ratios are: first, 18.1:1; second, 12.3:1; third, 10.2:1; and fourth, 8.48:1. These are with standard 12-tooth gearbox sprocket and 53-tooth rear wheel sprocket. Sprockets to vary the overall gear ratios are available.

Gear changing is smooth, but heavy. Feel alone is not enough for positive gear changes. Although, during the test no changes were missed, test riders were never sure the next gear was engaged until the clutch was home and power was applied once again. There is no indecisive fumbling to find the gear change lever mounted within easy reach of the right foot. A long swift uplift on the lever, and another forward gear is selected with the least amount of fuss and lost time.

A 32-mm Bing carburetor delivers the correct fuel mixture to the crankcase through a Y shaped induction block and two separate inlet ports. This method of porting increases port area without the risk of breaking piston rings. A rubber pipe joins the carburetor mouth to the air filter. The way the filter is mounted on the frame, this rubber pipe bends at 90 degrees as it leaves the carburetor mouth.

Frame design is quite conventional. A 1.5-in. diameter toptube arcs from the steering head, through the saddle type fuel tank, to pass in front of the seat and downward behind the engine-gearbox unit to terminate just below the swinging arm pivot. A single front downtube, of the same diameter, extends from the steering head to a point in front of the crankcase to form the front engine mount. From this engine mount the frame splits into two smaller diameter tubes. These tubes extend under the engine unit to a crossmember that connects them to the base of the top tube. From this junction a tube of the same diameter extends up each side of the rear wheel at 45 degrees to become the top supports for the rear suspension units.

The engine unit is securely fastened in the frame at four points. Standard footpegs fold up at 45 degrees, but were disliked by some test riders who prefer the solid type. Footpegs are 10.25 in. above ground level while the frame construction leaves 8.5 in. of ground clearance.

Front suspension is by Husqvarna’s own telescopic fork with hydraulic damping. Girling suspension units are used at the rear. An abundance of fork travel is necessary to help prevent front and rear suspension bottoming on the many bumps and jumps of motocross courses. Husqvarna’s front fork provides 6.5 in. travel; the rear units travel 4.3 in.

The high level exhaust system, mounted on the left-hand side, is painted black for better heat dissipation, and when the rider is seated it gets in his way and overheats his left leg. However, the Husky’s riding position has been designed for standing up. The seated position is rarely used by professional motocross riders; the standing position is the accepted motocross fashion throughout the world. Control levers, pedals and handlebars all fall into place in the standing position. The seat is very hard, but as it is seldom used, this inconvenience is of little consequence. Handlebars are securely fastened to the top steering yoke by no less than eight alien screws. This is an excellent feature that surely eliminates the dangers of floating handlebars.

Small 5.5-in. diameter internal expanding single leading shoe brakes are fitted front and back. Expert motocross riders seldom have time to fully utilize their machine’s braking potential. Engine braking is used as much for deceleration as are the wheel brakes. And, Husqvarna has spent a great deal of time in design of the efficient, handsome and lightweight brake and wheel hubs. Even the rear brake plate is fully floated to reduce rear wheel hop under heavy rear braking.

Handling of the machine met with a mixture of likes and dislikes. If one word can describe this aspect of the machine’s character, that word is quick. Torsten Hallman’s long association with the Swedish Husqvarna firm has obviously molded the production 360 to his liking. It has a smallness of feel about it that enhances rider confidence. It steers easily, providing the rider knows exactly where he is going, and has the quickness of mind to react to sudden changes in the machine’s direction. With a halftank of fuel, the Viking weighs 222 lb. This light weight helps tractability up steep climbs and through mud. In loose sand, excessive throttle does nothing but spin the rear wheel. The same excessive throttle on loose dirt or gravel oscillates the rear wheel from side to side until fear or natural reactions snap the throttle closed. Power slides can be performed in just about any gear at any speed. To the delight of interested onlookers, precarious wheelies can be executed easily with careful throttle control. Tire sizes are, 3.25/3.50-19 front and 4.00-18 rear. One test rider suggested that a 21 in. front wheel may improve steering flexibility, as the front wheel has a tendency to slide away when accelerating hard from corners.

At first glance, Husqvarna’s attention to detail is quite evident. Such items as a dainty rear brake pedal that was sometimes hard to find during panic stops, a rubber sock over the top of the carburetor, immaculate beaded welds throughout, extra supports for front and rear fenders, an equalizing level pipe between the fuel tank halves, a finger adjustment on the twist grip to vary throttle cable tension and two rear tire security bolts, all add up to a well designed and thought-out machine.

The 360 Viking is a machine that is either liked or disliked, nothing in between. It seems the closer to perfection a machine comes, the more it demands from its rider, and the 360 Husky demands the best. As difficult as it is to ride, having ridden it, well or poorly, a strange respect for a gallant warrior remains as the most predominant memory of this more than capable competition motorcycle. The 360 Viking is a fighter, not a lover. [Ö]