THOMAS FIRTH JONES

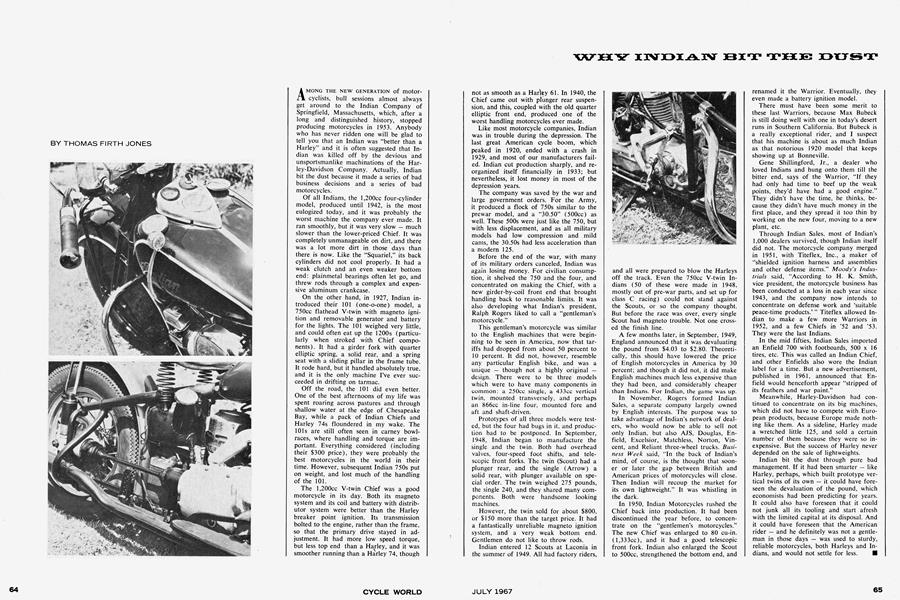

AMONG THE NEW GENERATION of motorcyclists, bull sessions almost always get around to the Indian Company of Springfield, Massachusetts, which, after a long and distinguished history, stopped producing motorcycles in 1953. Anybody who has never ridden one will be glad to tell you that an Indian was “better than a Harley” and it is often suggested that Indian was killed off by the devious and unsportsmanlike machinations of the Harley-Davidson Company. Actually, Indian bit the dust because it made a series of bad business decisions and a series of bad motorcycles.

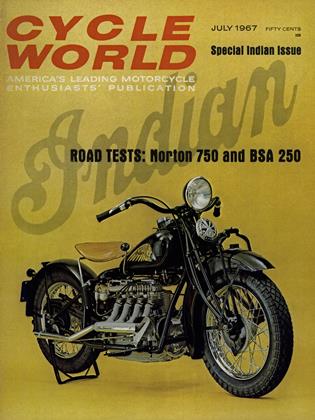

Of all Indians, the l,200cc four-cylinder model, produced until 1942, is the most eulogized today, and it was probably the worst machine the company ever made. ran smoothly, but it was very slow — much slower than the lower-priced Chief. It was completely unmanageable on dirt, and there was a lot more dirt in those days than there is now. Like the “Squariel,” its back cylinders did not cool properly. It had weak clutch and an even weaker bottom end: plainmetal bearings often let go, and threw rods through a complex and expensive aluminum crankcase.

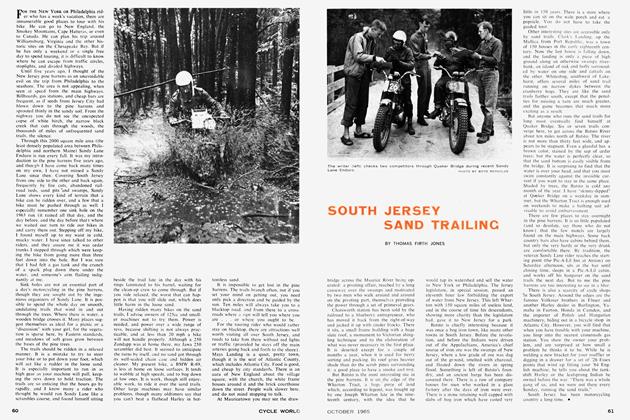

On the other hand, in 1927, Indian introduced their 101 (one-o-one) model, 750cc flathead V-twin with magneto ignition and removable generator and battery for the lights. The 101 weighed very little, and could often eat up the 1200s (particularly when stroked with Chief components). It had a girder fork with quarter elliptic spring, a solid rear, and a spring seat with a sliding pillar in the frame tube. It rode hard, but it handled absolutely true, and it is the only machine I’ve ever succeeded in drifting on tarmac.

Off the road, the 101 did even better. One of the best afternoons of my life was spent roaring across pastures and through shallow water at the edge of Chesapeake Bay, while a pack of Indian Chiefs and Harley 74s floundered in my wake. The 101s are still often seen in carney bowlraces, where handling and torque are important. Everything considered (including their $300 price), they were probably the best motorcycles in the world in their time. However, subsequent Indian 750s put on weight, and lost much of the handling of the 101.

The l,200cc V-twin Chief was a good motorcycle in its day. Both its magneto system and its coil and battery with distributor system were better than the Harley breaker point ignition. Its transmission bolted to the engine, rather than the frame, so that the primary drive stayed in adjustment. It had more low speed torque, but less top end than a Harley, and it was smoother running than a Harley 74, though not as smooth as a Harley 61. In 1940, the Chief came out with plunger rear suspension, and this, coupled with the old quarter elliptic front end, produced one of the worst handling motorcycles ever made.

WHY INDIAN BIT THE DUST

Like most motorcycle companies, Indian was in trouble during the depression. The last great American cycle boom, which peaked in 1920, ended with a crash in 1929, and most of our manufacturers failed. Indian cut production sharply, and reorganized itself financially in 1933; but nevertheless, it lost money in most of the depression years.

The company was saved by the war and large government orders. For the Army, it produced a flock of 750s similar to the prewar model, and a “30.50” (500cc) as well. These 500s were just like the 750, but with less displacement, and as all military models had low compression and mild cams, the 30.50s had less acceleration than a modern 125.

Before the end of the war, with many of its military orders canceled, Indian was again losing money. For civilian consumption, it shelved the 750 and the four, and concentrated on making the Chief, with a new girder-by-coil front end that brought handling back to reasonable limits. It was also developing what Indian’s president, Ralph Rogers liked to call a “gentleman’s motorcycle.”

This gentleman’s motorcycle was similar to the English machines that were beginning to be seen in America, now that tariffs had dropped from about 50 percent to 10 percent. It did not, however, resemble any particular English bike, and was a unique — though not a highly original — design. There were to be three models which were to have many components in common: a 250cc single, a 433cc vertical twin, mounted transversely, and perhaps an 866cc in-line four, mounted fore and aft and shaft-driven.

Prototypes of all three models were tested, but the four had bugs in it, and production had to be postponed. In September, 1948, Indian began to manufacture the single and the twin. Both had overhead valves, four-speed foot shifts, and telescopic front forks. The twin (Scout) had a plunger rear, and the single (Arrow) a solid rear, with plunger available on special order. The twin weighed 275 pounds, the single 240, and they shared many components. Both were handsome looking machines.

However, the twin sold for about $800, or $150 more than the target price. It had a fantastically unreliable magneto ignition system, and a very weak bottom end. Gentlemen do not like to throw rods.

Indian entered 12 Scouts at Laconia in the summer of 1949. All had factory riders, and all were prepared to blow the Harleys off the track. Even the 750cc V-twin Indians (50 of these were made in 1948, mostly out of pre-war parts, and set up for class C racing) could not stand against the Scouts, or so the company thought. But before the race was over, every single Scout had magneto trouble. Not one crossed the finish line.

A few months later, in September, 1949, England announced that it was devaluating the pound from $4.03 to $2.80. Theoretically, this should have lowered the price of English motorcycles in America by 30 percent; and though it did not, it did make English machines much less expensive than they had been, and considerably cheaper than Indians. For Indian, the game was up.

In November, Rogers formed Indian Sales, a separate company largely owned by English interests. The purpose was to take advantage of Indian’s network of dealers, who would now be able to sell not only Indian, but also AJS, Douglas, Enfield, Excelsior, Matchless, Norton, Vincent, and Reliant three-wheel trucks. Business Week said, “In the back of Indian’s mind, of course, is the thought that sooner or later the gap between British and American prices of motorcycles will close. Then Indian will recoup the market for its own lightweight.” It was whistling in the dark.

In 1950, Indian Motorcycles rushed the Chief back into production. It had been discontinued the year before, to concentrate on the “gentlemen’s motorcycles.” The new Chief was enlarged to 80 cu-in. (l,333cc), and it had a good telescopic front fork. Indian also enlarged the Scout to 500cc, strengthened the bottom end, and renamed it the Warrior. Eventually, they even made a battery ignition model.

There must have been some merit to these last Warriors, because Max Bubeck is still doing well with one in today’s desert runs in Southern California. But Bubeck is a really exceptional rider, and I suspect that his machine is about as much Indian as that notorious 1920 model that keeps showing up at Bonneville.

Gene Shillingford, Jr., a dealer who loved Indians and hung onto them till the bitter end, says of the Warrior, “If they had only had time to beef up the weak points, they’d have had a good engine.” They didn’t have the time, he thinks, because they didn’t have much money in the first place, and they spread it too thin by working on the new four, moving to a new plant, etc.

Through Indian Sales, most of Indian’s 1,000 dealers survived, though Indian itself did not. The motorcycle company merged in 1951, with Titeflex, Inc., a maker of “shielded ignition harness and assemblies and other defense items.” Moody’s Industrials said, “According to H. K. Smith, vice president, the motorcycle business has been conducted at a loss in each year since 1943, and the company now intends to concentrate on defense work and ‘suitable peace-time products.’ ” Titeflex allowed Indian to make a few more Warriors in 1952, and a few Chiefs in ’52 and ’53. They were the last Indians.

In the mid fifties, Indian Sales imported an Enfield 700 with footboards, 500 x 16 tires, etc. This was called an Indian Chief, and other Enfields also wore the Indian label for a time. But a new advertisement, published in 1961, announced that Enfield would henceforth appear “stripped of its feathers and war paint.”

Meanwhile, Harley-Davidson had continued to concentrate on its big machines, which did not have to compete with European products, because Europe made nothing like them. As a sideline, Harley made a wretched little 125, and sold a certain number of them because they were so inexpensive. But the success of Harley never depended on the sale of lightweights.

Indian bit the dust through pure bad management. If it had been smarter — like Harley, perhaps, which built prototype vertical twins of its own — it could have foreseen the devaluation of the pound, which economists had been predicting for years. It could also have foreseen that it could not junk all its tooling and start afresh with the limited capital at its disposal. And it could have foreseen that the American rider — and he definitely was not a gentleman in those days — was used to sturdy, reliable motorcycles, both Harleys and Indians, and would not settle for less. ■