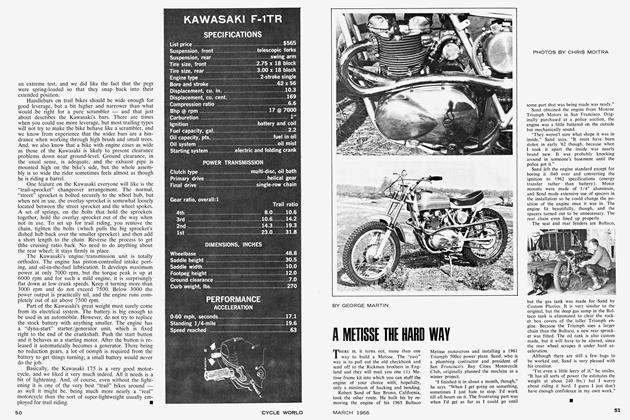

ENDURO MECHINERY

HOW THE EXPERTS DO IT.

THOMAS FIRTH JONES

AN ENDURO IS LIKE A sports car rally in that it is run for several hours — or days — over a course that does not repeat itself, and the winner is the rider who keeps closest to an official average speed. Two riders start every minute, and each is credited with 1,000 points. You lose one point for each minute late and two points for each minute early at each checking station. However, unlike a rally, an enduro course is plainly marked, and the speed is easy to figure in your head (20 mph = 1 mile every 3 minutes, 24 mph = 2 miles every 5 minutes). And an enduro is run over rough country, which makes it a test of riding skill, not map reading and mathematical calculation. No slide rules nor rally stripes are used.

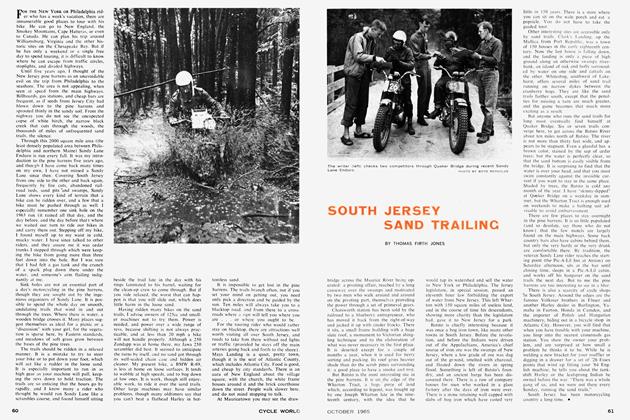

Originally, there was only one national enduro, a 500-miler; but now the AMA awards national points for 100, 125, 150, 200, 250, and 500-mile runs. Typically, the organizers will lay out a course with alternate rough and easy sections. The easy sections will be dirt roads or trails, and the rough sections may be swamps, gravel pits, briar patches, railroad trestles, boulder fields, rivers, etc. Obviously, you must make up in one section for the time you have lost in another. Most enduros are held in the fall, but a winter run, with a foot or two of snow on the ground and ice in the streams, can be pretty interesting.

To judge from the locations of the nationals, enduros are more popular in the East than in the West. Perhaps this is because, with land so much more divided up and controlled, it is harder for Eastern riders to do a little trailing on their own. Enduro requirements are so specialized that several companies manufacture machines for this purpose alone. The necessities are: a tough frame and suspension, high ground clearance, knobby tires, and a reliable engine. Usually, the engine is made reliable by detuning it and lowering the horsepower. The BSA 350 Enduro Star, which advertises “special compression and camshaft,” has considerably lower compression and milder cam than the road model. And it wins.

A detuned engine (especially one set up by the factory, rather than a stock engine with seven head gaskets) pulls well through a wide power range, and is used with a wide-ratio four speed gearbox. More than four speeds are not good, because enduros are full of surprises (though the organizers do try to avoid mine shafts and quicksand), and there is often not time to shift once, let alone two or three times.

In addition to BSA, both Bultaco and Maico make enduro machines. They look like scramblers, but are usually heavier, more durable, and less powerful. Many of the smaller English companies make “Trials” machines, which are well suited to enduros as well, and many continental firms, such as Puch and Zundapp, make lovely “Six Days Trial” machines, which would be ideal if you could get your hands on them. Only Jawa sells them across the counter. And there are the trail bikes, which are good too, if they have enough power to lug through sand and then hit fifty or sixty in the open sections.

If you cannot afford to buy an enduro machine, you can do quite a lot with conversion. A scrambler is generally not suitable, because it can be too fragile and too finicky. You may be better off starting with a standard roadster, provided it has a frame that will take the pounding.

Remove all excess metal. Lights are not needed on most runs, though a speedometer is. Crash bars, passenger pegs, etc., will do no good. However, weight is not the only consideration, and an enduro machine never looks as stripped as a scrambler. Fenders keep debris out of the moving parts, and should be retained or made even larger. An air cleaner is essential. So is a muffler, because part of every run is over public roads, and the rules require it. A high pipe, which looks very sporty, is generally not worth the trouble, unless you want to keep your road pipes from being bashed. Remove the chain case at your own peril: it weighs very little, and can save a lot of time in chain repairs.

A skid plate should be fitted, particularly to machines with horizontal cylinders and backbone frames. Springs must be stiffened, either by replacing them or else by topping up with very heavy oil. A hard riding machine is less tiring in rough country, because you don’t have to fight for control of it so much. Ground clearance can sometimes be increased by installing larger diameter wheels; but be sure they do not rub when the suspension bottoms, because it will bottom. Aluminum rims must be replaced with steel.

Do not try to modify the frame by increasing fork rake, lengthening the wheelbase, etc., unless you have a very good idea of what you’re doing. John Penton put BSA forks on his BMW 250 and cleaned house in the enduro circuit, but you may not know as much about steering geometry as he does. High speed wobbles and tail wagging can be the result of your attempts to out-guess the factory engineers.

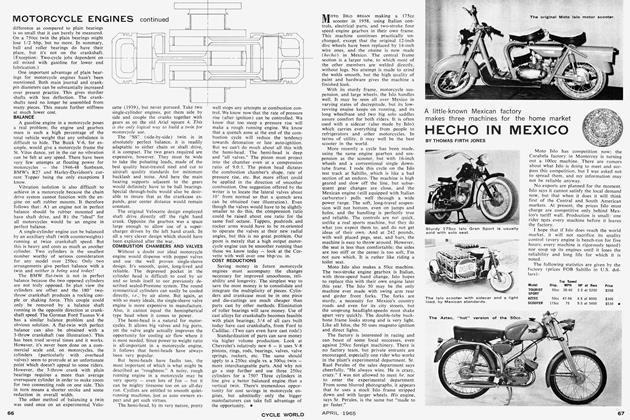

With these modifications, you have made a roadster as much like a factory enduro machine as possible. There remain further modifications, which are more individual, but which most enduro riders do make. Bars, seat, and pegs must be comfortable for a four to ten hour ride. Remember that you will be sitting upright, or standing on the pegs, or footing it through, but hardly ever will you be in a racing crouch. Wide bars give leverage in the rough, but with narrow bars your hands get whacked by branches less often. A compromise width is usually chosen, with a moderate rise, and cross braced.

Folding pegs, though seldom fitted to European trials bikes, will save many bruises. One rider told me, “After my foot caught on that stump and twisted around under the (rigid) peg, it hurt so much that I rode on for half an hour before I dared to look at it.” Safety is also promoted by ball-end levers, which can keep you and your competitors from being gouged. Gearshifts are sometimes rigged up to be operated by either foot.

Waterproof the engine with good plug covers and grommeting. A length of inner tube is sometimes slipped over the magneto or distributor and the high tension leads. Do not seal your electrical systems with goo; condensation can short out contact breaker points just as easily as swamp muck can. Nuts that tend to work loose should be drilled and cottered or smeared with locking compound.

Inner tubing is also used to enlarge the back fender, spreading from one rear frame member to the other, thus protecting the engine from water and mud. A flap of tubing extends the front fender, though it drags on the tire and looks like the tongue of a tired dog. Small pieces of tubing tied to the bars protect the controls from brush, though a better system is a piece of small diameter pipe, contoured like the bars and mounted a few inches in front of them on windshield brackets.

Instrumentation is a very individual matter. The novice enduro rider will seldom need any, because he must ride to the limit of his ability to keep from falling an hour behind and being disqualified. The experienced rider, who finds himself getting ahead of schedule in some sections, usually mounts a large and accurate speedometer with trip odometer. He carries a pocket watch, which may be mounted on the bars, hung on a string around his neck, or strapped to the inside of his forearm.

He usually mounts his route sheet — a printed guide to all turns and the distances between them — somewhere in easy view. It may be taped to the tank or to a revolving drum made out of a tin can and mounted on the handlebars. Then there are the magnifying lenses which are mounted above the drums, and the riders who transcribe the route sheets onto adding machine paper mounted on two small drums, like a Chinese scroll. These seem unnecessarily complicated, particularly as all turns are marked with signs on trees, and only defacement of the signs by outsiders or getting lost should make it necessary to look at the route sheet at all. I generally stuff my route sheet into an inside pocket, to be used in disasters only, along with the chocolate bars.

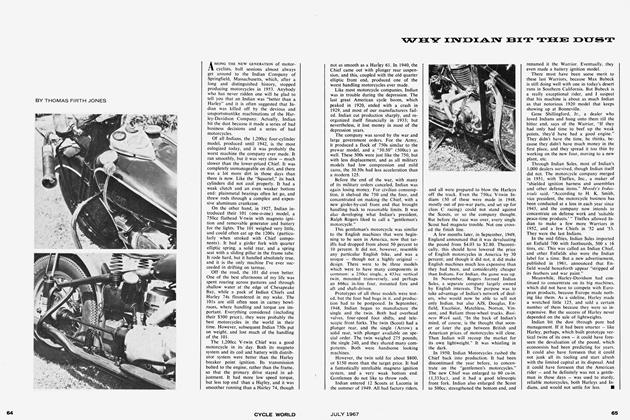

A helmet is required for all AMA sanctioned enduros. Leather gloves are almost equally necessary, no matter how hot the weather, and some riders glue foam rubber pads across the knuckles of leather mittens. A suit of comfortable leather is the best protection against brush and spills, but coveralls, denims and Barbour suits are worn too. Boots are a must, and the higher the better to protect your legs from rocks and brush. Goggles and face shields of many varieties are used, and about half of them survive a day’s running. In general, the novice rider has the least equipment, and needs it the most.

Tools should be carried, because you have an hour before you are disqualified, and quite a few repairs can be made in that time. The complete factory tool kit is best, if your machine still has one. It is better carried on the machine than on you, because it is less annoying and less likely to get lost. Larger tools, such as long screwdrivers and vicegrips, are often taped to the frame. A few riders like to tie a coil of rope on, though it is hard to say whether this classifies as tools or parts.

Some parts definitely should be carried. General practice is to carry a spare of the part that busted and put you out of the running last time. In addition to this, you should have some baling wire, spark plugs, small electrical parts, master links, and a chain breaker. Many riders carry extra shift and brake levers, as these are likely to be hit by rocks and logs, and a spare cable or two, even though the operating cables are taped down to the forks. Jawa “Six Days Trial” machines are equipped with tube patching kits and compressed air bottles, but where their riders find time to change tires is a mystery. Whatever you take, tie or tape down as much as possible in places where it won’t be in your way and you won’t have to think about it till you need it.

Riding in enduros should be less discouraging than exploring trails on your own, because you know that at least one and perhaps a hundred riders have been over this section ahead of you today, and it is therefore theoretically possible to get through. On well marked enduros, a particularly tricky section will have warning signs. Unless the pressure to keep up to the minute overcomes you, you should be able to finish the day. Remember that an enduro tests the endurance of three things: your machine, your body, and your wits. Only one has to fail to keep you from reaching the finish line. ■