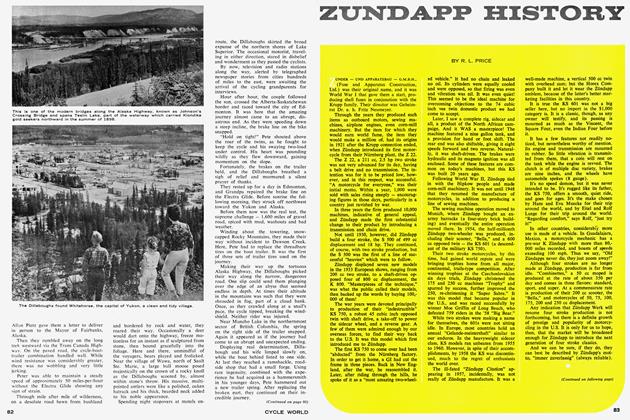

NORTH TO CANADA

TOURING

R. L. PRICE

GEORGE PUT NEW TIRES on front and rear. My rear tire was only a month old, so I put a new one on the front only. We waterproofed the tent the day before and left it pitched in the backyard to dry. My heavy-duty, thermal underwear had just arrived by mail that week, and George was to pick his up on our way through Oakland. Finally, everything was packed in waterproof luggage and strapped to our respective machines. Since the rainforest of the Olympic Peninsula was on the itinerary, avoiding bad weather was beyond our fondest hopes.

The general route was to be north along the Pacific Coast to the western end of the Trans-Canada Highway, then East to the Canadian Rockies and South along the Continental Divide. Except for side trips, it went fairly well as planned. Our only rule was to avoid any area in which there was not another road out. To keep a close watch on the temperature, I mounted a thermometer on the upper fork support and noticed it indicated 63° as we aimed our opposed twins North to Canada.

There are certainly warmer places to go in the Fall than Canada, but there are none prettier, and where else can you see all the trees turning every shade nature can provide or catch a glimpse of the invigorating weather that is still months away from the Southland? Too, autumn finds highways nearly barren, parks and resorts deserted. The choicest accommodations are yours at nearly every stop.

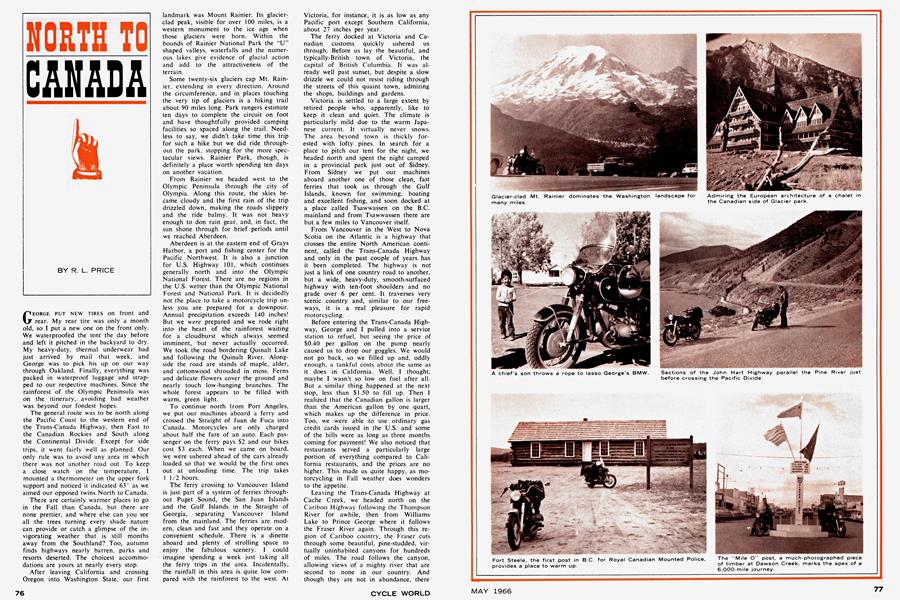

After leaving California and crossing Oregon into Washington State, our first landmark was Mount Rainier. Its glacierclad peak, visible for over 100 miles, is a western monument to the ice age when those glaciers were born. Within the bounds of Rainier National Park the "U" shaped valleys, waterfalls and the numerous lakes give evidence of glacial action and add to the attractiveness of the terrain.

Some twenty-six glaciers cap Mt. Rainier, extending in every direction. Around the circumference, and in places touching the very tip of glaciers is a hiking trail about 90 miles long. Park rangers estimate ten days to complete the circuit on foot and have thoughtfully provided camping facilities so spaced along the trail. Needless to say, we didn't take time this trip for such a hike but we did ride throughout the park, stopping for the more spectacular views. Rainier Park, though, is definitely a place worth spending ten days on another vacation.

From Rainier we headed west to the Olympic Peninsula through the city of Olympia. Along this route, the skies became cloudy and the first rain of the trip drizzled down, making the roads slippery and the ride balmy. It was not heavy enough to don rain gear, and, in fact, the sun shone through for brief periods until we reached Aberdeen.

Aberdeen is at the eastern end of Grays Harbor, a port and fishing center for the Pacific Northwest. It is also a junction for U.S. Highway 101, which continues generally north and into the Olympic National Forest. There are no regions in the U.S. wetter than the Olympic National Forest and National Park. It is decidedly not the place to take a motorcycle trip unless you are prepared for a downpour. Annual precipitation exceeds 140 inches! But we were prepared and we rode right into the heart of the rainforest waiting for a cloudburst which always seemed imminent, but never actually occurred. We took the road bordering Quinalt Lake and following the Quinalt River. Alongside the road are stands of maple, alder, and cottonwood shrouded in moss. Ferns and delicate flowers cover the ground and nearly touch low-hanging branches. The whole forest appears to be filled with warm, green light.

To continue north lrom Port Angeles, we put our machines aboard a ferry and crossed the Straight of Juan de Fuca into Canada. Motorcycles are only charged about half the fare of an auto. Each passenger on the ferry pays $2 and our bikes cost S3 each. When we came on board, we were ushered ahead of the cars already loaded so that we would be the first ones out at unloading time. The trip takes 1 1/2 hours.

The ferry crossing to Vancouver Island is just part of a system of ferries throughout Puget Sound, the San Juan Islands and the Gulf Islands in the Straight of Georgia, separating Vancouver Island from the mainland. The ferries are modern, clean and fast and they operate on a convenient schedule. There is a dinette aboard and plenty of strolling space to enjoy the fabulous scenery. I could imagine spending a week just taking all the ferry trips in the area. Incidentally, the rainfall in this area is quite low compared with the rainforest to the west. At Victoria, for instance, it is as low as any Pacific port except Southern California, about 27 inches per year.

The ferry docked at Victoria and Canadian customs quickly ushered us through. Before us lay the beautiful, and typically-British town of Victoria, the capital of British Columbia. It was already well past sunset, but despite a slow drizzle we could not resist riding through the streets of this quaint town, admiring the shops, buildings and gardens.

Victoria is settled to a large extent by retired people who, apparently, like to keep it clean and quiet. The climate is particularly mild due to the warm Japanese current. It virtually never snows. The area beyond town is thickly forested with lofty pines. In search for a place to pitch our tent for the night, we headed north and spent the night camped in a provincial park just out of Sidney. From Sidney we put our machines aboard another one of those clean, fast ferries that took us through the Gulf Islands, known for swimming, boating and excellent fishing, and soon docked at a place called Tsawwassen on the B.C. mainland and from Tsawwassen there are but a few miles to Vancouver itself.

From Vancouver in the West to Nova Scotia on the Atlantic is a highway that crosses the entire North American continent, called the Trans-Canada Highway and only in the past couple of years has it been completed. The highway is not just a link of one country road to another, but a wide, heavy-duty, smooth-surfaced highway with ten-foot shoulders and no grade over 6 per cent. It traverses very scenic country and, similar to our freeways, it is a real pleasure for rapid motorcycling.

Before entering the Trans-Canada Highway, George and I pulled into a service station to refuel, but seeing the price of $0.40 per gallon on the pump nearly caused us to drop our goggles. We would not go back, so we filled up and, oddly enough, a tankful costs about the same as it does in California. Well, I thought, maybe I wasn't so low on fuel after all. But a similar thing happened at the next stop, less than $1.50 to fill up. Then I realized that the Canadian gallon is larger than the American gallon by one quart, which makes up the difference in price. Too, we were able to use ordinary gas credit cards issued in the U.S. and some of the bills were as long as three months coming for payment! We also noticed that restaurants served a particularly large portion of everything compared to California restaurants, and the prices are no higher. This made us quite happy, as motorcycling in Fall weather does wonders to the appetite.

Leaving the Trans-Canada Highway at Cache Creek, we headed north on the Cariboo Highway following the Thompson River for awhile, then from Williams Lake to Prince George where it follows the Fraser River again. Through this region of Cariboo country, the Fraser cuts through some beautiful, pine-studded, virtually uninhabited canyons for hundreds of miles. The road follows the canyon, allowing views of a mighty river that are second to none in our country. And though they are not in abundance, there are a few provincial parks along the highway to accommodate overnight campers.

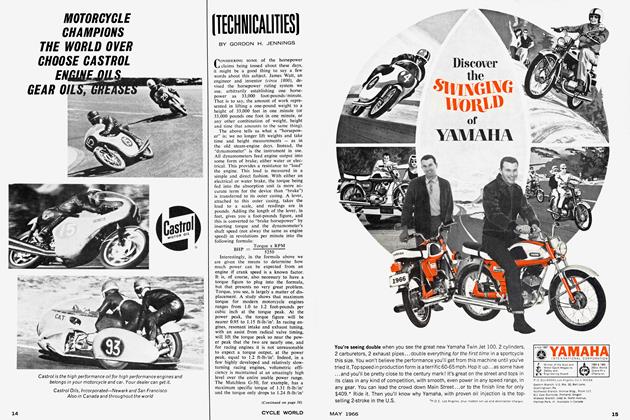

Dawson Creek marks "Mile 0" of the Alaska or "Alean" Highway. It is sometimes confused with Dawson City in the Klondike, also on the Alean, but in the Yukon Territory some 1,250 miles away. Both were named after George Mercer Dawson, who visited the area in 1879 while making a railroad survey. Before the Alean, Dawson Creek was an outpost of some 400 to 500 population. Since the Alean and with the Peace River project underway, it is a flourishing 14,000 complete with a modern department store and car agencies for nearly every make.

Probably the most-asked tourist question is: "How cold does it get?" Friendly inhabitants are quick to respond, giving actual figures that you would never find in tourist literature. Winter temperatures are commonly 35 to 40 below zero. The mercury plummets to minus 60 on occasion, they say. The Chamber of Commerce admits to a "mean monthly low average of 2 degrees," whatever that means.

About 100 miles to the north, a tremendous construction project on the Peace River is underway. It will be the largest earth-filled dam in the world and will include a power plant with more capacity than any other in the Western Hemisphere. According to the local inhabitants, the area is growing at a tremendous rate, like 11% per year.

Eventually, we reached the outskirts of Edmonton in Alberta Province and then turned due West on Route 16. Since the road was flat and traffic very light, we were able to make good time, in spite of the weather. Soon the countryside became dotted more frequently with groves of mixed evergreens and aspens, and the road began taking a few dips and turns, evidence of the hills at the foot of the Rockies.

At the entrance to Jasper Park, there is a guard post where $2 per vehicle is collected, good for several months in all Canadian national parks. The town of Jasper itself is not developed as well as Banff to the south, mainly because it is just farther away from population centers. When the road from Prince George is completed, there will, undoubtedly, be more improvement. Nevertheless, it is a pretty, alpine community situated in the Northern Rockies and Jasper Park is the largest of all the Mountain Parks. Every sort of accommodation, from wilderness camping to luxury hotels and motels is available. Surrounding Jasper are miles of scenic trails unveiling splendors that you could never see just riding your machine. For instance, there are hot springs, glacial lakes, falls and spectacular mountain ranges like The Ramparts. Here again, is an area in which one could spend a pleasurable week.

Between Jasper and Banff is 178 miles of the most scenic alpine highway to be found anywhere in the Rockies. Dozens of peaks, including Edith Cavell ( 11,053'), line both sides of the glass-smooth, blacktop highway, and numerous lakes, each one more breathtaking than the last, to the most famous, Lake Louise, are generously sprinkled along the way. We passed many glaciers, including the famous Columbian Icefield, and within one mile of its tongues, the Athabasca Glacier. Signs along the road point to the various peaks and ridges identifying them and marking their elevation, and to the lakes. Wild game is also plentiful, including moose, elk, goats and bear. Where the goats congregate, there is an observation turnout provided at the side of the highway. Elk feed by the roadside, and families of them are frequently seen, but the moose are less tame, travel alone and are only seen at a distance. We saw cow moose twice about 100 yards off the road. Signs along the road warn against feeding the bears. An entire day should be allowed for this ride if the weather is good to permit full enjoyment. However, with our luck, as we were leaving Jasper, bad weather hovered gloomily ahead and, within a few miles, we had to stop to don our rain suits. As the highway rose in elevation, the temperature dropped and the precipitation turned to snow. By the time we reached Sunwapta Pass (6,675'), both sides of the highway were blanketed with the falling snow, though it was not sticking to the pavement itself. Attempts to read the thermometer accurately were futile, because my face shield fogged so badly when I bent forward. The neighborhood of 30° was as close as I could read. The face shield collected a coating of ice which gradually impaired my vision until every 100 yards or so a wipe with the mitten was necessary to see where I was going. In spite of the weather, we maintained a pace of some 50 mph until passing the worst of it, whereupon we pulled into a campsite to eat and warm up. We brought our lunch with us, and fortunately, there was a small group of Canadian Alpinists here with a good fire already going. Needless to say, the usual questions and friendly conversation followed.

It was evening by the time we reached Banff, and after such a cold and wet ride, camping out just did not offer its usual appeal. Oddly enough, though there are multitudinous accommodations in Banff, so many were closed for the season that the rest were filled to capacity. For an aerial view of Banff and all the surrounding peaks and ranges and the Bow and Cascade River Valleys, there is a sedan lift to the peak of Sulphur Mountain, 3,000 feet above town. It takes only eight minutes to get to the top, costs $2 per adult and operates from May through October. At the peak is a "Tea House" with appetizing, though expensive, buffet offerings. The best offering is, of course, free and that is the spectacular view: over a dozen peaks higher than 8,000 feet in some five separate ranges and they were all snow-capped when we arrived. In fact, the already-threatening overcast could no longer contain its moisture and flakes of snow fluttered down followed by brief periods of sunshine, then more snow, so we went back down on the lift. It was not snowing at the lower elevations. In Banff, it just looked gloomy and threatening.

The Trans-Canada Highway intersects the road between Jasper and Banff at Lake Louise, 36 miles above Banff, then continues eastward through Calgary in Alberta Province. Wanting to maintain a mountain route, we broke our rule and headed back north, but just for 19 miles to Eisenhower Junction, then headed west over Vermillion Pass and into the Kootenay National Park. The route follows the Kootenay River to the south end of the park where a hot springs is located. There, a monstrous pool was constructed to catch the hot water, permitting outdoor bathing the year round. It surely seemed odd with us in all of our foul weather equipment standing there watching people sitting around in swim suits. There is a nominal charge to use the pool and they will rent you a swim suit if you need one. Near the springs is an excellent public camp where George and I stayed. It even had a hot shower.

(Continued on page 94)

The next morning we headed generally south on Route 95 and soon found ourselves out of mountainous country and in an area of lakes and rivers that seem to wonder which way to flow. For instance, we came upon a wide body of water called Columbia Lake. It looked more like a still river, but actually contains the headwaters of the mighty Columbia River. At this point, the little flow that occurs is north-bound for a hundred or so miles beyond Golden and Revelstoke, then southward again into the State of Washington.

Glacier National Park actually spills over the border from Montana into Alberta, Canada, where it is called Waterton-Glacier International Peace Park.

In the center of Glacier, we crossed the Continental Divide again at Logan Pass (elev. 6,664') and headed into the damp McDonald Creek Valley for the evening's campground. It was obvious from the unusual trash cans that the park had bears among its inhabitants. A little inquiring disclosed that the park also had mountain goat, moose and elk, though we didn't see any of them. To see the best of the park, it is necessary to hike and there is an abundance of foot trails in Glacier. Here, again, you could spend a week each year for several years before seeing it all. John Muir once wrote about Glacier: "Give a month at least to this precious preserve. The time will not be taken from the sum of your life. Instead of shortening, it will indefinitely lengthen it and make you truly immortal."

The park has an unusual background, too. Blackfoot Indians laid claim to the area and were so hostile to the white man that the park stayed "undiscovered" for a long time. In 1890, someone found copper ore in a creek on the western side and a rush began. Congress gave $1 1/2 million to the Blackfeet for the area before mining became unprofitable and the boom collapsed. It makes one wonder if the Indians hadn't outsmarted us after all and planted that ore. However, there is an entrance fee that I feel has recovered the $1 1/2 million in the 50-odd years that it has been a national park.

Glacier Park waters are among a few from widely separated places in North America where the pygmy whitefish lives, along with 21 other varieties of fish. George and I looked in several streams, but failed to see a whitefish, much less a pygmy. We saw trout, though, and became so engrossed in the abundance of fish in the streams that we looked in nearly every one we encountered, not only in Montana, but in Wyoming, Idaho and Utah as well. In one stream which parallels the road in Montana, we saw so many fish that George just couldn't restrain himself any longer. He threw in a line and out came the prettiest trout you ever saw. Of course, as we approached population centers, the fish were more scarce.

From Glacier, we crossed the Missouri River at Great Falls and headed for Yellowstone National Park. Here we did see elk, and bear too. In fact, a cinnamon bear crossed the road ahead of us as we pulled in, which was no threat as we were on our machines and he was walking. (Don't laugh, the Russians have a bear that rides a motorcycle!) We made camp in an area near Old Faithful Geyser and the bears paraded through the place like a bunch of volunteer firemen, only checking every garbage pail instead of fire hydrants, and every other campsite had a garbage pail! Now this was annoying, especially to a city boy like me.

I was nearly asleep the first time, protected by nothing more than my sleeping bag, when one of the beasts came traipsing by. That night, there was a motorcyclist buzzing around Yellowstone in unusual garb, thermal pajamas! I actually believe those garbage pails were designed to attract the bears.

Yellowstone was fairly disappointing, though, compared with the other parks we had visited. True, the geysers, the yellow-walled canyons of the Yellowstone River and the falls are quite unlike any other in the country. The Lower Falls of the Yellowstone River are twice as high as Niagara, for instance, and Yellowstone Lake is the largest in North America at such an elevation (7,731 ft.). The Park, however, is the oldest in the United States, and I must say, it looks it. All the facilities I saw appeared run-down and over-used, more so than any other park on our travels. We had spent a long time on the road, though, and the long miles evidently began taking their toll and could well have affected my perspective. By the time we left Yellowstone, we had seen so many parks that they began losing their attractiveness and we thought it best to head home.

The route home took us through Salt Lake City and Las Vegas. There was one canyon we rode through coming into Logan, Utah called Logan Canyon that deserves a few words. Of all the canyons we had seen, this was the prettiest and the nicest for motorcycling. The smooth blacktop paralleled a twisty creek the entire length of the canyon. Both sides were blooming with magnificent red flowers that made each curve of the road unfold a splendor befitting an artists's canvas. There is a campground along the way and I recommend that ride to anyone in the West.

On arriving home, my odometer indicated the entire journey took over 6,000 miles. I must say, it felt like I had been somewhere. I was tired. But there is something uniquely rewarding about motorcycle touring. It sets one quite apart from other tourists. I believe people can respect us for braving long distances and adverse conditions, much like they do pioneers or explorers as long as they haven't been prejudiced by some bad incidents or wild tales.

In any event, the one thing that the motorcycle does for you much more than the automobile, is to open the doors to conversation, and, I ask you, what better way is there to learn about a community or its people?