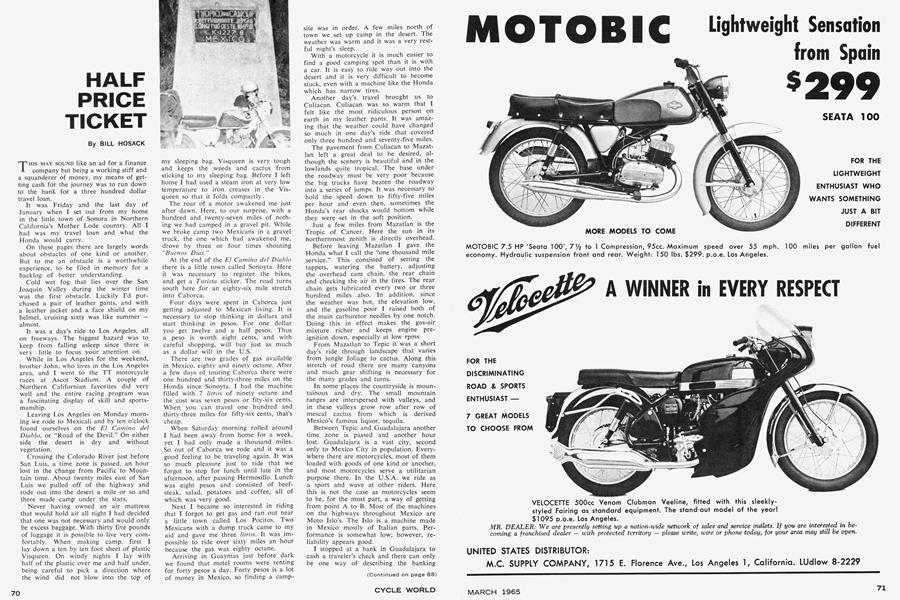

HALF PRICE TICKET

BILL HOSACK

THIS MAY SOUND like an ad for a finance company but being a working stiff and a squanderer of money, my means of getting cash for the journey was to run down to the bank for a three hundred dollar travel loan.

It was Friday and the last day of January when I set out from my home in the little town of Sonora in Northern California's Mother Lode country. All I had was my travel loan and what the Honda would carry.

On these pages there are largely words about obstacles of one kind or another. But to me an obstacle is a worthwhile experience, to be filed in memory for a backlog of better understanding.

Cold wet fog that lies over the San Joaquin Valley during the winter time was the first obstacle. Luckily I'd purchased a pair of leather pants, and with a leather jacket and a face shield on my helmet, cruising sixty was like summer — almost.

It was a day's ride to Los Angeles, all on freeways. The biggest hazard was to keep from falling asleep since there is very little to focus your attention on.

While in Los Angeles for the weekend, brother John, who lives in the Los Angeles area, and I went to the TT motorcycle races at Ascot Stadium. A couple of Northern Californian favorites did very well and the entire racing program was a fascinating display of skill and sportsmanship.

Leaving Los Angeles on Monday morning we rode to Mexicali and by ten o'clock found ourselves on the El Comino del Diablo, or "Road of the Devil." On either side the desert is dry and without vegetation.

Crossing the Colorado River just before San Luis, a time zone is passed, an hour lost in the change from Pacific to Mountain time. About twenty miles east of San Luis we pulled off of the highway and rode out into the desert a mile or so and there made camp under the stars.

Never having owned an air mattress that would hold air all night I had decided that one was not necessary and would only be excess baggage. With thirty five pounds of luggage it is possible to live very comfortably. When making camp, first I lay down a ten by ten foot sheet of plastic Visqueen. On windy nights I lay with half of the plastic over me and half under, being careful to pick a direction where the wind did not blow into the top of my sleeping bag. Visqueen is very tough and keeps the weeds and cactus from sticking to my sleeping bag. Before I left home I had used a steam iron at very low temperature to iron creases in the Visqueen so that it folds compactly. I stopped at a bank in Guadalajara to cash a traveler's check and there can only be one way of describing the banking system of Mexico - mass confusion. The procedure required to cash a ten dollar traveler's check into one hundred and twenty-five pesos took a half an hour. This was during a lull in business and I shudder to think how long it would have taken had the bank been crowded.

The roar of a motor awakened me just after dawn. Here, to our surprise, with a hundred and twenty-seven miles of nothing we had camped in a gravel pit. While we broke camp two Mexicans in a gravel truck, the one which had awakened me, drove by three or four times shouting "Buenos Dias."

At the end of the El Camino del Diablo there is a little town called Sonoyta. Here it was necessary to register the bikes, and get a Turista sticker. The road turns south here for an eighty-six mile stretch into Caborca.

Four days were spent in Caborca just getting adjusted to Mexican living. It is necessary to stop thinking in dollars and start thinking in pesos. For one dollar you get twelve and a half pesos. Thus a peso is worth eight cents, and with careful shopping, will buy just as much as a dollar will in the U.S.

There are two grades of gas available in Mexico, eighty and ninety octane. After a few days of touring Caborca there were one hundred and thirty-three miles on the Honda since Sonoyta. I had the machine filled with 7 litros of ninety octane and the cost was seven pesos or fity-six cents. When you can travel one hundred and thirty-three miles for fifty-six cents, that's cheap.

When Saturday morning rolled around I had been away from home for a week, yet I had only made a thousand miles. So out of Caborca we rode and it was a good feeling to be traveling again. It was so much pleasure just to ride that we forgot to stop for lunch until late in the afternoon, after passing Hermosillo. Lunch was eight pesos and consisted of beefsteak, salad, potatoes and coffee, all of which was very good.

Next I became so interested in riding that I forgot to get gas and ran out near a little town called Los Pocitos. Two Mexicans with a dump truck came to my aid and gave me three litros. It was impossible to ride over sixty miles an hour because the gas was eighty octane.

Arriving in Guaymas just before dark we found that motel rooms were renting for forty pesos a day. Forty pesos is a lot of money in Mexico, so finding a campsite was in order. A few miles north of town we set up camp in the desert. The weather was warm and it was a very restful night's sleep.

With a motorcycle it is much easier to find a good camping spot than it is with a car. It is easy to ride way out into the desert and it is very difficult to become stuck, even with a machine like the Honda which has narrow tires.

Another day's travel brought us to Culiacan. Culiacan was so warm that I felt like the most ridiculous person on earth in my leather pants. It was amazing that the weather could have changed so much in one day's ride that covered only three hundred and seventy-five miles.

The pavement from Culiacan to Mazatlan left a great deal to be desired, although the scenery is beautiful and in the lowlands quite tropical. The base under the roadway must be very poor because the big trucks have beaten the roadway into a series of jumps. It was necessary to hold the speed down to fifty-five miles per hour and even then, sometimes the Honda's rear shocks would bottom while they were set in the soft position.

Just a few miles from Mazatlan is the Tropic of Cancer. Here the sun in its northernmost zenith is directly overhead.

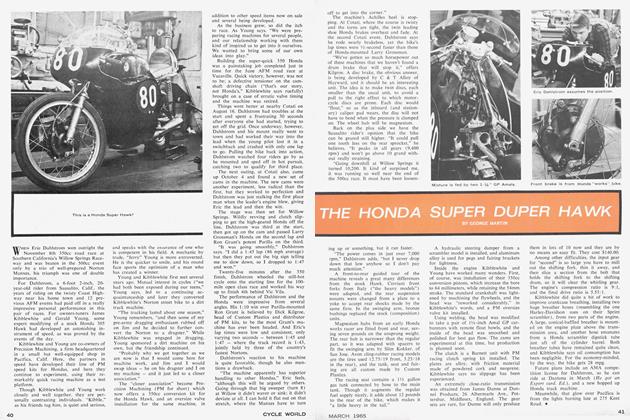

Before leaving Mazatlan I gave the Honda what I call the "one thousand mile service." This consisted of setting the tappets, watering the battery, adjusting the overhead cam chain, the rear chain and checking the air in the tires. The rear chain gets lubricated every two or three hundred miles also. In addition, since the weather was hot, the elevation low, and the gasoline poor I raised both of the main carburetor needles by one notch. Doing this in effect makes the gas-air mixture richer and keeps engine preignition down, especially at low rpms.

From Mazatlan to Tepic it was a short day's ride through landscape that varies from jungle foliage to cactus. Along this stretch of road there are many canyons and much gear shifting is necessary for the many grades and turns.

In some places the countryside is mountainous and dry. The small mountain ranges are interspersed with valleys, and in these valleys grow row after row of mescal cactus from which is derived Mexico's famous liquor, tequila.

Between Tepic and Guadalajara another time zone is passed and another hour lost. Guadalajara is a vast city, second only to Mexico City in population. Everywhere there are motorcycles, most of them loaded with goods of one kind or another, and most motorcycles serve a utilitarian purpose there. In the U.S.A. we ride as a sport and wave at other riders. Here this is not the case as motorcycles seem to be, for the most part, a way of getting from point A to B. Most of the machines on the highways throughout Mexico are Moto Islo's. The Islo is a machine made in Mexico mostly of Italian parts. Performance is somewhat low; however, reliability appears good.

(Continued on page 88)

Mexico's Highway 15 turns south out of Guadalajara and soon Lake Chapala comes into view. The highway winds its way along the shores of this huge lake for over fifty miles. After leaving the lake the road makes its way through mile after mile of mostly level country, which is heavily populated by Indians. They are industrious people and even the children carry very heavy loads upon their backs or supported by their heads.

After leaving Carapan the roadway be gins to climb into high mountain country, where.thin tall pines grow hundreds to the acre.

As dusk arrived in Zacapu, the speed ometer showed three hundred and twenty miles since Tepic. It was the time of day when visibility was the poorest so we stopped and reflected on the Mexican method of repaving a highway. The man ner of making asphalt here is to dump loads of sand alongside the road for a mile or so. This sand is then moved with a grader out into the middle of the road. Then along comes a ton-and-a-half tanker truck pouring oil into the sand. Next the grader drivers back and forth mixing the whole thing into one big mess. Sometimes this mess is rolled with a steam roller and sometimes by traffic. Needless to say the operation is quite delaying as it is necessary to drive through it.

It was well into evening when we ar rived in Morelia and it had taken twelve hours to cover three hundred and seventy miles. I found it difficult to believe the distance from Sonora to here. On the map it looks like nothing but in reality it is days of serious riding. .

In Morelia there is a magnificent hotel called the Hotel Roma. The place was built in 1844 and has a grand lobby one hundred and fifty by one hundred feet, with fifty-foot skylight ceiling. The rooms are huge with twenty-foot ceilings and eight foot tall doorways. All of this for only fifteen pesos a day.

Morelia's atmosphere is acquired by its ancient beginning in 1541. At the eastern entrance of Morelia there is an aqueduct with thirty foot archways. This aqueduct was built about 1789 and stretches for a mile down main street ending in the big fountain of a plaza.

Fifty miles from Morelia is the famous Mi! Cumbres or View of a Thousand Peaks. When looking back at these thou sand peaks you realize why the road has been so crooked since these are the moun tains through which you have just passed. For motorcycles the fifty miles to Mi! Cumbres is the best part of Mexico's high way 15.

All of Mexico's highways are marked with a kilometer post every few kilometers. in a radius from Mexico City. At each kilometer post a feeling of accomplish ment is achieved, as the distance of the trip diminishes.

Arriving in Mexico City late in the day we had ridden a total of over 2800 kilometers since Mexicali, far up on the border near California. Mexico City is the oldest city in America, having been founded in 1325. It has nearly five million people at an elevation of 7,349 feet.

The thing that gets to me the most about Mexico City is its traffic. About half of the automobiles are taxi cabs and their drivers get paid for the distance traveled. Therefore the cab drivers go full speed and other traffic is forced to keep up with them. Rather than have the Honda squashed between two buses or some equally disastrous fate, I parked the machine at a hotel and took taxis to noints of interest.

Leaving the outskirts of Mexico City, while buzzing along the expressway at sixty miles per hour, it happened. The first time in eighty-nine thousand miles on bikes, I've used my brain bucket for protection. With my head clear down between the mirrors I rode right up the exhaust pipe of one king sized vulture. I got "exhaust" all over the brain bucket and on the face shield clear down to chin level. The encounter caused the vulture to lose many feathers; however, it was still able to continue flying.

Two hundred and thirty-three kilometers from Mexico City is Zopilote Canyon, or Vulture Canyon. Here stone columns rise in walls above walls; on each plateau cactus clings precariously, growing straight up toward the sky.

Just as tfle speedometer snowea tnree thousand miles since my home town of Sonora, we topped the last hill and beheld AcaDulco.

Grand hotels lit in a blaze of light form a circle around the bay. Acapulco is called Mexico's Riviera and after checking into a nice fifteen peso a day hotel I began to live the life of a rich tourist.

The very by lying on in front of pleasure of surf has to first day I got a fine sunburn, the beach for just a half hour, the Hotel Playa Hornos. The floating around in the warm be felt to be fully appreciated.

There was also a carnival in progress. People walk around the Zocala and break eggshells filled with confetti over each other's heads. The big trick is to throw confetti into people's faces when they have their mouths open laughing.

The weather in February is just about perfect for motorcycles. It is possible to ride any time of day or night in a T-shirt. There were thousands of tourists in Aca pulco but none who rode motorcycles from the states. Most of the machines that the Mexicans ride in the vicinity of Aca pulco are Yamahas, which they have been importing for years. There were several 1958 Yamahas and they seemed to run well. I rode the Honda to an oil store, and there, drained the old oil. While putting in two fresh quarts of thirty weight, a crowd of people gathered to look at the machine. The proprietor of the store took the old oil and it filled two quart cans. The crowd was amazed and I was surprised also, be cause the Honda had used no oil since California.

The cost of living is very low in Aca pulco and it is possible to eat good Mexican food, in a clean restaurant, for fifteen pesos a day. The big meal of the day is lunch, consisting of five courses for five pesos.

The local people are quite friendly and eager to point out the fine points of their town. Nearly all women wear skirts and little or no makeup. This is very appealing after all the pants and various colored hairdos of the north. Many women are also seen carrying heavy loads, such as three or four gallon crocks of milk, upon their heads, and they balance them without using their hands.

After ten days in Acapulco I took a side trip of one hundred and fifty miles up the coast to a little town called Zihuatanejo. Fifteen mintues after arriving there I decided to move from Acapulco.

So began a new phase of vacationing. Zihuatanejo is what Acapulco must have been twenty years ago, before the neon lights. It has a beautiful bay with seven good beaches, warm water, and good hot sun.

The last forty kilometers is bad road. For this reason there are very few tourists, and most of those who are there, flew in. There are just enough tourists to have interesting conversations once in awhile, but not so many that they have taken over the place. The town has no electricity except in some business houses and some hotels. My hotel had kerosene lamps, very nice owners, and a price tag of forty-two pesos a week.

After being there for a few days I paid seventy pesos to rent a horse for a week. This horse and I rode all around the town and to several beaches inaccessible by car. It was like the wild west when I rode "Horse" up to the busiest restaurant on Main Street. There I got food for myself and a bucket of water for "Horse." Maybe a horse can go where a motorcycle cannot; I don't know, but they are very close and certainly a machine is much faster.

Several days of my stay I rode the Honda to a beach several kilometers from town. It was no problem to ride along, near the water where the sand is hard, at twenty to twenty-five miles per hour.

The people in that area must be some of the friendliest in the world; however, by our standards, they are very poor. Zihuatanejo has a population of around two thousand, but only about twenty-five automobiles, and three motorcycles.

After a month in Acapulco and Zihautanejo, it was time to pack the duffle bag for the ride home, by way of Texas. Within two days we were back in Mexico City and the noises of a big town.

Many strange financial things happen in Mexico. This is because the Mexicans have a completely different viewpoint from ours about how, and what, to charge. For instance, the hotel room in Mexico City was twelve pesos the first night, but fifteen pesos for the second. This was because the manager figured he could get fifteen without making us mad enough to make it worth moving. He was right.

Within a hundred miles the rolling hills gave way to steep mountains with deep canyons. Everyone who rides a bike should cover the next one hundred and twentyseven miles of Highway 85 sometime in his life. Between the two towns with the Indian names of Ixmiquilpan and Tamazunchale, the turns are tight, well paved, and a pure joy. The last sixty miles into Tamazunchale would have only been about thirty-five miles, as the crow flies.

With twelve hours of riding, in which no one passed us, we quit late in the evening at Ciudad Victoria, with four hundred and sixty miles for the day. This was no record, but a satisfying day's ride, considering the many turns.

From Victoria to Brownsville, Texas, a distance of one hundred and ninety-six miles, it was open country, and difficult to hold the speed down to sixty-five. The U.S. Custom's check at Brownsville was very thorough, even to the point of looking through the Honda's tool kit.

From Victoria, through Brownsville to Corpus Christi it had been a day's ride of three hundred and seventy-five miles. Another leisurely two days' travel for four hundred miles brought us to, of all places. Sonora, Texas. Sonora, Texas was much different from my home town of Sonora, California.

A few miles from Sonora, Texas, the Honda's first mechanical failure of the trip happened. The throttle cable broke near the handgrip. I taped the frayed end of the cable to the twistgrip, and was thus able to operate the throttle in the ordinary manner, although somewhat inaccurately, until El Paso, a distance of nearly four hundred miles.

Dawn the following morning found us almost in Yuma, Arizona, and since there were several hundred bike riders in town on a tour, we stayed and bench raced with them for about four hours. The head winds were strong and the sand was blowing from Yuma to Palm Springs and leaving Palm Springs it began to rain. Los Angeles boasts a record of having no rain for over three hundred days. This was not one of them, and not having rainsuits, we were dripping wet when we reached my brother John's house. It had taken slightly over twenty-four hours to cover the distance of 864 miles.

Total mileage for the trip was seven thousand, three hundred and seventy miles, with a gasoline cost for me of forty-six dollars. It was a nearly perfect twomonth vacation on my half price ticket and my head is full of memories and pictures that I can review for a lifetime. •