THE SERVICE DEPARTMENT

GORDON H. JENNINGS

SPEED-TUNING PROBLEMS

I have a 250cc Zundapp I use for scrambles and enduros. I have been hopping it up, and on the subject of timing I got most of my help from your report on two-cycles. Now I need your help again.

My problem is with ignition timing and the exhaust system. 1 don't know what timing to use. Some people say that for more power, make it fire close to top dead center, others say make it fire farther from tdc. I read in your report that when raising the compression ratio, which I have done, ignition timing should be advanced. This would mean firing farther from tdc, is that correct?

My exhaust isn't correct either. I made an exhaust system as you suggested in your report; but I get better performance with the stock exhaust pipe without the muffler. Could this be due to the 8-inc/i rani tube that I have added between the barrel and the carburetor? John A. Sanders, Jr. Pensacola, Florida

I sincerely hope that I did not say that increases in compression would require an increase in ignition advance, for the oppo site is usually true. The reason for having the ignition spark occur before the piston reaches top dead center is that the fuel/air mixture does not ignite and burn com pletely the instant a spark is supplied. There is a lag, while the flame spreads throughout the mixture and burning oc curs. For maximum power, virtually all combustion must be complete before the piston reaches tdc and starts downward on the expansion, or power, stroke and to achieve that end, combustion must be ini tiated in advance of tdc.

Unlortunately, there are no hard and fast rules regarding ignition advance. The whole thing depends entirely on how much time is required for complete combustion and that is rather a complicated matter. Broadly speaking, the time required for complete burning will depend on combus~ tion chamber shape and size, compression ratio, and mixture turbulence. Obviously, it will take longer for the flame to spread through a large combustion chamber, and also the compacting of the mixture that occurs with high compression ratios will shorten combustion time. Further, com bustion time will also be shortened when the porting of an engine imparts a lot of turbulence to the incoming mixture, which will still be swirling around mightily in the combustion chamber at the moment of ignition and will, therefore, burn more quickly.

All of these factors establish the time required for complete combustion; that brings us to another important factor: the time available. In an engine turning 3000 rpm, 10-degrees of crank-angle is a much longer time, in terms of fractions of a second, than when the engine is turning 6000 rpm - in fact, the doubling of crankshaft speed cuts the time in half. Thus, an ignition advance sufficient for complete combustion at 3000 rpm would not be adequate at twice that speed. If the combustion time held constant, our 10degrees of advance at 3000 rpm would have to be 20-degrees at 6000 rpm.

Complications again enter the discus sion at this point, because in virtually all engines, combustion time is not a con stant. Such things as mixture turbulence, increasing with engine speed, accelerate the combustion process enough so that, within reasonable limits, increases in en gine speed will be matched by a more rapid rate of combustion. This allows us to use a fixed advance, with the same setting for all engine speeds. In practice, however, there will not be enough mixture turbulence created under, say, 3000 rpm, to have much effect on combustion. Con sequently, we must either sacrifice per formance below that speed or adjust the low-speed advance to the requirements -a job that is usually done by a centrifugal automatic advance mechanism inside the ignition breaker system. These automatic advance mechanisms usually wind over to full advance by the time an engine is up into its power range, but they have a very good effect on torque and low-speed smoothness. Racing engines, which are never asked to work outside a fairly narrow power range, can do very nicely with a fixed ignition advance.

(Continued on Page 12)

I realize that all this information is of little direct benefit to you. But, unfortunately, unless you have access to a dynamometer, there is no easy solution to your problem. The best I can suggest is that you rig a manual spark control, and then run along at full speed (preferably up a slight hill, which will load the engine enough to hold it down to a speed midway between the power and torque peaks) and play with the spark until you get the most power.

SPARK PLUG LIFE

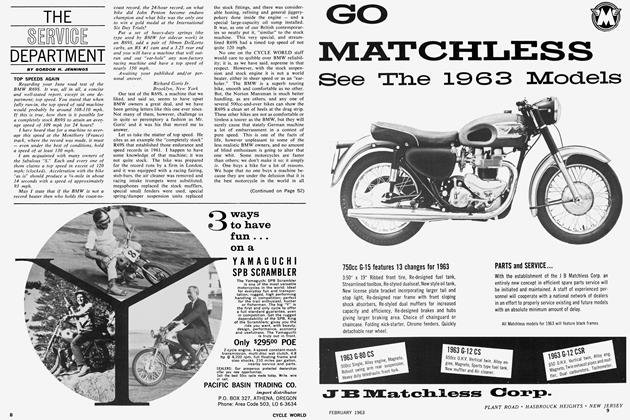

I have a 50cc Yamaguchi Scrambler which 1 use for about half scrambling and half road racing. 1 have a lot of trouble with the spark plugs. After putting in a new plug the engine will crank up on the first kick for about four times. Then, for about ten to fifteen more times it will start, but only after a lot of kicking. A plug will usually last only about two weeks.

1 have read much material on plugs for two-strokes, but no improvement will avail. Clay Bell Daleville, Alabama

A spark plug manufacturer’s representative once told me that his employers would be most happy to see all motor vehicles powered with two-stroke engines, as their products would sell much more briskly. This was, of course, an oblique way of saying that two-stroke engines are particularly hard on spark plugs, and that frequent replacement will be necessary. And, unfortunately, this estimate of the situation was entirely correct.

A two-stroke engine punishes its spark plugs in two different ways: first, because there is a power stroke with every revolution of the crank, it has to fire twice as often as a plug in a four-stroke engine and is working under a doubled thermal loading; second, it is subjected to a constant bathing in an oil mist, which vastly increases the rate at which fouling deposits build up. This creates conflicting requirements in the plug’s heat range characteristics. To resist the high thermal loading, the plug should be “cold,” offering a short internal heat-path for good tip cooling. And, on the other hand, it should be “hot” so that deposits will be burned away and fouling will not occur.

In most instances, motorcycle manufacturers specify a plug that is hot enough to be free of fouling, as that is a more immediate problem than a short plug life in service. But, when the motorcycle in question is ridden very hard, the specified plug will be too hot, and cooks its life away quite quickly. When this is the case, a change to a colder plug will be of some help, but of course the colder plug will not be as resistant to fouling and care must be taken that the engine is not allowed to idle too long. In extreme instances, it may be necessary to use a hot plug for starting and warm-up, and then switch to a colder plug for high-speed work.

(Continued on Page 49)

Also, in two-stroke engines, the operator may be responsible for some of his problems with spark-plugs. We have noticed that many people are very offhanded in the way they mix oil and fuel. They seem to feel that if a little oil in the fuel is good, a lot of oil will be terrific — and a surplus of oil will increase the fouling problem. Ideally, mixing should be done by pouring fuel and oil into a can, in the proportions recommended by the engine’s makers, and then shaking well to blend the mixture before filling the motorcycle’s tank.

At present, there are ignition systems being developed that will to a great extent overcome the fouling problem and permit the use of colder plugs — which will last longer. But, until these come into wider use, we will have to accept short plug life to get the overall simplicity and reliability offered by the two-stroke engine.

SPEEDOMETER ERROR

For months, l have been puzzling over the speedometer results in your road tests. You print, “30 mph, actual . . . 27.2”. Does this mean that when the speedo reads 30 mph, your actual speed is '27.2 mph? Or is it that your actual speed is 30 mph when the speedo reads 27.2 mph? John P. Covington New York, N.Y.

You had it right in the first instance: when the speedo read 30 mph, the actual speed was 27.2 mph. We list the indicated speeds, 30, 50, 70, and then the true speeds. Incidentally, we check for error in 10-mph increments from 30 mph through 80 mph, and make several test runs at each speed to reduce the possibility of error on our part. And, coincidentally, I might mention that most speedometers err considerably; many of them “award” the rider with a full 5 mph at an indicated 70 mph. •

“How were the trials?”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

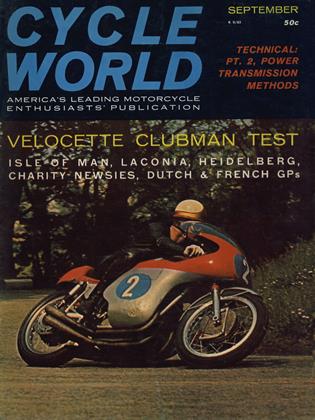

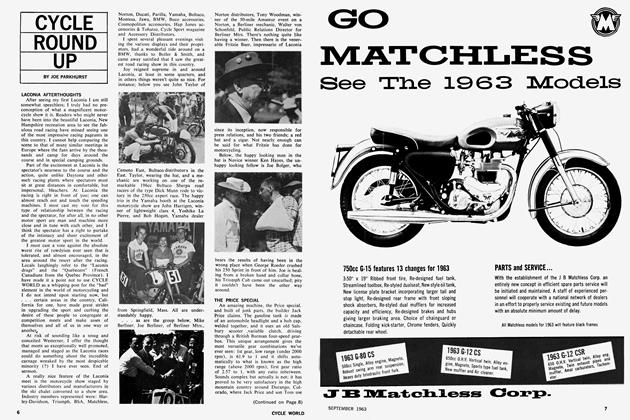

Cycle Round Up

September 1963 By Joe Parkhurst -

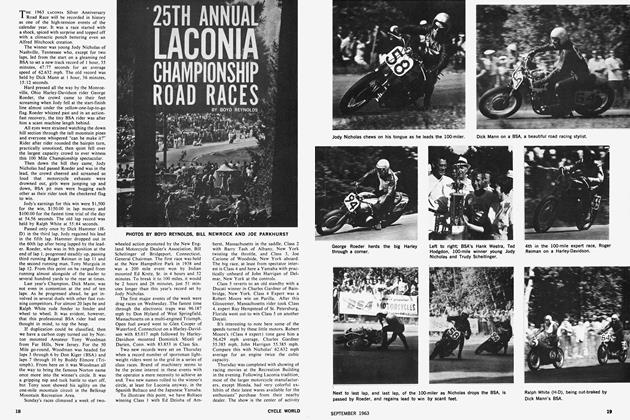

25th Annual Laconia Championship Road Races

September 1963 By Boyd Reynolds -

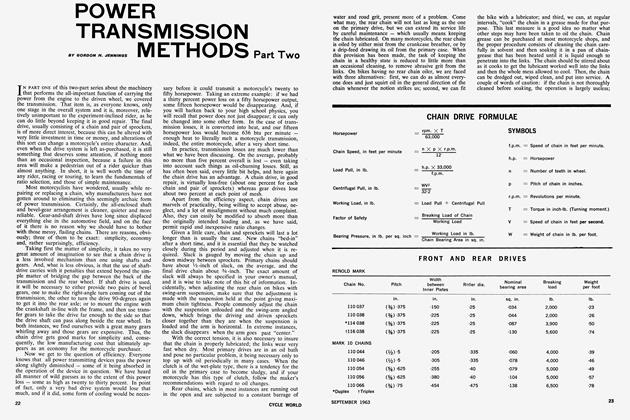

Technical

TechnicalPower Transmission Methods Part Two

September 1963 By Gordon H. Jennings -

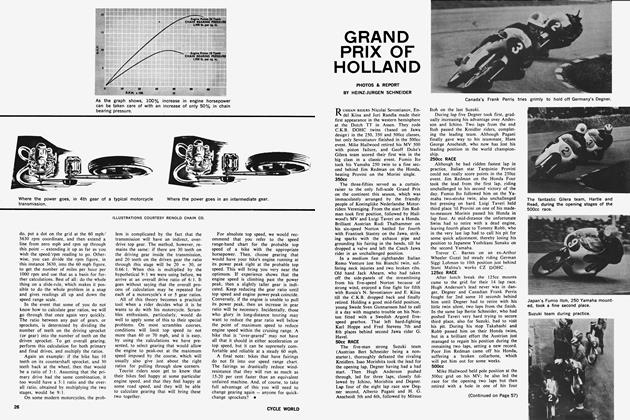

Grand Prix of Holland

September 1963 By Heinz-Jurgen Schneider -

The Most Dangerous Moment

September 1963 By J. R. Beall -

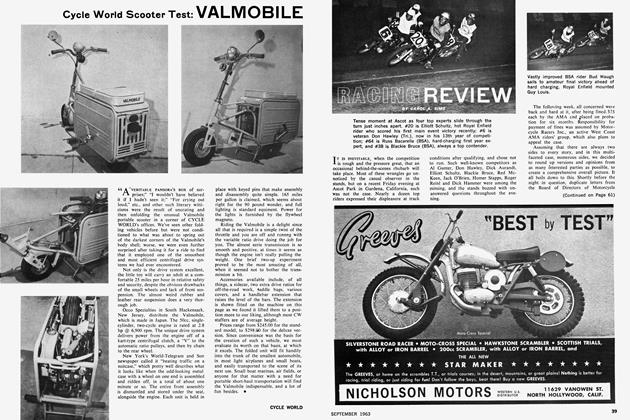

Cycle World Scooter Test:

Cycle World Scooter Test:Valmobile

September 1963