THE SERVICE DEPARTMENT

GORDON H. JENNINGS

IGNITION SYSTEMS

Here is my subscription, and with it I am sending a few questions.

How soon do you think that the “spark pump” ignition will be used on British motorcycles and scooters? Any news?

Why are not flywheel magnetos used on larger displacement motorcycles, such as the 500cc — 650cc singles and twins? It seems, from my experience, that flywheel magnetos for ignition (and lights) would be more reliable. The operating speed would not really matter. Witness the high rpm of the Mercury racing outboard motors.

CHARLES W. HELVIE Kokomo, Ind.

For those of you who may not have heard of it, the spark pump of which Mr. Helvie speaks (properly called the “Clevite spark pump”) is a device currently being used as an ignition source for small, single-cylinder industrial engines. The spark pump is precisely what it sounds like — give it a squeeze and it pumps out a spark, which is of sufficient intensity to fire the fuel/air mixture in a gasoline engine.

The source of power is a stack of small, thin, synthetically-grown crystals. When pressure is applied to these crystals, each one produces a small amount of electricity. The crystals are arranged with a definite polarity, like cells in a battery, and the voltage accumulates in intensity through the stack.

Actuation for the device is provided by a compound system of levers, with the pressure pulses coming from some sort of a cam. In fact, a cam not unlike the one used with an ordinary contact-breaker system would do the job very nicely.

The spark pump does have limitations. The crystals must be given time in which to recover between pulses but the interval is so short that its effects can be ignored when we are considering single cylinder applications. Of course, this is not necessarily true of high-speed multis. Where recovery-interval problems were encountered. it would always be possible to provide a spark pump for each cylinder. And. too, that would eliminate any need for a distributor — a necessity with a single spark pump serving two or more cylinders.

We understand that the total number of pulses available from any single unit runs well up into the millions before there is a perceptible deterioration in output voltage. That means thousands upon thousands of road miles would be covered on the average motorcycle before replacement would be required.

In our opinion, the use of the spark pump will spread to all kinds of engines. Although it is surely more expensive — at least for the present — than the time-honored. battery-and-coil ignition source, its advantages would seem to indicate that many manufacturers will find it well worth the extra money.

Just to set the record straight, they do know about the Clevite spark pump in England and have shown a strong interest in its possibilities. According to rumor, there is at least one British manufacturer negotiating for the rights to produce the device under license.

As for the flywheel magneto, it has too many shortcomings - when scaled-up or extended in application — to become popular generally in the form you have in mind. On chain saws and other such industrial and/or scooter engines it is just fine, but that is about as far as it goes. And, unless memory fails us, that Mercury outboard engine you mention does not use a flywheel magneto at all. Like most of the big. powerful outboard powerplants, they have a conventional magneto, driven from the crankshaft by^a toothed timing belt.

There are good reasons why the flywheel magneto has such restricted applications. In the first place, it is not easy to make the thing function as a source of power for both ignition and lighting. The requirements are too different. Not only that, but not since the old horizontalsingle Moto Guzzi have we seen a motorcycle engine of any size with an external flywheel — and it wouldn’t be too wise to bury all that wiring inside the crankcase.

Another factor is the need for having some form of automatic ignition-advance control. Engines do not have the same advance requirements at all speeds. Any engine with a fixed ignition point will, therefore, suffer an unnecessary power deficiency through a large part oY the running speed range. In a conventional magneto, or distributor, this automatic advance may be provided by the simple expedient of having centrifugal flyweights (like those in any automobile distributor) incorporated in the drive. In a flywheel magneto, this sort of progressive-advance mechanism is not so easy to provide.

On the other hand, many of the alternating-current generating systems being used today are a great deal like the flywheel magneto. Except that, usually, the current goes through a rectifier and to a battery before (or jointly with) supplying the ignition coil. Many, indeed most, of these “alternators” are certainly not wholely unlike the flywheel magneto of which you seem so fond — although they are often, in effect, turned “wrong-sideout.”

You will be further heartened to hear that the Wipac-Pacy Company, in England, has developed a form of flywheel magneto specifically for two-strokes that reaíly justifies your enthusiasm for the type. Unlike other systems, Wipac-Pacy’s gives a spark when the points close, rather than open. This, we are told, gives a much more rapid voltage build-up than the conventional arrangement. The advantage derived from this is that the voltage reaches such an intensity, so fast, that there is no time for it to drain off across, for example, a wet spark-plug insulator. It is literally forced to arc past the plug’s .025.030 in. electrode/ground gap.

The rapid voltage buildup is also responsible for an extreme resistance to oilfouling of the plug. The spark plug can be completely doused in oil and still fire strongly enough for instant starting and miss-free running.

Yet another relatively new type of ignition .system is the kind that uses electronics. Several companies, both here and abroad, have been experimenting in this field and the results have been most encouraging. The only system of this type that has been used on a motorcycle is one built by Lucas.

Lucas’ device is made for four-cylinder, two-stroke or eight-cylinder, four-stroke engines and will deliver a furious 1000 sparks per second, if that ever becomes necessary. Instead of a conventional breaker-point set, it uses a small disc (driven at either half or full engine speed) that has four magnetic poles. A magnetic pickup head carries small pulses from this disc to a trigger-amplifier, which is supplied with high-tension voltage from a spark generator. The trigger-amplifier “valves” high-tension pulses to a fairly conventional distributor, which directs the spark to the appropriate cylinder.

This system owes its efficiency to the fact that there is no contact breaker set. Everything in it is either entirely electronic or has only rotary motion and there is, consequently, no possibility of point-float or $nv of the things that cause the efficiency of the conventional type to drop with high revolutions.

The Lucas system, the others like it, and to some extent the spark-pump are for the future, however. At present the battery/ coil, remote magneto and flywheel magneto systems are doing their respective jobs nicely, and there are good reasons for the continued use of each.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

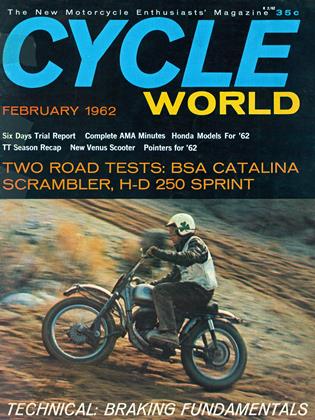

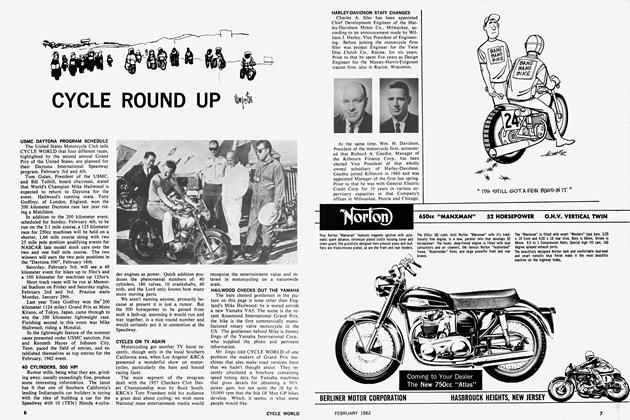

Cycle Round Up

February 1962 -

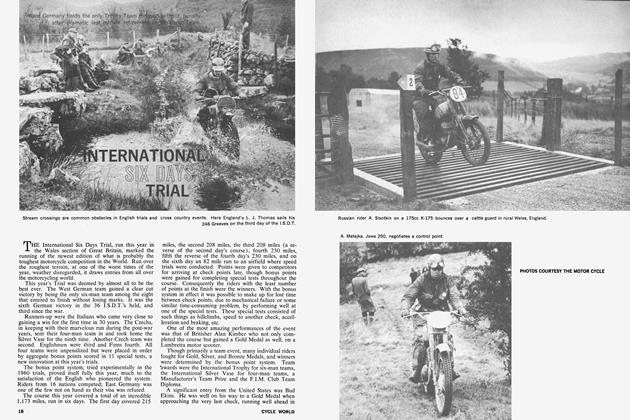

International Six Days Trial

February 1962 -

Technical

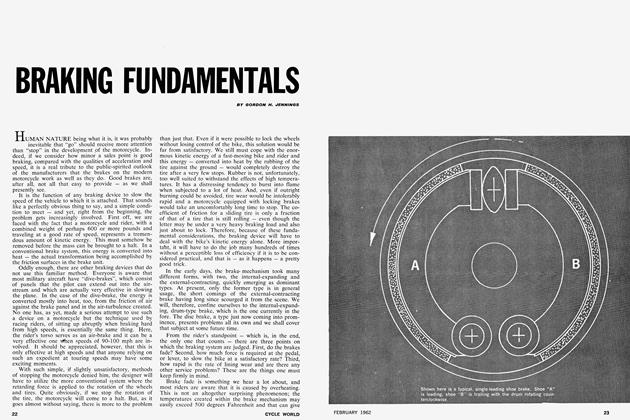

TechnicalBraking Fundamentals

February 1962 By Gordon H. Jennings -

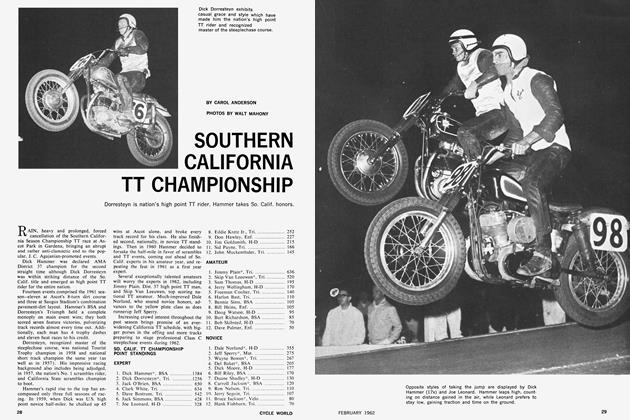

Southern California Tt Championship

February 1962 By Carol Anderson -

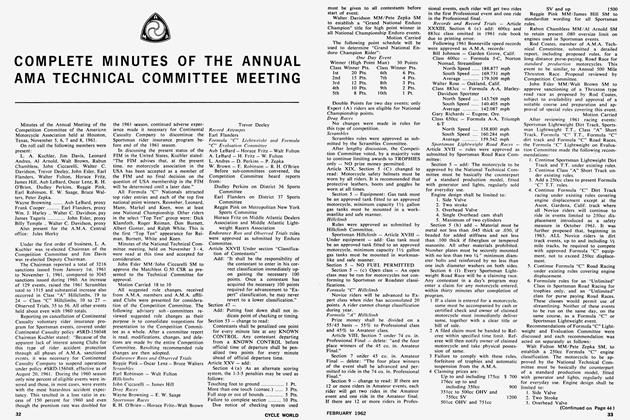

Complete Minutes of the Annual Ama Technical Committee Meeting

February 1962 -

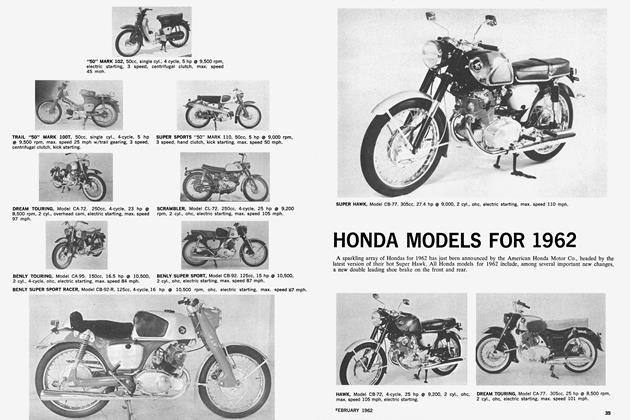

Honda Models For 1962

February 1962