ORIGINAL HONDA ELSINORE

How the epic ’70s Honda 125 and 250cc Elsinore launched the motocross craze

October 1 2022 DAVID DEWHURSTHow the epic ’70s Honda 125 and 250cc Elsinore launched the motocross craze

October 1 2022 DAVID DEWHURSTORIGINAL HONDA ELSINORE

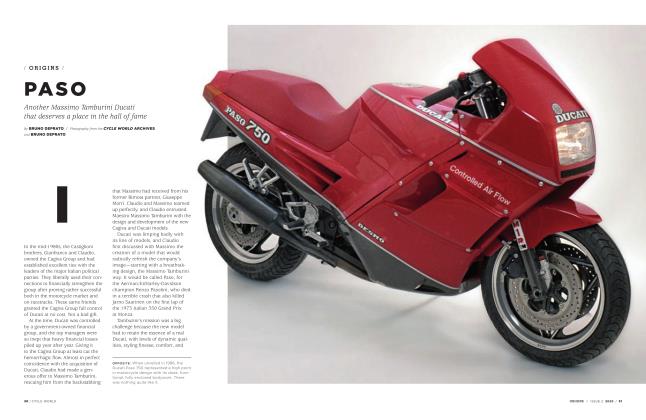

ORIGINS

How the epic ’70s Honda 125 and 250cc Elsinore launched the motocross craze

DAVID DEWHURST

Motocross icons are not hard to spot along the motocross timeline. Bill Nilsson’s Albin-powered Husqvarna four-stroke, Jeff Smith’s factory BSA, Torsten Hallman’s Husky two-stroke, Paul Friedrich’s CZ: Each of these moto masterpieces was a high-water mark in the gradual rising tide of racing development.

Honda’s 1973 Elsinore CR250M was likewise a high-water mark for the genre, but one unlike anything before it. The Elsinore would quickly prove to be motocrossing’s tsunami. Within weeks of its March introduction, Honda’s first-ever racing twostroke had flooded the start gates of tracks across America. Motocross had changed forever.

Honda’s new rocket wasn’t much faster than the most tricked-out Bultacos and Maicos of the day. Its advantage was that right out of the crate, a stock Elsinore was a match for its highly modified competition. Just as significantly, it was reliable, reasonably priced, and a Honda.

Factory rider Gary Jones remembers riding early prototypes and marveling at their speed and reliability. “The big thing was everything just worked,” Jones says. “The clutch, the transmission, and even the nylon-lined cables were just so good. Of course, the brakes were one thousand percent better than anything else out there.” Asked how good the production Elsinore was, Jones chuckles, “Well, when we started having things break on the factory Honda, I went back to a modified production bike and won the title on that.”

What’s truly amazing about that first Elsinore, code name 335A, is that virtually nobody at Honda knew it was being developed. It was a skunk works project run by engineers with virtually no motocross experience. Chassis engineer Sasaki Osca remembers being moved from CB Honda streetbikes to help: “Everything was developed in Japan, but with much reference to Europe.”

Honda boss Soichiro Honda was completely against two-stroke race engines, but realized that light weight was essential. Sasaki Osca remembers Mr. Honda coming in one day after finding out about the development of prototype 335C and telling the development team, “If it has to be a two-stroke, it must win.” Mr. Honda was so obsessed with the bike’s success that he personally attended a number of test sessions in California. American test rider Jim Wilson remembers shaking Mr. Honda’s hand at Indian Dunes before an early test of production prototypes where movie star Steve McQueen was also along to give his impressions.

With such commitment from the highest level, it’s not surprising that the European manufacturers were left wondering what just happened when Honda pulled the racing rug from right underneath their leaden feet. But the 250 Elsinore would prove to be a minor shock in comparison to the 125cc Elsinore Honda launched late in 1973.

Compared to the Bultacos, Husqvarnas, and various Sachs-powered competitors, the 125cc Elsinore rolled out of the crate with a huge advantage. Not only was it faster than anything else, but like its bigger brother, the 125cc Elsinore was reliable and only cost $749, about $5,000 in 2022 dollars. It was a blow that would send the European manufacturers into a giant tailspin.

DG Performance marketing guru Ken Boyko remembers going to a night race at Irwindale Speedway late in 1973. “You could race five nights a week in LA back then, and Irwindale was the biggest,” Boyko says. “I’ll bet 90 percent of the bikes on the line that night were Elsinores.”

One huge irony of the Elsinores is that Honda envisioned its bikes to be good enough not to need any aftermarket parts to compete with the much-modified competition. In reality, the Elsinore single-handedly created a new tsunami of aftermarket companies. Almost overnight, every tuning shop with a welder and a port grinder jumped at the opportunity. Before long, there was a smorgasbord of go-fast parts that included expansion chambers, swingarms, shocks, cylinder heads, and more.

The list of tuning companies was long, but a few stood out. FMF was a huge influence with its exhaust pipes and ported cylinders, and a young kid called Marty Smith hung his name on the brand. A few miles south another youngster, Bob Hannah, was signed by DG Performance to promote its fast-growing business. Boyko remembers how the Elsinore single-handedly propelled the business. “There never was a more important bike,” Boyko says. “Nothing even came close. We were porting one hundred Honda cylinders a month and doing five or six hundred pipes a month. It was insane.”

“I’ll bet 90 percent of the bikes on the line that night were Elsinores. ”

Both Elsinores were an instant hit, and racers scoured dealerships across the country to find them. It wasn’t unusual to pay hundreds of dollars over the retail price and sometimes it meant driving halfway across the country to find one. It didn’t matter. Young riders saw an inexpensive and reliable way to become competitive in the exploding sport of motocross. A long drive in a pickup truck was a small price to pay.

Honda’s reign lasted a couple of years, thanks in part to all the aftermarket support. But the production bikes were little changed, and Suzuki and Yamaha introduced all-new bikes that easily challenged the Elsinore’s title. Chassis engineer Sasaki says that Honda had to divert a lot of its resources to developing emission-control systems for cars in the mid-’70s and motocross development paid the price. “I was moved from

motocross to the emissions side.”

Whatever the reason, factory development of the Elsinore slowed to a crawl. Materials were improved for reliability, and minor improvements were made to power and handling. But while Honda polished around the edges, Yamaha and Suzuki went in for the kill. YZs and RMs of the late ’70s quickly clawed away at Honda’s early lead, and no aftermarket swingarm or ported cylinder could reverse the tide.

By 1976 that original tsunami had crashed on the beach and rolled back. The competition was quickly flooding American dealerships with equally reliable alternatives that were proving to be even faster than anything Honda had to offer. If Honda had been a European brand, it might have sat there and let the water flood over it.

Instead, the company came back swinging in 1 978 with a whole new Red Rocket that would again set the sport on fire. The rest, as the saying goes, is history.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Feature

FeatureCYCLE WORLD 10 BEST BIKES 2022

Issue 3 2022 By Justin Dawes, Michael Gilbert, Bradley Adams2 more ... -

SECRET STASH

Issue 3 2022 By CHARLES FLEMING -

UP FRONT

UP FRONTTHE TEN REST

Issue 3 2022 By MARK HOYER -

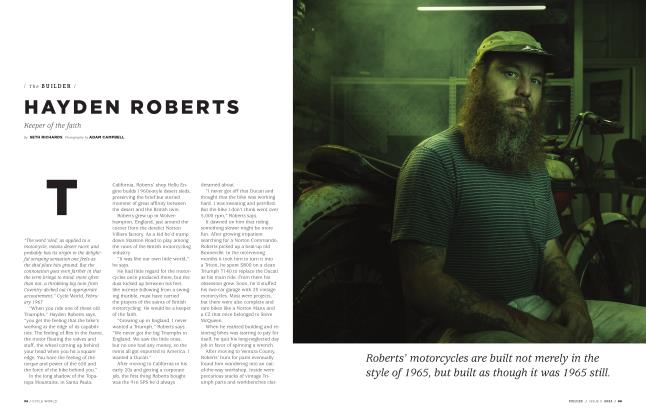

The BUILDER

The BUILDERHAYDEN ROBERTS

Issue 3 2022 By SETH RICHARDS -

TDC

TDCSIGNS OF CHANGE

Issue 3 2022 By KEVIN CAMERON -

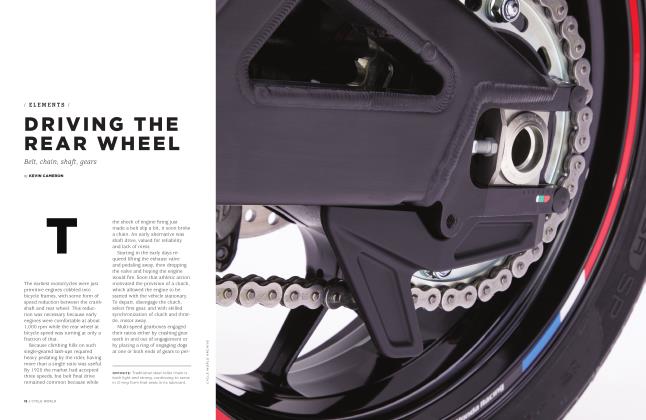

ELEMENTS

ELEMENTSDRIVING THE REAR WHEEL

Issue 3 2022 By KEVIN CAMERON