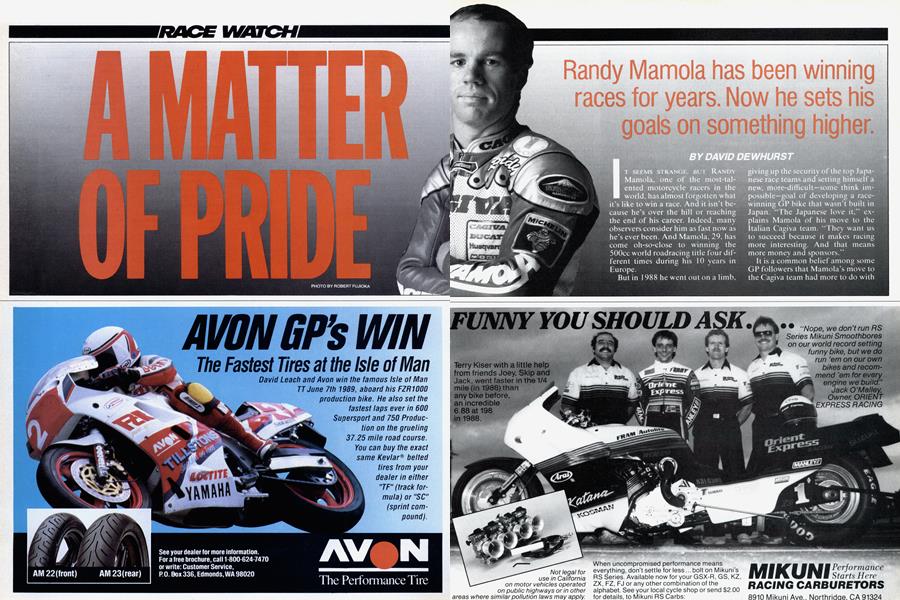

A MATTER OF PRIDE

RACE WATCH

Randy Mamola has been winning races for years. Now he sets his goals on something higher.

DAVID DEWHURST

IT SEEMS STRANGE, BUT RANDY Mamola, one of the most-talented motorcycle racers in the world, has almost forgotten what it’s like to win a race. And it isn't because he's over the hill or reaching the end of his career. Indeed, many observers consider him as fast now as he’s ever been. And Mamola, 29, has come oh-so-close to winning the 500cc world roadracing title four different times during his 10 years in Europe.

But in 1988 he went out on a limb. giving up the security of the top Japanese race teams and setting himself a new, more-difficult—some think impossible-goal of developing a racewinning GP bike that wasn’t built in Japan. “The Japanese love it,” explains Mamola of his move to the Italian Cagiva team. “They want us to succeed because it makes racing more interesting. And that means more money and sponsors.”

It is a common belief among some GP followers that Mamola’s move to the Cagiva team had more to do with increased sponsorship and money for the Mamola bank account than the general well being of the sport. But they obviously don’t know Mamola, a racer who already gives 20 percent of his prize money to charity. Annoyed by suggestions of greed, Mamola quickly sets the record straight. “I got offered a phenomenal amount of money by Honda last year,” he says. “They just asked me what it would take and I told them. It was way more money than Cagiva offered. They (Honda) came back with the money three weeks later. I said no,” he reveals.

Yamaha and Suzuki also were knocking at Mamola’s motor-home door. But Mamola wasn’t after the money and he returned to fulfill the second half of his two-year commitment to Cagiva. But he did use Honda’s high-buck offer as a lever. It was just what he needed to persuade Cagiva’s millionaire owners, the Castiglioni brothers, to institute sweeping changes to the fledgling team. “We had too many chiefs and not enough indians,” says Mamola, referring to incidents like an untightened countershaft nut that caused him to high-side during practice for last year’s USGP. All told, it was a disastrous 1988 season, one that convinced most observers that Mamola and the Italians stood little chance of success.

Mamola’s long-time friend and mechanic George Vukmanovich, who’s been with Mamola since his earliest races in Europe, knows how tough a year 1988 was. “I’ll give Randy credit. Kevin Schwantz or Eddie Lawson wouldn’t be hanging around here after the year we went through. Wayne Gardner wouldn’t be here, either. He’d have gone back to Australia.” says Vukmanovich.

“Yes, it is hard on me sometimes,” admits Mamola. “Inside, I'll start to wonder, Ts it me or is it the bike?’ But then I get out there with these guys and I brake just as deep as they do and sometimes a hell of a lot deeper. I just can’t get the bike turned, but I know I still have the talent.”

So why does Mamola continue to strive for what most people think is almost impossible? Put simply, it’s the ultimate challenge for one of motorcycle racing’s most-dedicated men, one who’s prepared to do practically anything, including give up almost-certain victory, to help the sport of racing. Winning obviously doesn’t mean everything to Mamola. “You know, when I finished third in Belgium last season (his highest finish on the Cagiva), it was the first time a non-Japanese bike had been on the rostrum in 12 years,” Mamola says with obvious pride. “That was such a great moment. I was so emotional. It was better than winning my first GP, better than getting second in the championship, better than anything.”

But things rarely have gone so well for Mamola. At this year’s GP in Italy, the sight of his last victory ( 1987, on a Honda), there was little chance of climbing the victory podium. After two days of qualifying. Mamola could only manage a distant 1 Oth position on the starting grid. Despite Cagiva investing over half a million dollars in four new frames since the USGP in April, the bike still wasn’t handling well. At Laguna, the team thought it had weight bias too low and too far forward, causing wheelspin. But in Italy, there was talk about scrapping a half-million-dollar mistake and going back to the original frame.

Obviously, Cagiva's problem isn’t a lack of money. In fact, one Japanese team manager speculates that the new Cagiva probably cost more to build than any of the Japanese bikes. What the Italian team lacks is grand prix savvy. “They haven’t designed race-winning engines for years.” explains Vukmanovich. “This team just doesn't have the experience that the Japanese do. We have to learn by our mistakes. The Japanese can look back and say, ‘We tried that in 1970 and it didn't work.’ We don’t have that experience.”

What Vukmanovich doesn’t say is that with their years together on the Suzuki and Honda factory teams, he and Mamola probably have more development experience between them than any two other people in the Italian paddock. “We have basic theories,” he says, “but that sometimes gets lost in the translation.” Mamola amplifies: “There’s this Italian pride thing,” he says, shaking his head in frustration, “and sometimes it’s hard to convince people that stuff needs changing.”

Vukmanovich agrees. “At a Japanese company, if you say it needs changing, it’s thrown away and changed. Here, you have to convince them it needs changing. That’s the hardest thing,” he says.

Imagine Mamola’s task at the end of last season, when after making obvious progress, he demanded, essentially, a new bike. “The improvements we needed were big ones.” says Vukmanovich. “We needed to lose about 25 pounds. We’ve done that, but when you talk about that big of a change, you’re not talking about the same bike anymore.” So, with a new and lighter motor in a new and lighter frame, the development started over again for 1989.

“We’ve not gone a long way forward,” admits Mamola. “We’ve gone in a lot of different ways, but we have taken a few steps forward. That pleases me.”

But just how far off is their first victory? Vukmanovich laughs, “Well, next couple of decades? Seriously, I think we’re really close.” Mamola concurs, “Yes, I can see it happening. We can win, and that will be great for the sport when it happens.” In the meantime, the likable Californian is going to continue doing the things he enjoys most: riding and thrilling the crowd.

“I’m an entertainer,” says Mamola. “Schwantz and Lawson, we’re all entertainers, but I pick up on stuff quicker than they do. It doesn’t take but one second on a warm-up lap to wave at someone, and then everyone thinks I’m waving at them.” Other crowd-pleasing ingredients in the Mamola bag of tricks include near-vertical wheelies, nosestanding stoppies and spectacular, tire-smoking broadslides, all of which have helped Mamola become a darling of the fans. “It’s good for Cagiva and it’s good for racing,” he says. “Like last year when I was sliding on the old Pirelli tires in Brazil. I could flick that thing around anywhere, the (rear) tire was so bad. When I shut it off it would go sideways and I had to gas it again just to keep it going. It was fun.”

With more-competitive Michelin tires and a rapidly improving bike. Mamola probably won’t be playing around quite as much the rest of this season: He has a real chance of getting himself and the Cagiva back in victory circle. But there’s always time for a little clowning. “I want to have a pair of leathers made like an old pair of pajamas, the western style with the trapdoor in back, and wear nothing underneath. Then I’ll go down the straightaway and open them up,” he laughs.

It probably won’t help him win any races, but like most things Mamola does, wearing his new set of leathers will certainly win the hearts of the crowd and his fellow racers. And perhaps that’s the victory that Randy Mamola treasures most of all.

Clipboard Incas Rally, take three

For the third year, Acerbis Plastica put together its Peruvian Incas Rally in the mountains of South America. And once again, it was more of a contest of survival than a race. Among the notable DNFs of this year’s event were the only two American entries, former U.S. Enduro Champion Kevin Hines and 50-year-old Sidney Dickson. Also not surviving were former World Motocross Champion Heinz Kinigadner and former Paris-to-Dakar winner Edy Orioli. Who did finish? About 40 riders, including winner Angelo Signorelli. That makes it three wins for Italy in the rally.

Luck struck

tgYou can’t have all good luck. Eventually, something has to go wrong,” said Honda rider Jeff Stanton after the final round of the 250cc outdoor motocross championship at Troy, Ohio. But this year, even when Stanton has bad luck, he still has a pretty darn good day. In the first moto, he crashed, got fourth and still bagged the 250 national championship. This comes one month after he clinched the national supercross championship.

Will Stanton be able to maintain his domination after Rick Johnson and Jeff Ward fully recover from their injuries? “I think so,” says Stanton. “I’ve got momentum now— I’ve learned a lot.”

Stanton will get the chance to put that confidence to the test when he and a healthy, hungry group of racers gear up for what should be the closest 500 national series in years. Stay tuned.

Flying Fred Merkel flies home

F red Merkel won the world Superbike championship last year by being consistent, and this year he’s doing it again. For the first time ever, the series came to the U.S., at Brainerd, Minnesota, and going into the race, Merkel and his Flonda were the ones to beat. He had just won the Canadian round in Mosport and was looking to make it a doubleheader.

But Raymond Roche and his Ducati had other plans. Superbike rounds each have two individually scored legs per event, and Roche won both legs at Brainerd, leaving Merkel with a third and a fourth. Merkel still leads the points after eight legs, with 126 points to Yamaha rider Fabrizio Pirovano’s 105. With 14 legs left, anything can happen. But the smart money is on Merkel to finish on top.

GP notes

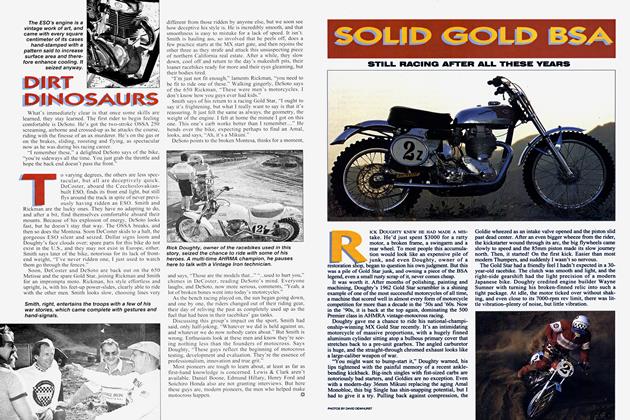

It's been one of the weirdest roadracing GP seasons in recent memory. The latest drama unfolded at the Belgian Grand Prix, where the race was started and stopped three different times due to rain. Eddie Lawson was leading the first two times the checkered flag fell; Wayne Rainey the third. After the race, an FIM jury declared the third leg of the race void (the FIM only has provisions for two-leg races in its rulebook). That made Lawson the winner, though he was awarded only half the usual points. Rainey’s Team Lucky Strike appealed the ruling and now official results are pending.

In the next race, the French GP, Lawson scored a less-controversial win and earned a full 20 points at Le Mans, a course that has treated him poorly in the past. “Two years ago, I really suffered a case of brain fade when I crashed on the very first lap in pouring rain,” Lawson said. His better performance this year puts Lawson within striking distance of series point leader Rainey. M

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

October 1989 By David Edwards -

Columns

ColumnsAt Large

October 1989 By Steven L. Thompson -

Columns

ColumnsLeanings

October 1989 By Peter Egan -

Letters

LettersLetters

October 1989 -

Roundup

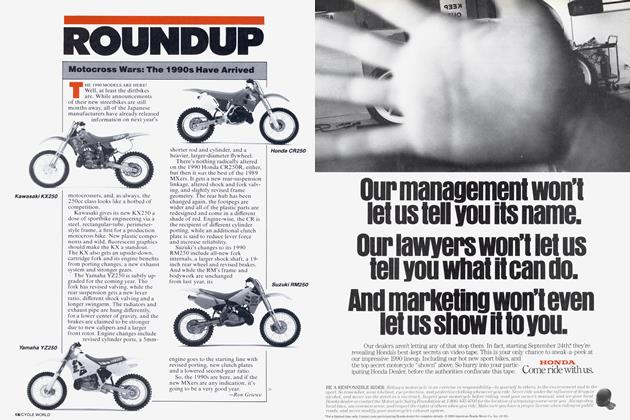

RoundupMotocross Wars: the 1990s Have Arrived

October 1989 By Ron Griewe -

Roundup

RoundupThe Harley-Davidson Success Story

October 1989 By Jon F. Thompson