Honda and Kawasaki beef up the budget dual sport class with a pair of 300cc machines.

September 1 2021 ANDREW OLDARBORED AND STOKED

Honda and Kawasaki beef up the budget dual sport class with a pair of 300cc machines.

ANDREW OLDAR

Feel like going outside more these days? Yeah, you and everybody else. Of all the changes since the pandemic began, people wanting to get out and adventure is one of the biggest shifts. Naturally, there’s no better way to do that than on the pegs of a motorcycle. That’s likely why the dual sport segment enjoyed the highest sales gain of any single category in the last year, with purchases up 47 percent over 2020 according to the Motorcycle Industry Council.

And the dual sport segment has a broader selection of machines than ever. That’s thanks to ultra-high-performance street-legal dirt bikes, from the top-flight KTM 500 EXC-F to the economically priced Honda CRF300L and Kawasaki KLX300 we’re comparing here. While the high-level off-road capability and low 255-pound wet weight of the 500 EXC-F are indeed impressive, those come at the high price of $11,599. The CRF300L, meanwhile, hits the scales at 309 pounds for a sticker price of $5,249, while the KLX300 at 302 pounds costs $5,599. The 300s aren’t exactly featherweights. But they’re less than half the cost of KTM’s flagship, leaving budget room for fuel, oil changes, new tires, and personalization with aftermarket parts. The Honda and Kawasaki can’t be modded to be as dirt-capable as the 500 EXC-F, but they’re in a different subcategory of the dual sport segment: small-displacement commuter/playbikes.

Both the CRF300L and KLX300 are updated for 2021, with engine displacement being the most notable change. Each manufacturer has its own approach to bumping engine size; Honda increased the stroke of its outgoing CRF250L by 8mm, while Kawasaki gave its former KLX250 a 6mm-larger bore. Hence the 286cc and 292cc displacements, respectively, and the model name changes, rounded up to the nearest hundred.

We chose these bikes not only because of their recent overhauls, but because they’re easy to ride, excellent commuters, feature low seat heights, burn very little fuel, and don’t require deep pockets to purchase and maintain. They might not be your first choice for hardcore single-track trails, but they’re incredibly capable, and would also be a far more inviting option for use as a daily rider or even freeway traveler. Just put a few extra pounds in the tires, top up the tank, and hit the open road.

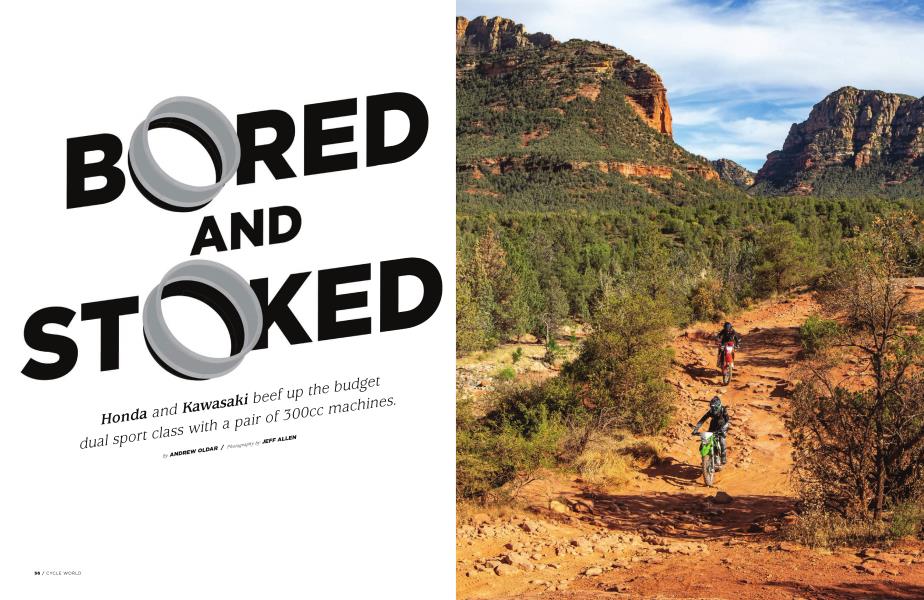

We headed to Munds Park 20 miles south of Flagstaff, Arizona, for our extensive test. The area is blanketed with conifers as far as the eye can see and boasts a vast network of fire roads and two-track trails. That’s perfect terrain for these 300s, especially since we’d be connecting trails with paved roads and highways. We made one deviation from bone stock on these bikes; fitting Dunlop’s Geomax EN91 tires, proper DOT knobbies, to improve dirt traction and ensure consistency between the bikes.

Our Arizona crew was rounded out by guest tester Evan Allen and his father Jeff, incidentally our staff photographer. As if three days of saddle time in Arizona weren’t enough, we put additional miles on the machines after getting back home, making sure no stone was left unroosted in the testing process. Allan Brown, whose career includes stints as a pro Supercross and motocross technician, engine builder, team manager, and even a team owner, helped put California miles on the bikes.

Our ’zona HQ was a rented vintage A-frame cabin surrounded by pine trees. Our first ride out was a highway run to beautiful Sedona. The first things we noticed after merging onto Interstate 1 7 were the dashboards. Both bikes feature a tachometer, odometer, two tripmeters, and clock. While the KLX300 has lights that illuminate when the bike is in neutral and low on fuel, the CRF300L has an actual fuel-level gauge and gear position indicator. The Honda’s dash screen is also taller, allowing for larger gauge-face numbers, which testers found easier to read.

After a few miles on asphalt the pine trees slowly disappeared with the gradual decrease in elevation, so we transitioned to dirt. Massive red rock buttes emerged in the distance. The fire road was plenty wide with sections littered with small rocks, some embedded in the ground and others willing to move; a sheer drop to our right kept us on our toes. The circumstances had us stopping every now and then to appreciate the view, rather than splitting our focus between the incredible scenery and the terrain directly in front of us. The Honda’s suspension shined, absorbing the rocky low-speed terrain with more comfort than the Kawasaki’s, which was not as plush through the initial portion of its stroke and also slightly firmer overall, making it harder to maintain a straight line. The tables would turn later that day. After reaching the pavement, battling Sedona traffic, eating lunch at Cowboy Club Grille & Spirits, and squirming our way back to our bikes through tourist-ridden sidewalks, we social-distanced ourselves from the other out-of-towners to explore Sedona’s off-road areas.

We set our sights on Van Deren Cabin, a pair of oneroom Arizona cypress log cabins connected by a metal roof. Once the home of cattle rancher Earl Van Deren and family, the cabin is now owned by the Forest Service and accessible to the public by a short walk from the end of the trail. It seems like it’s far from civilization, yet a luxurious golf course home is visible not far from the cabin.

Searching for the smoothest lines to and from Van Deren Cabin on the wide and somewhat rocky 2.5mile dirt portion of Dry Creek Road gave us a taste of the bikes’ handling. The Kawasaki, aided by its narrower and smaller overall feel, was a touch quicker to change direction with footpeg pressure. Speaking of footpegs and pressure, the green machine’s platforms are certainly smaller than the Honda’s and concentrate more pressure on the rider’s feet; it’s like standing on a piece of rebar.

The Honda was roughly comparable to the Kawasaki in terms of handling. But its additional 7 pounds plus a wider cockpit area, including radiator shrouds, midsection, and seat, combine to make it just a touch slower to maneuver. It may not be as slim as the Kawasaki, but testers praised Big Red’s ergonomics.

“As far as fitment and rider triangle, the Honda felt bigger and roomier,” Allen said. “It’s a lot closer to the feel of a full-sized off-road bike.”

Returning to the paved portion of Dry Creek Road, we rode south on state Route 89A to Outlaw OHV Trail. Pausing by a lone tree in the middle of the desert, we were greeted by a panoramic view of the mountain range we would spend the next two days exploring. With sunset quickly approaching, and with our increasing familiarity with the territory, we hastened our pace on the dirt road back to the highway.

Faced with larger bumps at higher speeds, the Kawasaki’s KYB 43mm inverted fork and KYB shock delivered a controlled high-performance feel. Helping it remain stable at speed was an impressive amount of what we sometimes describe as “holdup.” So what’s holdup? Think of it as the ideal combination of stiff-enough spring rates with good compression and rebound damping; together, this gives the suspension excellent bottoming resistance and the ability to absorb repeated bumps without packing down in the stroke, where the suspension becomes too compressed to respond efficiently. “Holdup” is why test riders could push the Kawasaki further and harder without the bike becoming busy or unpredictable.

The faster-paced terrain also brought out the Honda’s most glaring weakness: a too-soft overall suspension setup. This was particularly pronounced in the shock, which made the rear of the bike ride low, occasionally blowing through the stroke and occasionally even bottoming on larger and heavier impacts such as G-outs. This in turn caused an unnerving rebound effect that threw riders forward. As no damping adjustments are possible on the Honda’s 43mm Showa inverted fork and Showa shock, testers found themselves backing off and slowing down when presented with challenging high-speed terrain.

This was true on both Arizona and California trails. “The Honda’s suspension is more suited for pavement and mellow dirt roads,” Brown said. “The lack of any adjustability is a large disadvantage. The shock damping and spring rate are too soft, causing the rear of the bike to ride low. And I am only 1 70 pounds. I can’t imagine what it would be like for someone above 200.”

We’d had our fill of Sedona’s desert landscape, and our second riding day took place at the higher elevations above Flagstaff. Exiting the highway, we found a Forest Service road and passed by campgrounds of people enjoying the outdoors. While stopping briefly to chat, we noticed our boots had worn the CRF300L’s frame paint down to bare metal above the footpegs.

Not a knock on the bike’s performance and inevitable after extended dirt riding, but this happened a bit more quickly than we’d expected.

Our 13-mile ride south from this point has to be one of the most scenic in the country. Gorges lined with pine trees attempted to distract us as we negotiated countless switchbacks down the canyon with drops not far to the side. The descent made it clear the Kawasaki’s front brake had better feel, with a nice progressive bite and more stopping power. Although the Honda’s front brake worked acceptably, it had a firm lever with little to no progressiveness. Both rear brakes were about equal.

“The only thing holding the Honda back for me is the suspension

Parking our bikes just off the side of the road in Oak Creek gave us a chance to cool off at a swimming hole, and with our appetite built up by jumps from high rocks into the refreshing water, we headed to lunch at the Butterfly Garden Inn Market Cafe to enjoy sandwiches while sitting on the back of a vintage fire truck. Rejuvenated, we battled tourist traffic along scenic state Route 89A once again, heading north and gaining elevation on the way to East Pocket.

It was a 23-mile ride at thirdto fifth-gear speeds through pines and meadows on smooth dirt roads. Upon arriving, we immediately understood why East Pocket is also called “Edge of the World.” Here, the vast, conifer-covered high plateau that Flagstaff and surrounding sit on dramatically drops away to expose the lower, red rock country where Sedona lies. While taking in the breathtaking views, we paused a moment to appreciate the variety of terrain and incredible places we had ridden in such a short amount of time aboard these relatively inexpensive motorcycles. They can take you just about anywhere, are more capable than any Jeep, and deliver cost-effective fun. You have to travel light, but that’s part of the fun.

Day three began with familiar territory to access some different routes, taking Interstate 1 7 to Kachina Village, Forest Road 237 to state Route 89A, and FR 231 to FR 538. Riding at 6,400 to 7,200 feet of elevation demonstrated that the Honda’s engine was superior to the Kawasaki’s; stronger, smoother, with more torque in the low-to-mid-rpm range and significantly better shifting. Conversely, the Kawasaki powertrain’s weakest link was the gearbox; it was clunky and difficult to shift. The green machine’s powerplant was simply adequate overall, running well and making impressive power for a dual sport of its displacement. But the Honda engine was simply better in all categories.

Running the bikes on our in-house dyno confirmed our engine testing feedback. The CRF300L makes more horsepower and torque than the KLX300 from 2,500 rpm to 3,200 rpm and 4,500 rpm to 7,700 rpm. From that point until both engines hit the rev limiter, the Kawasaki surpasses the Honda in horsepower and torque, giving the green machine the peak horsepower advantage of 23.4 hp at 8,100 rpm compared to Big Red’s 22.7 hp at 8,400 rpm. Most peak torque belongs to the Honda with 1 6.7 pound-feet at 6,400 rpm versus the Kawasaki’s 15.4 pound-feet at 8,000 rpm.

Arriving at the entrance to Turkey Butte Lookout, we were disappointed to find a closed gate. We left to take a slightly different route, which resulted in our taking a short break in the company of some cattle. We then looped back to visit East Pocket again before a fun dirt and highway ride back to the cabin.

Our final ride took place at sunset and was the most technical of the trip. Frog Tank Loop, a two-track OHV trail, was littered with small rocks and weaved through the pines. This technical terrain called for first and second gear in many areas, with clutch feathering conditions in its most difficult parts. Although the Kawasaki’s clutch pull was by no means strenuous, it certainly seemed that way when compared to the Honda’s, which is certainly the easiest cable-actuated pull of any full-size off-road motorcycle I’ve ever ridden and rivals a trials bike in terms of effortless lever pull. That’s especially impressive considering a clutch on a trials bike is hydraulic, specifically designed for constant use that doesn’t tire the rider’s hand.

The Honda continued to stand out in tight terrain.

Its gap between first and second gear was noticeably smaller than the Kawasaki’s, allowing easier riding in second gear through the tighter sections where the KLX300 worked best in first. Second gear was possible on the green machine in such areas, but only with a finger on the clutch at all times, and a busy finger at that. After a few minutes of this, we found ourselves downshifting the Kawasaki to first to give our index finger a break. The Honda’s lower second gear also allows easier acceleration from a stop. In the same scenario on the Kawasaki, more clutch slipping is involved. Third through sixth gear on each bike was comparably spaced.

2021 HONDA CRF300L

$5,249

2021 KAWASAKI KLX300

$5,599

Our 365-mile ride in Arizona and subsequent 1 50plus miles in California gave us a great understanding of the CRF300L and KLX300. But didn’t necessarily give us a cut-and-dried answer as to which machine is the hands-down best. Both excel in different areas.

The Honda is the better commuter and fire-road ripper in stock trim. If its suspension was 1 5 percent improved to give it the holdup needed to handle gnarHer off-road conditions, it would be the undisputed winner. It’s priced $350 less, so that money could go to a suspension shop respringing or re-valving the Showa components.

A notchy gearbox, large gap between first and second gear, and more difficult clutch pull are the main drawbacks of the Kawasaki. But its fundamental weak points are that it’s less refined than the CRF300L and feels like an older motorcycle. Despite that, for a rider whose off-road aspirations go beyond smooth fire roads and mild two-track, the KLX300 is the more capable bike off the showroom floor.

So before you go outside on one of these bikes, look inside yourself. Understanding your mission when you make your decision will let you enjoy the remarkable capability and value of these bikes as you become part of the dual sport boom.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

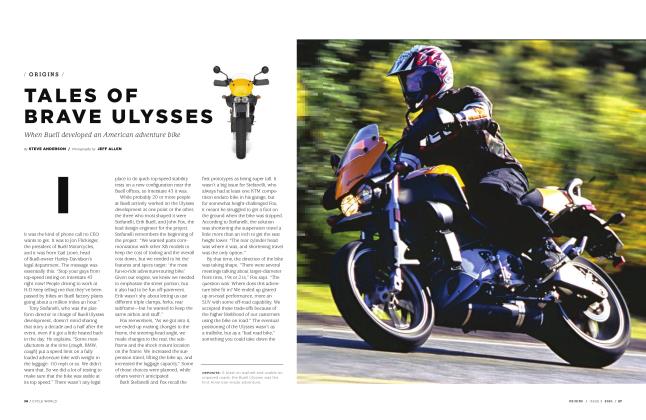

ORIGINS

ORIGINSTALES OF BRAVE ULYSSES

Issue 3 2021 By STEVE ANDERSON -

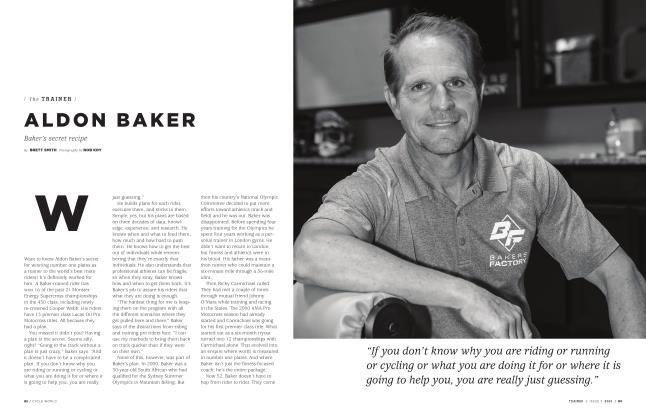

The TRAINER

The TRAINERALDON BAKER

Issue 3 2021 By BRETT SMITH -

CALIFORNIA TT

Issue 3 2021 By MICHAEL GILBERT -

TDC

TDCIN THE STYLE OF THE TIME

Issue 3 2021 By KEVIN CAMERON -

ELEMENTS

ELEMENTSTHE ELEGANT SOLUTIONS

Issue 3 2021 By KEVIN CAMERON -

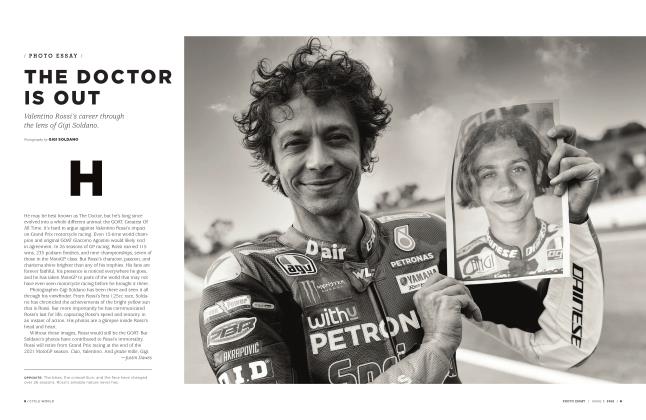

PHOTO ESSAY

PHOTO ESSAYTHE DOCTOR IS OUT

Issue 3 2021 By Justin Dawes