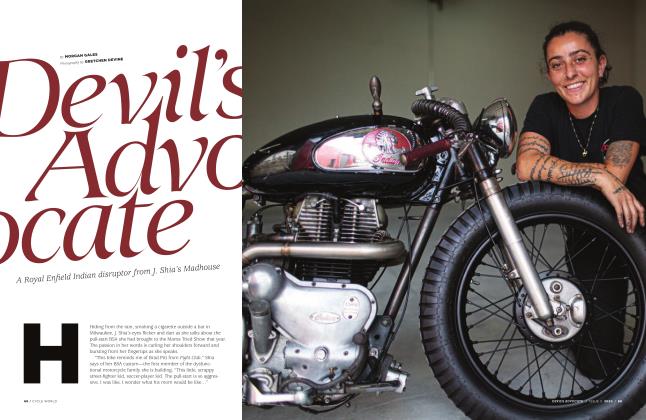

FOREVER YOUNG

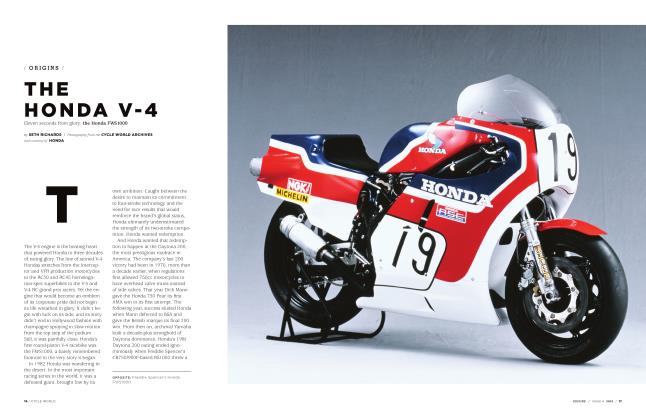

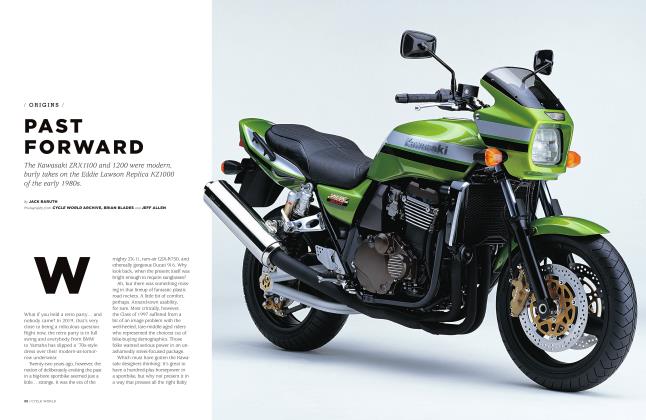

ORIGINS

The 50-year saga of Harley-Davidson’s XR-750

ALLAN GIRDLER

Before we can truly appreciate Harley’s ageless wonder and its half-century of winning and losing, we must hit the way-back button all the way to 1968 and the annual meeting of the American Motorcyclist Association’s competition committee.

They had a problem. For 30-plus years, the AMA’s national championship had been contested by bikes powered by side-valve 750s or OHV 500s. The rivals were roughly equal in performance, were the sporting models of their day, and were what Harley-Davidson, Indian, and the English importers had to sell. The world’s economy was in ruins and the sport was nearly dead; and anyway, this equivalency formula had provided years of close and fair racing.

But that was then. Now—in 1968, that is—the 750 side valves and OHV 500s no longer duked it out at the top of the heap.

Therefore, the committee voted for production bikes, made in fleets of 200 or more, limited in modifications suitable for racing.

The English were ready, with a variety of sporting 650 twins.

The Americans, that is HarleyDavidson, were not. Their challenge to the Brits’ 650s was the 883cc Sportster, and anyway, the Motor Company was in financial trouble.

By lucky chance, that 1934 formula had an exception: an open class for TT, which was supposed to attract the big twin back then. In 1968, H-D had a stripped Sportster, the XLR.

The racing department did what it could. It developed a destroked, to 747cc, version of the XLR, fitted with larger valves, magneto ignition, and a single Tillotson carburetor.

It’s worth noting here that Harley did not make all its racing parts; it made the engines and designed the frames, but ordered frames and the fiberglass tank and seat (and fairings for the roadrace XRTT) from reliable suppliers, and used top-quality suspension, as in Ceriani forks and Girling shocks, then it assembled and tested the finished machines, to be sold to the public through the H-D dealer network. “Race what you sell and sell what you race” would be the slogan today.

Oh, and the Harley racers had to look like Harleys.

The new rules—750 four-strokes for miles, half-miles, TTs, and roadraces; 250cc singles for short track— went into effect in 1969.

Harley-Davidson wasn’t there, not having built all the 200 examples in time.

So, in the lobby of the Houston Astrodome at the opening of the 1970 Grand National season, a production XR-750 was parked.

The engine’s left side case half was stamped “1C1” for competition engine, then the serial number followed by “HO” for 1970, the eighth decade of the 20th century, all in Railroad font, which is tough to copy.

The XR introduced there was as clean, functional, and attractive as any motorcycle ever made, and no one has improved on that profile. That said, next must come the fact that the original XR-750 was a mitigated disaster.

First, disaster. Although H-D had been fitting its big twins with aluminum heads since 1948, the XR used iron heads and barrels, as in the XL series. The reworked version made too much heat, not enough power, and broke down, as witnessed at the 1970 Daytona 200 when all the team bikes dropped out.

Something like 100 iron XRs went out the door, followed by factory bulletins telling the new owners how to improve the handling and reduce heat by reducing power. Sorry, but that’s the truth. They won a few races before the next chapter began.

That is the alloy chapter, bikes arriving early in 1972, not quite early enough to make the Daytona circus. The new and improved XR750’s heads and barrels weren’t merely aluminum; they were some sort of space-age mix. Engine cases and the transmission were mostly carry-over, but the bore was wider and the stroke was shorter, the flywheels were one-piece forgings, each cylinder got its own carburetor, the gear case (as H-D calls where the camshafts go) still had the four single shafts in a wide vee, with roller lifters, pushrods, and rocker arms.

Repeating a theme here, the ’72 XR was offered to the public; OK, it helped if you held an expert license and knew a dealer who liked racing, but the business plan was the dealer sold you the bike. The dealer had a parts book, and he got the parts for you ’cause the competition department did not sell direct.

No names here, but at least one of racing’s heroes won titles with the only factory machine in the series, the other riders being sponsored by themselves and riding bikes prepped in the backyard.

The XR-750 has been the exact opposite.

The AMA Grand National Championship (and now American Flat Track, or AFT) has always been close; witness Mert Lawwill winning the 1969 title with his KR, Gene Romero getting the No. 1 plate in 1970 on Triumphs, and the 1971 title going to Dick Mann and his BSA.

And then we had 1972, won by Harley teamster Mark Brelsford. There were some bridesmaids, so to speak, with Cal Rayborn winning a roadrace with a wildly modified iron XR and Brelsford using his 300-pound, 100 bhp XLR to finish fourth in the Houston TT. The new XR was as good at its debut as the iron XR had been at its retirement, and a match for the Triumphs and BSAs and Nortons.

And then the world shifted, if not turned upside down. The rules by this time allowed pretty much any mod you cared to make while Yamaha was selling squads of 350 racing twins—and let slip that it would make 200, yes 200, 700cc two-stroke four-cylinders.

We also got great racing, and a series of heroes.

Yamaha had the best selection, with 650 twins for miles, halfmiles, and TT, motocross-powered singles for short track, and the all-conquering TZ750 for roadraces.

Kenny Roberts won the series in 1973 and ’74, while in the other camp, the last of the 1972 XRs went out the door, so in 1975, the racing department built 100 new XRs, using frames from Terry Knight and Mert Lawwill, and incorporating another major improvement that led to 85 bhp, up from the 73 of 1971.

The 1975 title went to Gary Scott, a loosely backed member of the Harley team who was allowed to ride a Triumph in TTs. It started a long string of championships for the XR and introduced us to some of the big names in the canon. For example, Jay Springsteen, who won from ’77-79 with ex-Scott tuner Bill Werner, already accomplished but a future legend.

This isn’t in sequence, but it is a good time to remind XR buffs that between the introduction of the XR in 1970 and the shipment of the last factory-spec frame in 1989, the XR went from magneto to CD ignition, one plug per cylinder to two, timed oil-pump breather to Bill Werner’s mini sump, roller to Superblend main bearings, and then from one to two per side, at least two mixes of alloy in heads and barrels, wasted spark to single fire, and intake ports from round to oval. Former team tuner Steve Storz came up with an unbreakable (well, nearly) crankpin, Werner perfected the Twingle, with both cylinders firing on the same revolution, alloy barrels to alloy plain to alloy nickel-plated... Suffice it here that if you park a 1970 XR-750 next to a 1990 XR-750, they will both click right into the image most of us carry for the bike in our minds, no matter what era we were watching competition.

Now then, back to racing history. Honda first followed the spirit of the rules and made major changes to the CX500 in the early ’80s. Not even Freddie Spencer could make the thing work. Late in 1983, Honda went from the spirit of the rules to the letter of the law.

Its competition department bought at least one XR-750, and its designers took everything apart and did what Harley would have done if Harley-Davidson had Honda’s money; that is, it designed a fore-and-aft V-twin, 45 degrees, but with overhead camshafts and four valves per cylinder. When the factory’s frame disappointed, it got a better version from C&J. It hired retired champ Gene Romero to run the team, and he scooped up both winners for other teams. And the riders? Upcoming Texan Bubba Shobert and, yes, Ricky Graham, a championship winner with Tex Peel tuning on an XR in 1982. On a Honda, Graham won the series in 1 984, and Shobert likewise in 1985. Quoting Graham here, the RS750s “are just a better bike.”

At this point, two other developments: One, the AMA was concerned with Honda’s achievement. Seems Harley fans didn’t want to watch losing, and Honda fans didn’t care about winning dirt track as opposed to superbikes or motocross. Oh, and the best Hondas and Harleys were burning up the tires of the day, to the extent that GN races were shortened.

Tests by airflow expert Jerry Branch showed an average XR-750 to deliver 92 bhp, ditto a stock RS750, while a Werner-tuned XR had 100 bhp, and an RS by Hank Scott cranked out 107 bhp.

The AMA’s solution? Restrictor plates for the Honda and Harley 750s, and WOT for the converted 650 twins. (Watch this space.)

Two, Harley-Davidson was in deep financial trouble in 1985, so it shot down the racing division. It let Randy Goss go. Springsteen and new kid Scott Parker were given bikes and parts and a budget, and told to hire their own tuners and crew.

Parker, like Springsteen, was another Flint, Michigan, natural. He earned his expert licenses at 17, the youngest ever, and got his first GN win in 1979.

His 1985 contract said only that he had to hire someone of proven competence. He offered the job to Bill Werner, at the time one of the two men keeping the racing shop’s lights open. H-D management said he couldn’t do it. Parker’s attorney suggested that H-D’s attorneys read the contract again.

Werner got the job, and got to do his work at home.

Why did this matter? Because when Werner worked for the racing division, he shared his discoveries. When he worked for Parker, he kept his finds to himself.

The result: Parker won 94 GN races and nine national championships, five in a row, adding up to several records almost certainly not to be broken. He retired from the team in 1999, came out for fun in 2000, and got his last win at the legendary Springfield Mile.

Sometime in here, Honda quit dirt track to concentrate on roadracing and motocross. It quit cold; no more parts. Thanks, guys.

In contrast, in 1990, H-D’s revived sort of racing division commissioned 90 new sets of cases for the XR750. Rewarding this good deed, the machining was off just a bit here and there, and the project had to be redone in a major loss of face.

The next hero here was Chris Carr, who’d been signed as the next top gun, which he proved to be; Werner having not returned to the team, Carr signed on Kenny Tolbert, another deep-thinker. Using his XR750, he won the title seven times.

Honda’s invasion shook the AMA competition staff into action, and they’d drafted a new equivalency formula, with large-displacement road-bike engines limited and smaller twins unrestricted, with the purpose-build Harley and Honda racebikes still running restrictor plates.

No surprise that Werner worked out that it is better to improve the small engines than handicap the large ones. He built a low-buck Kawasaki 650 and, hey presto, the Werner Springsteen Racing Team, yes that Springsteen, with Brad Smith up, won the 2010 Indy Mile.

More good racing followed, with Kawasaki and Harley closely matched, but with Yamaha, Ducati, and Triumph racers also involved.

This gets complicated. Polaris Industries revived the classic Indian name, the AMA shifted professional dirt track to American Flat Track, which invented a bunch of new classes, and Harley brought out a new line of XG street twins—watercooled, fuel-injected, etc.—in 500cc and 750cc form.

There was a lot of team realignment, with Smith, Brad Baker, and Jared Mees winning national titles for Harley, Kawasaki, and Indian, the most important for us being the 2016 Indy Mile in the XR-750’s final team appearance.

The Motor Company has always tried to race what it sells and sell it to the racers, so when the (finally) revived Indian said it had commissioned a race-only 750, the guys at Harley let slip they had racing in mind when they drew up the new 750—to scant avail, sad to say. Specs for the two are similar, but since Indian’s FTR750 arrived, it has ruled the roost while the XG750R might as well have been left in the truck.

Why? No one has explained this, but the racing department is not in-house, plus if Werner and Tolbert were still with H-D, things would be different. But that’s personal, eh?

So what for the XR-750? It’s still eligible for GNC racing, and there are enough parts and expertise inside the factory and out to ensure that you will always dare to start your XR750, assuming you have the scratch to buy one.

As a distant hope, recall that back in 1969, when the 750 went into action, and the Brits were ready and H-D wasn’t, two-time No. 1 Gary Nixon showed up for the Nazareth, Pennsylvania, mile with a shiny new Triumph OHV 750, everything up to date.

Harley teamster Fred Nix, not one to experiment, opted for his KR with rigid rear and no brakes.

Nix won the main by half a straight.

“What happened?” the stunned crowd asked.

Nixon could dish it out—and he could take it.

“I got beat,” he said.

It could happen again.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue