The First Superbike

Fifty years of Honda CB750, the motorcycle that changed the world

April 1 2019 Kevin CameronFifty years of Honda CB750, the motorcycle that changed the world

April 1 2019 Kevin CameronTHE FIRST SUPERBIKE

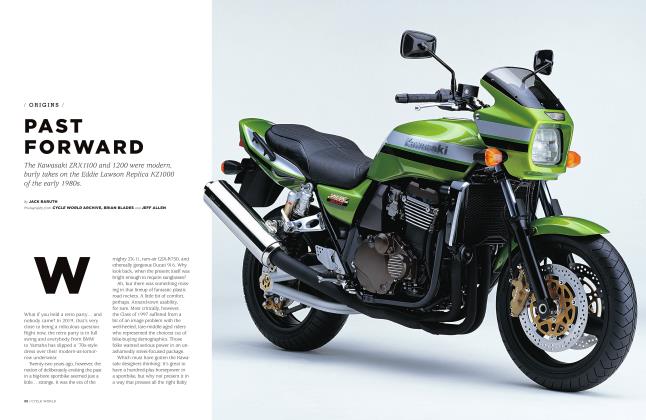

ORIGINS

Fifty years of Honda CB750, the motorcycle that changed the world

KEVIN CAMERON

The present era of high-power, multi-cylinder superbikes began with Honda’s four-cylinder CB750 of 1969. It was a natural in the marketplace because the company had invested nine years in international Grand Prix roadracing to make Honda a household word worldwide. When an electric-start motorcycle with four cylinders and four boldly jutting exhaust pipes hit the market, its success was foreordained.

Four-cylinder machines had been successful in roadracing before—the Italian fours of Gilera and MV— and there had been four-cylinder production bikes as well, such as the Belgian FN and American Indian four. But nothing like the complexity and power of this new Honda had ever been offered for public sale.

CB750 power was the result of the same principle that had made Honda fours so successful in racinghigh rpm made possible by cylinder multiplication. England’s racing singles reached high sophistication but their long strokes limited their rpm. By using greater numbers of smaller cylinders—each with a short stroke—Honda had pushed beyond 21,000 rpm in racing by 1967. That meant that the CB750’s 67 claimed hp at 8,000 rpm was achieved without strain, although this rpm level was out of the reach of the most powerful of British parallel twins.

“It is hard to keep from raving at the way the hardware on the chassis has been arranged to allow what must be the ultimate angle of lean for any big-bore.. .It is nearly impossible to ground the 750, which allows as much, or more banking than the Superhawk. ”

— Cycle World, August 1969

The world motorcycle community was stunned that it was possible to offer this level of sophistication— four cylinders, single overhead cam, a disc brake, and electric start—at a price of $ 1,495 that guaranteed large sales. More than 400,000 would be built over 10 years.

By the end of World War II, Japan’s industries were destroyed. Starting over, they began not with the 1930s technologies that in the 1950s produced most of the world’s motorcycles, but with the latest in automated equipment.

Japanese products were thoroughly engineered for rapid assembly, and the CB750 in particular also benefited from automotive techniques. Instead of crankshafts assembled from many pieces, then made straight by skilled handwork, the CB750 had a one-piece steel crank, spinning in durable, long-lived plain bearings. To speed its build on the assembly line, the CB750’s crankcase was horizontally split, allowing crank, gearbox shafts and other internal parts to be set sequentially into its upper case, then enclosed by the lower case half.

Honda engine assembly did not depend upon fussy, time-consuming heat-shrink fits.

Honda’s market research in the United States revealed that American buyers were most comfortable with tubular steel chassis rather than the pressed steel of many early Japanese models. It was known that American riders wanted a comfortably muscular look backed by plenty of power. The information was good, so the bold step up from the hunched-over styling of the moderately powerful CB450 of 1966 to the instant dominance of CB750 in 1969 was a success.

Honda had followed the market methodology of General Motors’ Alfred P. Sloan, who created an “economic ladder of models,” beginning with the plain-jane Chevrolet and extending upward to the luxurious Cadillac. Chevy owners stretched their credit to reach upward to Oldsmobile. The first Hondas— bikes such as the 50cc Super Cub and the electric-start pioneer Benly 125cc twin—led to a proliferation of models, always tempting riders to move up.

Ever since company founder Soichiro Honda had successfully used research to make his first product—piston rings—successful, he had invested in equipment for R&D and product testing.

In common with other Japanese firms, Honda had embraced the techniques of statistical process control; summed up in the words of famed manufacturing consultant Dr. W. Edwards Deming: “an increase in quality is an increase in production.”

Use of a standard 2,000-hour vehicle-life test made Honda motorcycles known for reliability.

"Your Honda dealer will have it soon. The Honda 750 Four. When you twist the throttle, remember one thing. You asked for it."

— Honda ad, 1969

In 1970 Dick Mann won the Daytona 200 Miler on a CB750 Honda factory-modified for racing.

CB750 was the first motorcycle to be described as a “superbike,” and competing brands soon entered the market—Kawasaki’s four-cylinder 903cc Z1 in 1973, and Suzuki’s GS series 750 and 1,000cc fours three years after that. All this made the 1970s a feast for motorcyclists.

Even with its remarkable 123.24mph top speed recorded by Cycle World in its 1969 road test, the CB750 today seems simple and unsophisticated, being air-cooled with only a single overhead cam, two rather than four valves per cylinder, separate pipes and a conventional drum rear brake. It was a bold experiment that had to succeed at the first try, and proved further complexity could be added in step with market demand.

Succeed it did, opening the doors to a new kind of motorcycling that continues its refinement today.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

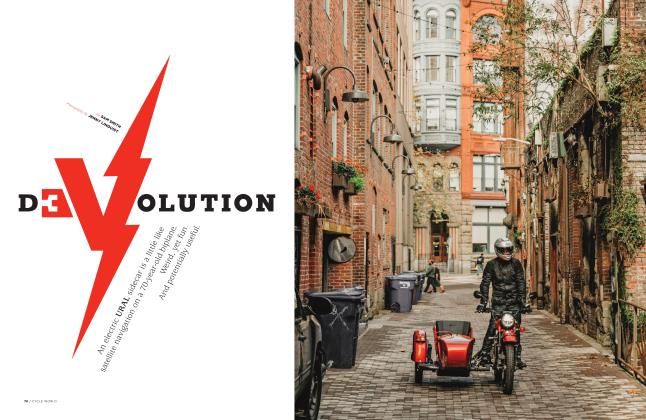

Devolution

Issue 2 2019 By Sam Smith -

Feature

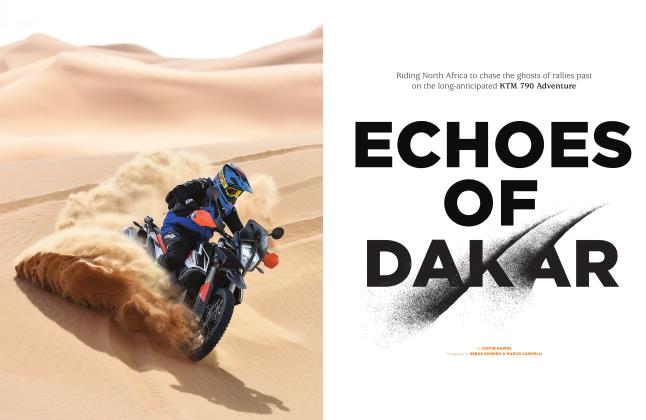

FeatureEchoes of Dakar

Issue 2 2019 By Justin Dawes -

TDC

TDCWhen the Engine Starts

Issue 2 2019 By Kevin Cameron -

Reviews

ReviewsBalance of Power

Issue 2 2019 By Michael Gilbert -

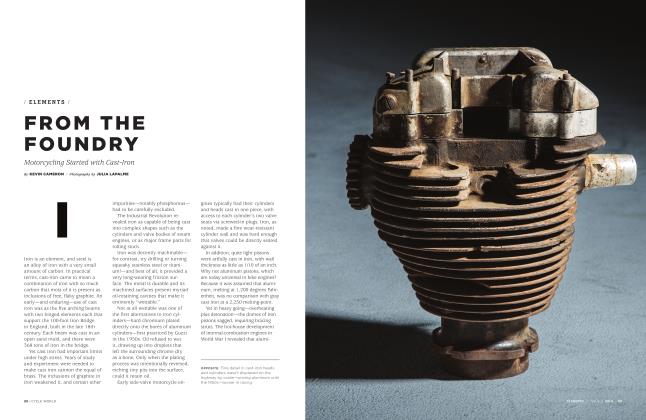

Elements

ElementsFrom the Foundry

Issue 2 2019 By Kevin Cameron -

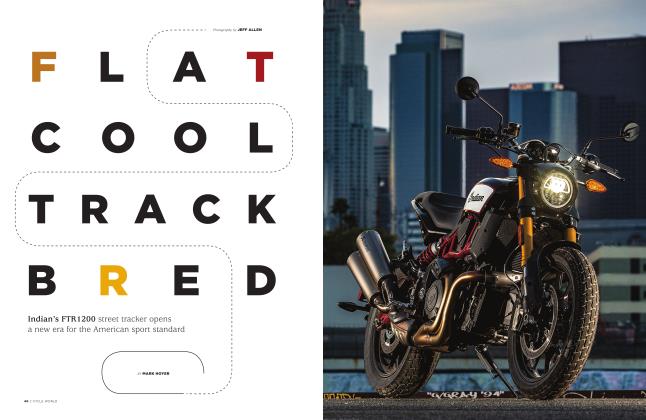

Reviews

ReviewsFlat Cool Track Bred

Issue 2 2019 By Mark Hoyer