Unplug + Play

ALTA MOTORS’ REDSHIFT MX MAKES A STRONG CASE FOR THE ELECTRIC DIRT BIKE

April 1 2017 Steve AndersonALTA MOTORS’ REDSHIFT MX MAKES A STRONG CASE FOR THE ELECTRIC DIRT BIKE

April 1 2017 Steve AndersonUNPLUG + PLAY

ALTA MOTORS’ REDSHIFT MX MAKES A STRONG CASE FOR THE ELECTRIC DIRT BIKE

Steve Anderson

CW FIRST RIDE

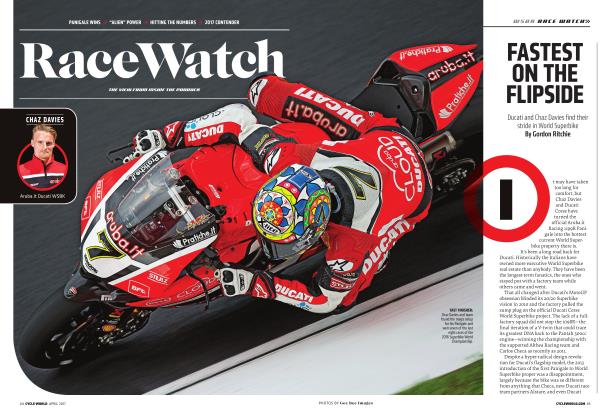

All you have to do is look at the Alta Motors Redshift MX to know: New tech electric device or not, the Redshift was designed by people who deeply know motorcycles. It may have no exhaust system, no gas tank, no kickstarter, no traditional subframe, no engine (!), but this bike looks like a badass MXer—just one that happens to be from the future. Or at least a future.

And so it turns out. Alta Motors was started more than nine years ago with an insight on the part of two friends, Derek Dorresteyn and Jeff Sand, that

electric technology was ready—at least in the narrow world of motocross and off road—to potentially offer a better motorcycle. Sand had been a longtime amateur off-road rider, participating in Hare & Hounds and scrambles events, while Dorresteyn had been a national plate holder in speedway and had raced flat-track and supermoto.

Both came from industrial design backgrounds, with Dorresteyn running a company offering CAD and CNC machine shop services. Working in the San Francisco/Silicon Valley environment, the two were exposed to the electric vehicle technology that was just beginning to jell. Tesla was building its original Roadster, offering acceleration

that was shocking to those who thought electricity was for boring ecomobiles. There was no longer a question that electricity could offer power.

The question was one of range and energy: Could you put enough batteries in an electric MXer to last a pro moto and a little bit more? Dorresteyn did the numbers and found you could—if you were careful with the design and kept the weight of everything else low. By 2009, the two had a design on screen for a 250cc-class e-bike that looks very much like the machine you see in the pictures here and had begun to put together a company to realize it.

Almost every design decision for the Redshift sprang from the desire to build

a bike that was fully competitive with conventional motorcycles. Over the many years from concept to production realization, the battery design evolved (see sidebar), but what stayed constant was that it offered a little under 6 kWh of capacity (enough for a 30-minute pro moto or about two hours of trail use) and weighed less than 70 pounds. That meant everything else had to be light.

With electric powertrains, low weight comes from high efficiency, high speeds, and good cooling. We’re all used to internal combustion engines, where typically less than a third or less of the energy in gasoline goes to the ground, another third heats the air that goes through the cooling system, and

the final third is in the superheated gases coming out the exhaust. With electric, efficiencies are much, much higher everywhere, but the temperature limits are lower.

Lithium-ion batteries deteriorate quickly at temperatures above 150 degrees Fahrenheit, power transistors bake at 185 degrees, magnets demagnetize as low as 200 degrees, and motor wiring insulation fails as you exceed 350. Enter the world of electric machine trade-offs: The more efficient your system, the less heat it generates, and the more power you can push through it. Cool it better, and you can pump even more through.

So Alta chose to design a 350-volt electric system to keep operating cur-

GRANT LANGSTON RIDES THE REDSHIFT MX

A world and national champion roots at Southern California's Pala Raceway

rents relatively low and efficiency high, even if that required more sophisticated, automotive-style safety circuits. Its motor is a custom, brushless, permanent magnet AC (PMAC) design only 4 inches in diameter that spins to 14,000 rpm, putting out either 25 or 40 hp depending on whether you’re looking

at the continuous or short-term power rating. Fortunately, motocross is all about short-term power, with more than a few seconds at full throttle the exception rather than the rule. The motor is actively cooled by circulating oil, but, most importantly, it weighs only 11 pounds—clawing back weight lost to

the battery pack. The torquey e-motor drives the countershaft through a single, direct reduction gear, as it offers peak torque from zero rpm and has no need to idle and no need for a clutch.

Similarly, Alta developed its own motor controller, a water-cooled unit that uses the upper frame for its radiator. The advantages of Alta rolling its own here were several; the water-cooled controller could be a lot lighter and more compact than the air-cooled units on Victory and Zero e-bikes, and Alta would be directly in charge of the firmware that maps throttle position onto motor response. This has been one of the major areas of development for the company, as it writes code that controls throttle response, motor braking, traction control, and all the myriad of functions that dictate machine feel. They’ve been using a wide variety of test riders, from Supercross stars to EnduroCross vets, to tune this. Motor response when twisting the grip had to feel familiar to

Grant Langston was a 125cc MX world champion in 2000 and won the AMA 125cc outdoor championships in 2003 and 250cc Supercross championships in 2005 and 2006. He also went on to win the 2003 AMA Supermoto championship and the 2007 AMA 450cc outdoor motocross championship. He currently runs a multiline motorcycle dealership in Perris, California, works as a riding coach, and is a TV commentator for AMA ArenaCross and outdoor races. We asked this maximally experienced rider to try the Alta Redshift MX.

As he walks around eyeing the Redshift, Langston quickly notices the missing clutch lever: “This thing is going to humble me,” he jokes. “I remember first riding four-strokes and thinking, ‘How do you ride this?’Now it’s getting on a two-stroke again and, ‘How do you ride this?’But this is like going back to school— it’s against the grain of everything I’ve known. No clutch and no gears.”

But after a couple of laps of the fast Pala, California, MX track, Langston has a changed opinion: “It’s nimble and light. Through the sketchy and tight sections, it’s better than a 450 or even a 250; it’s very predictable and comfortable.

You can stop very quickly. With four-strokes, the inertia wants to push you through the bumps. With the Redshift, you can brake pretty hard under braking bumps. The suspension and feel are surprisingly

good.” Grant’s main complaint after his few laps was power-softerthan a good Honda CRF250R, and the front end stayed stuck to the ground. That’s when we tell him the power map is set on 1, the least aggressive. We bump the map up to setting 4, and he wheelies off, almost looping it with the newfound response.

When he comes back in, he smiles, “It’s fun. It went from ‘couldn’t get it up’ to ‘it just stood up.’” The power, he said, was better coming out of sandy corners but still might be a little shy of the better 250s. The initial hit was good, but it didn’t seem to carry that full acceleration for long enough. “Overall, though, it’s good. The braking feels good, the cornering feels good, even standing through the sketchy rough stuff, I feel safe on it.

“I really wasn’t sure what to expect,” he continues. “I wondered if I was

going to be a complete squid. My riding style is always with my fingers on the clutch. I’ve always used the throttle, the clutch, the brakes—dragging them— my whole life. I thought it’d be a tougher transition than it was. It surprised me by how easy it was to get used to. By the time I had done a few corners,

I thought,‘This thing is pretty stable and nimble.’ In a lap or two, I knew it was very predictable and had this sense of comfort because it doesn’t get out of control. It was really cool in that aspect. Maybe because it doesn’t have

the inertia of an engine... Whatever it is, it makes for a nice, fun ride.”

By the time we finished at Pala, Langston wasn’t convinced the Redshift would necessarily be capable of winning there-Pala is a loose track with longer straightaways that rewards top-end power more than almost anywhere else.

“But if you put this thing on a tight, hard-pack track, that’d be interesting. It’s really nimble and gets great traction. There’s no way it feels as heavy as it weighs.” Overall he’s impressed. “It’s a good bike-want to ride it again,” he demands.

riders with a lifetime of experience.

As for the chassis, the emphasis was on sticking with geometry and chassis stiffness numbers that were equivalent to the best of current production machines. The main frame consists of two parts that bolt together: the steering head and upper beam welded from CNC-machined aluminum forgings and a lower casting that houses the e-motor, reduction gear, and countershaft. The countershaft is in the same place as it is on a conventional 250, so the anti-squat forces and rear suspension behavior remains similar to well-developed current bikes. Dorresteyn emphasizes that Alta didn’t want to reinvent everything—taking on the powertrain was more than enough. So he and his team studied the best of contemporary motocrossers carefully. Steering geometry is very similar to a Honda CR250, while the rear swingarm is a one-piece casting that would look at home on a KTM. Suspension is WP at both ends, while brakes are Brembo, the rear controlled by a conventional foot pedal.

The only area of substantial chassis innovation is the two-piece plastic tailsection. Without an exhaust system having to snake through the rear of the bike and heating things beyond the structural limits of plastics, it was possible to forego an aluminum subframe and design one that relied on a particularly tough, fiber-reinforced plastic that could be injection molded. Not only did that save weight and piece cost, but it also was more resilient than a metal subframe, actually acting as a secondary suspension on big jump landings.

One other feature the Redshift has that’s unlike any other motocrosser is its rugged dash. Without engine noise as a cue, the Alta relies on its dash flashing green to let its rider know that the throttle is live and to communicate the state of battery charge.

In the end, though, the Redshift is about the smooth, seamless delivery of power possible with an e-motor and delivering performance that can match or even exceed that of a four-stroke 250. Does it succeed at those goals? At 267 pounds, it is heavier than

a 250 even with a full tank of gas, but it delivers more and smoother torque.

It offers equivalent range to a machine with the small fuel tank of a motocrosser but takes a couple of hours to recharge even if you have the 220-volt charger and a suitable outlet to plug it into. It’s the quietest dirt bike ever and could end noise complaints and track closings if it were to become popular (imagine urban motocross tracks). And at $15,000, it’s among the most expensive dirt bikes around, though the company promises it will make up for a lot of that cost differential by requiring essentially zero maintenance. It’s too soon to say, but if this first serious electric motocrosser is this good, the future probably holds a lot more of them.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue