FROGGER WITH BLOOD

IGNITION

BIKE LIFE

TWENTY POINTS FOR SAVING THE HUMAN

PETER JONES

What is real? We live in a complicated computer age of competing "realities," from gaming to Google glasses. It’s getting harder to know the really real from the somewhat real and the not actually at all real. I’m not the first to suggest this.

I’m unwilling, though, to make a sweeping moral judgment about the “evils” of pseudo realities. First of all, storytelling, ever since its original oral tradition, succeeds only if the audience is willing to believe the unbelievable. The audience must immerse themselves in the tale with complete empathy, picture what’s described, become so emotionally involved that they fidget, laugh, cry, scream, or hoot. When non-motorcyclists ask me how fast I’ve gone on one, they’re thrilled by the answer. I’ve witnessed how a number alone can be worth a thousand words, exciting imaginations.

On the other hand, too much empathy, even with reality, would crush a person. How sad would a heart be that connected with each individual who suffered and died in one year? Or in an hour? A minute? Even at its smallest, such a burden couldn’t be borne by any woman or man. Empathy needs limits.

Yet, we desire the thrill of emotions from stories well told, on a managed scale. Oddest of all, we desire to digitally hunt and kill fake humans or with paintballs and lasers, fake kill real humans.

With technology, storytelling chases perfection, as if trying to eliminate the line between fact and fiction: silent film, sound films, 3-D films, virtual reality goggles... Perception is nine-tenths of the law, and fake becomes more real the more effortless it becomes to believe it.

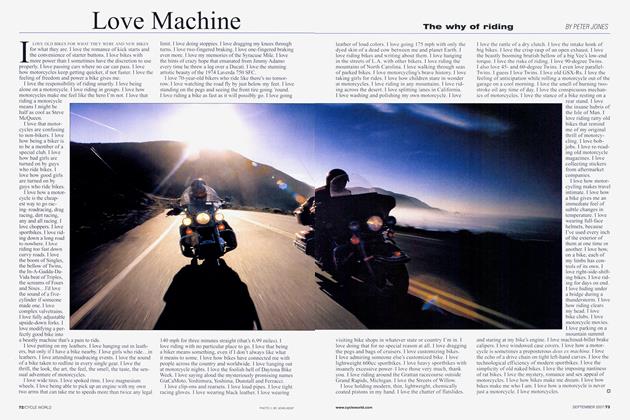

My bet is this warping of reality is why many of us ride motorcycles. On a motorcycle you live in the realest world of all, feeling, sensing as much as you see. Experience is intimate on a motorcycle: the insects, the odors, the waves of warm and cold, the sounds, the feel of motion while sitting on a bike as the world spins by beneath. Motorcycling is always real, if sometimes not a bit too real. It rains and snows outside. And there are cars.

Conversely, it might be that the only intellectually conceptual difference between driving a car and playing a video game is that with a car there’s jail time for mowing people over on the sidewalk. Meanwhile, in the fake reality of Grand Theft Auto death isn’t evil; it’s hilarious.

I wondered about this the other day, while watching a video on the Internet. A motorcyclist with a helmet cam in some Pacific Rim city was heading down the left side of a busy multi-lane street, until noticing an elderly man with a cane trapped in the middle of it. The motorcyclist cut lanes, rode up to the man, and placed himself perpendicular to traffic to block its flow. He did this through each lane until the man reached the curb.

Not long after that I saw a video of a female rider stopping to save a kitten from the middle of a busy intersection. Not a single car stopped.

In both cases, I think the motorcyclist stopped because the highway, the boulevard, and avenue are real places to a motorcyclist. In a car, driving is like watching a movie. Drivers eat, drink, listen to music, watch the funny fake world go outside their windows—windows that with the advent of air-conditioning are no longer ever down. I know normal happy humans who drive in anger. Cars change people. They become spectators, not participants. Car drivers often feel no responsibility for what they witness in the picture show on the other side of the glass because none of it is real. Meanwhile, the motorcyclist is part of that picture show.

I like being in a club that saves old men and kittens.

BY THE NUMBERI

11 HOW MANY POINTS IT TAKES TO WIN PONG

5 NUMBER OF BALLS ALLOTTED TO EACH CAME OF PINBALL

fifty NUMBER OF POINTS EARNED FOR GETTING AFROGGER FROG SAFELY HOME

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMan, Van, Plan

June 2016 By Mark Hoyer -

Intake

IntakeIntake

June 2016 -

Ignition

IgnitionConverted And It Feels So Good

June 2016 By Bradley Adams -

Ignition

IgnitionPre-Ride Techniques the Toys of Summer

June 2016 By John L. Stein -

Ignition

IgnitionThe Knot of Friction

June 2016 By Kevin Cameron -

Klr650 Adventure Time

Klr650 Adventure TimeKiller Tacos

June 2016 By Bradley Adams