Race Watch

ROSSI VS. MARQUEZ LORENZO WINS MICHELIN TIRES SPEC ECU ONE CLASS FOR ALL

THE VIEW FROM INSIDE THE PADDOCK

MOTOGP UNDERCURRENTS

Where we've been and examining the forces in play for the 2016 MotoGP season

Kevin Cameron

The The obvious now-and-future contest in MotoGP is between Honda and Yamaha. Ducati, Suzuki, and Aprilia strive to rise into contention, but only Honda or Yamaha has won a race since 2010.

Contests within the contest are the still-undecided ongoing collision between the 125/250-inspired corner-speed style of Jorge Lorenzo and others on Yamaha and the dirt-track-originated style of the Honda men, Marc Marquez and Dani Pedrosa, which by compressing braking and turning into the smallest distance practicable, leaves the rest of the corner for a quick lift-up and acceleration.

Lorenzo works his tire the whole way around a turn, but the Honda Way is on the tire edges a much shorter time (Dani Pedrosa says they wish it could be longer!). Yet just when we thought we’d got used to Marquez, waiting for Lorenzo’s tire to be cooked so he could dart past for the win, Lorenzo at Valencia comes up with a way to keep Mr. Smiles at bay until the flag. How? Maybe 2016 will tell us. Riders adapt and machines are adapted.

Other forces are at work. Next year Michelin takes over from Bridgestone as spec tire supplier. All the teams acknowledge that 2016 will be an invisible race to develop chassis and riding style to the new tires. When I asked at Valencia what kinds of changes will be needed, I was told to review what was done back in 2008 to make Bridgestones work, then reverse it!

The first visible sign of réadaptation was front and rear wheels moved forward to their adjustment limits, shifting engine weight to the rear. At Laguna 2008, Rossi had needed to brake 45 feet earlier for the top of the Corkscrew on Bridgestones than with Michelins. Nothing seemed to work. Then Rossi’s engineer Jeremy Burgess counterintuitively raised the bike and the 45 feet disappeared. A higher CG more forcefully transferred weight forward during braking, speeding up the growth of front grip by working and heating the tire. This became the center of making Bridgestones work—to actively drive heat into them.

Riders in 2015’s Michelin tests have praised the rear as “super-grippy” but have reservations about the front, which at present limits corner entry and exit. In tests, those least affected by the switch have in general been riders already experienced with the special Open Class soft Bridgestone rear—most notably Maverick Viñales, who was second in the last Michelin test.

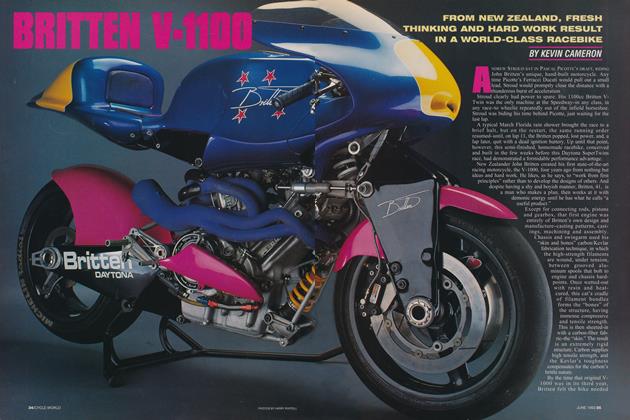

2015 CHAMPION: Will Michelin’s return help or hinder Yamaha’s corner-speed advantage? Too early to tell.

Engines, once so central to Grand Prix performance (the 500s doubled in power in the 20 years after 1975), are also divided in nature. The rider needs power, but to get more of it, the engine’s rpm range of power delivery must be sacrificed; top speed and rideability are opposed. This too has divided Honda and YamahaHonda going for power, Yamaha a few mph slower, going for a wider power range. It was to bridge this divide that electronics first came into being. The primary tool has been the virtual powerband, implemented through the nowfamiliar throttle-by-wire system. As an engine is made more powerful, its torque curve develops hard-to-ride features—peaks, valleys, and regions of steep increase that a human throttle hand cannot traverse.

Virtual powerband fills in the valleys by opening the throttle and trims the peaks by closing it, just as the fast-moving “tail feathers” of an F/A-18 keep it smoothly on the glide path to the carrier. The rider perceives not peaks and valleys but a smoothed torque curve. There are limits to how rough an engine can be acceptably smoothed, and Honda may have committed a strategic error by exceeding them in 2015.

Since 1993, the steady march of chassis to ever higher stiffness has halted, and recent seasons in MotoGP have seen Yamaha and Honda testing one after another chassis or swingarm in hope that the correct flexure of those parts at maximum lean (which has reached 64 degrees from the vertical!) can absorb pavement roughness to keep tires hooked up (see “Feeling the Edge,” November 2015). With a more rigid chassis, tires skip from bump crest to bump crest, with zero grip between.

Yet as all in the paddock know, the wrong kind of chassis flexure can lead straight to either chatter or outright instability. If you carefully follow what the riders are saying, you know chatter is still with us. As so often in life, solutions to known problems discover or create new problems.

When asked, “What in MotoGP do you find most unusual?” Marquez answered, “The front Bridgestone tire. You can just keep loading it.”

The more you work it, the hotter it gets, and the better it grips—making possible the severe brake problems encountered by Ben Spies at Motegi in 2012; front grip enabled him to brake hard enough to push his discs into 1,000-degree Celsius heat failure in three laps. Riders are now allowed the option of heavier, wheel-filling 340mm discs, but we surely have not seen the end of this.

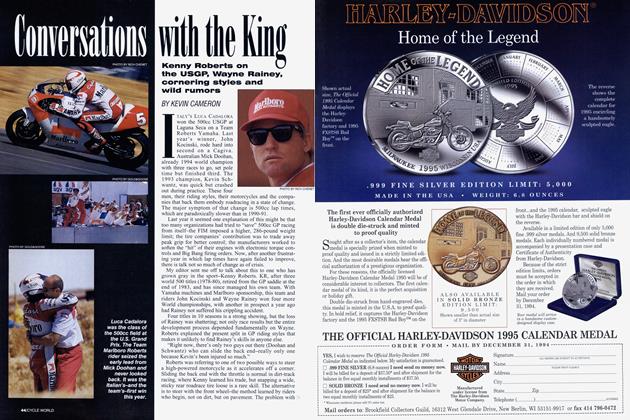

MARQUEZ REBOUND? Following 13 wins in 2014, the Spanish star fell six times last season.

Budgets are annual, but technical rules are subject to change at any time. That means a team may have to redirect their “R&D hose” on to new areas when other areas are denied. Top teams will get six engines per rider in 2016, with an in-season development freeze. That de-emphasizes expensive engine development, so where do the liberated R&D dollars then go? This season we’ve seen the top teams pull away even farther from their satellites. When riders like Marquez or Casey Stoner have said they’ve used almost no traction control in certain corners, listeners think they’ve turned off the electronics. Think again: When the garbled complex three-axis signals from on-board Inertial Measuring Units (IMUs) are subjected to Fourier and other analyses, previously unsuspected chassis motions have been discovered and ways to stabilize them devised. The result may be more stable and faster corner entry. This is science in service to vehicle dynamics. In the Bell X-i, pilot Chuck Yeager had to fly weeks of stability tests at precise speed increments to map the growth of that aircraft’s instability as it approached the speed of sound, but an IMU would have seen it immediately.

Will next year’s “common software” and spec ECU put an end to such science? This is yet another of MotoGP’s point/counterpoints. The business side wants lower-cost “bowling-ball bikes” so that more teams and sponsors may join the series and compete. The factories value racing as an essential R&D activity. Neither side feels the other’s motivations, so the situation oscillates between favoring the rules-makers or the teams. When engines became a denied area, flexible chassis development increased rapidly. When spec ECUs were required, interest shifted to IMU data, enabling rapid progress in stable corner entry. Riders already wear sophisticated crashdetection electronics in their “inflatable Batman suits.” What other electronics might they carry in the future?

Racing has given itself a public-relations black eye through the accusations and counter-accusations resulting from the Rossi-Marquez encounters at Phillip Island and Sepang, culminating in contact between their bikes, Marquez’s fall, and Rossi’s penalty start from last position at Valencia, still leading the championship by seven points. By beating the two Hondas and winning Valencia with Rossi lost in fourth place, Lorenzo became champion.

More than enough has been said, both by the riders and by nearly everyone else, and the quality of the “debate” has been embarrassingly poor. Because of the godlike skills of MotoGP’s top riders, we unconsciously expect excellence in all things from them and are disappointed when they reveal “feet of clay” like our own. You can be sure that tedious emergency meetings have been held and wordy contract penalty clauses added, the gist of which is, “Least said, soonest mended.” As stated above, only the eternal rivals Yamaha and Honda have won since Phillip Island 2010. Does Dorna, the business side, truly base rules on cutting costs so more teams will join, increasing competition? Those goals were ill served by leaving Ducati out so long. Honda resents Ducati’s two successful years, 2003 and 2007, calling them “pirates,” and threatened to leave the series if common software or a rev limit were imposed. Common software is here, but Honda remains. What bargain brought this result? If “more teams equal more competition,” was legal action the best play to keep Kawasaki in the series after 2009? The politics are unseen, so we look for their effects.

There will be racing.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontOh, Character

March 2016 By Mark Hoyer -

Intake

IntakeIntake

March 2016 -

Ignition

IgnitionThe Plight of the Modern Piston

March 2016 By Kevin Cameron -

Ride Smart

Ride SmartMentoring Tips Mother Goose And You

March 2016 By John L. Stein -

Ignition

IgnitionWho the Hell Is Peter Egan?

March 2016 By Peter Jones -

Ignition

IgnitionA Future For Air Cooling?

March 2016 By Kevin Cameron