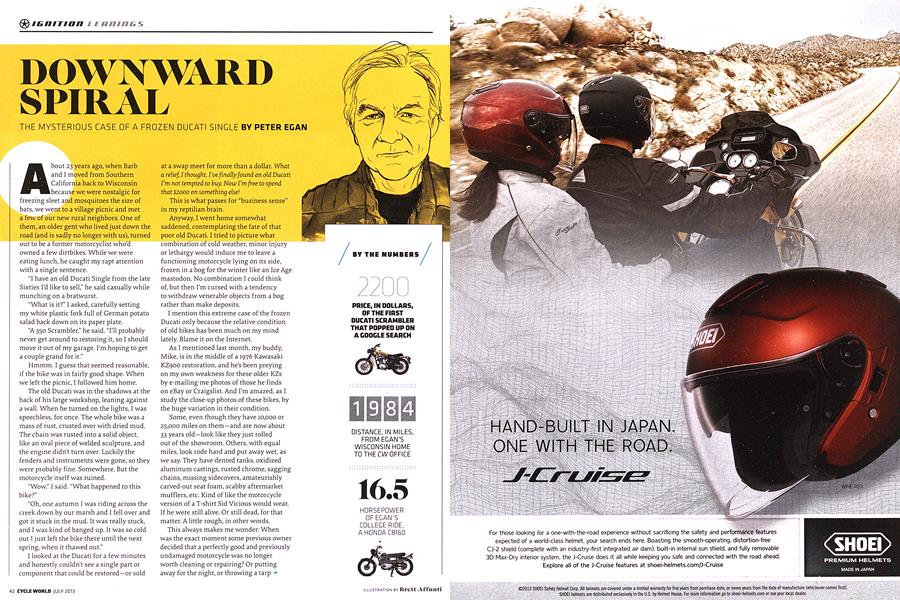

DOWNWARD SPIRAL

IGNITION

LEANINGS

THE MYSTERIOUS CASE OF A FROZEN DUCATI SINGLE

PETER EGAN

About 23 years ago, when Barb and I moved from Southern California back to Wisconsin because we were nostalgic for freezing sleet and mosquitoes the size of bats, we went to a village picnic and met a few of our new rural neighbors. One of them, an older gent who lived just down the road (and is sadly no longer with us), turned out to be a former motorcyclist who’d owned a few dirtbikes. While we were eating lunch, he caught my rapt attention with a single sentence.

“I have an old Ducati Single from the late Sixties I’d like to sell,” he said casually while munching on a bratwurst.

"What is it?” I asked, carefully setting my white plastic fork full of German potato salad back down on its paper plate.

"A 350 Scrambler,” he said. “I’ll probably never get around to restoring it, so I should move it out of my garage. I’m hoping to get a couple grand for it.”

Hmmm. I guess that seemed reasonable, if the bike was in fairly good shape. When we left the picnic, I followed him home.

The old Ducati was in the shadows at the back of his large workshop, leaning against a wall. When he turned on the lights, I was speechless, for once. The whole bike was a mass of rust, crusted over with dried mud. The chain was rusted into a solid object, like an oval piece of welded sculpture, and the engine didn’t turn over. Luckily the fenders and instruments were gone, so they were probably fine. Somewhere. But the motorcycle itself was ruined.

“Wow,” I said. “What happened to this bike?”

“Oh, one autumn I was riding across the creek down by our marsh and I fell over and got it stuck in the mud. It was really stuck, and I was kind of banged up. It was so cold out I just left the bike there until the next spring, when it thawed out.”

I looked at the Ducati for a few minutes and honestly couldn’t see a single part or component that could be restored—or sold

at a swap meet for more than a dollar. What a relief, I thought. I’ve finally found an old Ducati I'm not tempted to buy. Now I’m free to spend that $2000 on something else!

This is what passes for “business sense” in my reptilian brain.

Anyway, I went home somewhat saddened, contemplating the fate of that poor old Ducati. I tried to picture what combination of cold weather, minor injury or lethargy would induce me to leave a functioning motorcycle lying on its side, frozen in a bog for the winter like an Ice Age mastodon. No combination I could think of, but then I’m cursed with a tendency to withdraw venerable objects from a bog rather than make deposits.

I mention this extreme case of the frozen Ducati only because the relative condition of old bikes has been much on my mind lately. Blame it on the Internet.

As I mentioned last month, my buddy, Mike, is in the middle of a 1976 Kawasaki KZ900 restoration, and he’s been preying on my own weakness for these older KZs by e-mailing me photos of those he finds on eBay or Craigslist. And I’m amazed, as I study the close-up photos of these bikes, by the huge variation in their condition.

Some, even though they have 10,000 or 25,000 miles on them—and are now about 33 years old —look like they just rolled out of the showroom. Others, with equal miles, look rode hard and put away wet, as we say. They have dented tanks, oxidized aluminum castings, rusted chrome, sagging chains, missing sidecovers, amateurishly carved-out seat foam, scabby aftermarket mufflers, etc. Kind of like the motorcycle version of a T-shirt Sid Vicious would wear. If he were still alive. Or still dead, for that matter. A little rough, in other words.

This always makes me wonder: When was the exact moment some previous owner decided that a perfectly good and previously undamaged motorcycle was no longer worth cleaning or repairing? Or putting away for the night, or throwing a tarp ->

BY THE NUMBERS

2200 PRICE, IN DOLLARS, OF THE FIRST DUCATI SCRAMBLER THAT POPPED UP ON A GOOGLE SEARCH

EI~~ DISTANCE, IN MILES, FROM EGAN'S WISCONSIN HOME TO THE CW OFFICE

16.5 HORSEPOWER OF EGAN'S COLLEGE RIDE, A HONDA CBlbO

over in a snowstorm. At what point in a bike’s life is it no longer worth it to replace a damaged speedometer or a lost sidecover? Where’s the tipping point?

Obviously, economics figure into this. We’ve all had hard times when “funs are running low,” as John Lennon used to say, and we just can’t afford to fix something right away.

Or any time in the foreseeable future. Which is why I used to commute to school in the snow on a Honda CB160 with a bald rear tire and a dead battery.

And then there’s the “I gave this bike to my little brother while I was in Afghanistan” factor, which can cause serious setbacks in cosmetic excellence. Luckily my little brother was only 8 while I was in the Army, but I had my parents sell that CB160 anyway, just to be safe. Statistics show that 80 percent of all damage is caused by younger brothers.

And then there’s creeping decay. When a bike gets to be 10 or 12 years

old and goes through a couple of owners, it can get incrementally frayed around the edges until the next dent or oil leak doesn’t seem all that critical, usually because the bike is toward the bottom of its downward value curve.

Our former CW Editor, Allan Girdler, always maintained that it took at least 20 years for a basically good design to come back around and be appreciated again after a period of public indifference. And I’d say that’s still pretty accurate—stretching, perhaps, to 30 years, in some cases. Seems we have a cultural tendency to forget good stuff and then suddenly remember it.

So I guess the trick we face as motorcycle owners is to nurse them through that slump in order to create the next generation of survivors, and to remind ourselves that honest utility will generally outlast the whims of fashion. Compared with so many other things (a house, for instance), a motorcycle seems like

such a simple object to preserve.

It’s so easy to store, cover, wipe down and just save from casual damage that there’s no one factorshort of crashing—that should turn it into junk. Other than sheer laziness.

And no one is lazier than I am, or so my mother used say. That’s why these Kawasaki e-mails from Mike are good for me. I carefully examine the ruins of what was once a nice new 1980 Zi-R, and it automatically makes my hair stand on end. I’m then inspired to get out of my chair, go out to the garage and wipe down my most recently ridden bike with a soft cloth, clean the rims, get the bugs off the fork tubes, etc.

A lot of things can go wrong in the life of a motorcycle, but it looks to me as if the downward spiral generally starts with nothing more exotic than a mixture of moisture and dirt. They’re the foot in the door that leads straight to the frozen bog. TUB

AT WHAT POINT IN A BIKE’S LIFE IS IT NO LONGER WORTH IT TO REPLACE A DAMAGED SPEEDOMETER OR A LOST SIDECOVER? WHERE’S THE TIPPING POINT?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontFor the Love of Bikes

July 2013 By Mark Hoyer -

Intake

IntakeIntake

July 2013 -

Ignition

Ignition2013 Ducati Hypermotard

July 2013 By Blake Conner -

Bye Bye 2v?

July 2013 -

Ignition

Ignition2013 Harley-Davidson Iron 883 Sportster

July 2013 By Jamie Elvidge -

Ignition

IgnitionEthanol: What's the Fuss? Fuel For Thought

July 2013 By Kevin Cameron