Return of a Cult Classic

LEANINGS

PETER EGAN

WHEN I WAS IN HIGH SCHOOL IN THE mid-Sixties, dazzling my way to a perfectly mediocre scholastic record, my parents used to drive 70 miles down to the University of Wisconsin in Madison to visit my smarter older sister, Barbara, who was a student there. Whenever possible, I would bum a ride and go with them.

I hate to admit it, but the main reason I came along (not that I didn’t like my sister) was to visit motorcycle shops. Particularly a Triumph—and other brands—dealership called Cycles Incorporated, on University Avenue. I’d have my folks drop me off there, promising to join everyone later for dinner.

My usual routine was to lurk around Cycles Incorporated drooling over all the bikes I couldn’t afford, then hike down to the Student Union to visit the Rathskeller, a big Germanic-style beer hall where all the beatniks hung out.

There, I would buy The New York Times, get a cup of coffee, light a cigarette and try to blend in, peering over the top of my paper to see how real beatniks behaved. I’m sure they thought I was one of them.

Of course, an apprentice beatnik can’t read The New York Times forever, so I’d also kill time reading all the motorcycle brochures I’d snagged.

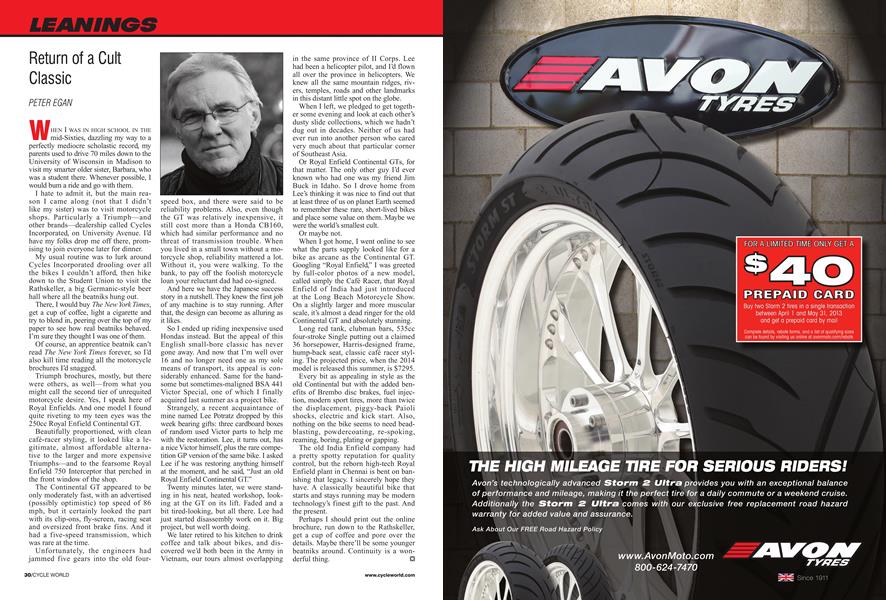

Triumph brochures, mostly, but there were others, as well—from what you might call the second tier of unrequited motorcycle desire. Yes, I speak here of Royal Enfields. And one model I found quite riveting to my teen eyes was the 250cc Royal Enfield Continental GT.

Beautifully proportioned, with clean café-racer styling, it looked like a legitimate, almost affordable alternative to the larger and more expensive Triumphs—and to the fearsome Royal Enfield 750 Interceptor that perched in the front window of the shop.

The Continental GT appeared to be only moderately fast, with an advertised (possibly optimistic) top speed of 86 mph, but it certainly looked the part with its clip-ons, fly-screen, racing seat and oversized front brake fins. And it had a five-speed transmission, which was rare at the time.

Unfortunately, the engineers had jammed five gears into the old fourspeed box, and there were said to be reliability problems. Also, even though the GT was relatively inexpensive, it still cost more than a Honda CB160, which had similar performance and no threat of transmission trouble. When you lived in a small town without a motorcycle shop, reliability mattered a lot. Without it, you were walking. To the bank, to pay off the foolish motorcycle loan your reluctant dad had co-signed.

And here we have the Japanese success story in a nutshell. They knew the first job of any machine is to stay running. After that, the design can become as alluring as it likes.

So I ended up riding inexpensive used Hondas instead. But the appeal of this English small-bore classic has never gone away. And now that I’m well over 16 and no longer need one as my sole means of transport, its appeal is considerably enhanced. Same for the handsome but sometimes-maligned BSA 441 Victor Special, one of which 1 finally acquired last summer as a project bike.

Strangely, a recent acquaintance of mine named Lee Potratz dropped by this week bearing gifts: three cardboard boxes of random used Victor parts to help me with the restoration. Lee, it turns out, has a nice Victor himself, plus the rare competition GP version of the same bike. I asked Lee if he was restoring anything himself at the moment, and he said, “Just an old Royal Enfield Continental GT.”

Twenty minutes later, we were standing in his neat, heated workshop, looking at the GT on its lift. Faded and a bit tired-looking, but all there. Lee had just started disassembly work on it. Big project, but well worth doing.

We later retired to his kitchen to drink coffee and talk about bikes, and discovered we’d both been in the Army in Vietnam, our tours almost overlapping in the same province of II Corps. Lee had been a helicopter pilot, and I’d flown all over the province in helicopters. We knew all the same mountain ridges, rivers, temples, roads and other landmarks in this distant little spot on the globe.

When 1 left, we pledged to get together some evening and look at each other’s dusty slide collections, which we hadn’t dug out in decades. Neither of us had ever run into another person who cared very much about that particular corner of Southeast Asia.

Or Royal Enfield Continental GTs, for that matter. The only other guy I’d ever known who had one was my friend Jim Buck in Idaho. So I drove home from Lee’s thinking it was nice to find out that at least three of us on planet Earth seemed to remember these rare, short-lived bikes and place some value on them. Maybe we were the world’s smallest cult.

Or maybe not.

When 1 got home, I went online to see what the parts supply looked like for a bike as arcane as the Continental GT. Googling “Royal Enfield,” I was greeted by full-color photos of a new model, called simply the Café Racer, that Royal Enfield of India had just introduced at the Long Beach Motorcycle Show. On a slightly larger and more muscular scale, it’s almost a dead ringer for the old Continental GT and absolutely stunning.

Long red tank, clubman bars, 535cc four-stroke Single putting out a claimed 36 horsepower, Harris-designed frame, hump-back seat, classic café racer styling. The projected price, when the 2014 model is released this summer, is $7295.

Every bit as appealing in style as the old Continental but with the added benefits of Brembo disc brakes, fuel injection, modern sport tires, more than twice the displacement, piggy-back Paioli shocks, electric and kick start. Also, nothing on the bike seems to need beadblasting, powdercoating, re-spoking, reaming, boring, plating or gapping.

The old India Enfield company had a pretty spotty reputation for quality control, but the reborn high-tech Royal Enfield plant in Chennai is bent on banishing that legacy. I sincerely hope they have. A classically beautiful bike that starts and stays running may be modern technology’s finest gift to the past. And the present.

Perhaps I should print out the online brochure, run down to the Rathskeller, get a cup of coffee and pore over the details. Maybe there’ll be some younger beatniks around. Continuity is a wonderful thing.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue