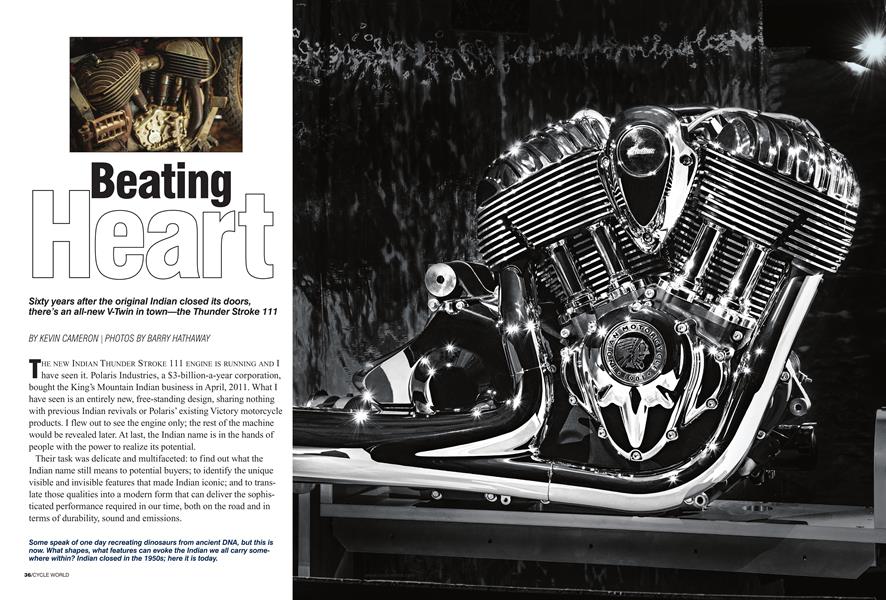

Beating Heart

Sixty years after the original Indian closed its doors, there's an all-new V-Twin in town-the Thunder Stroke 111

KEVIN CAMERON

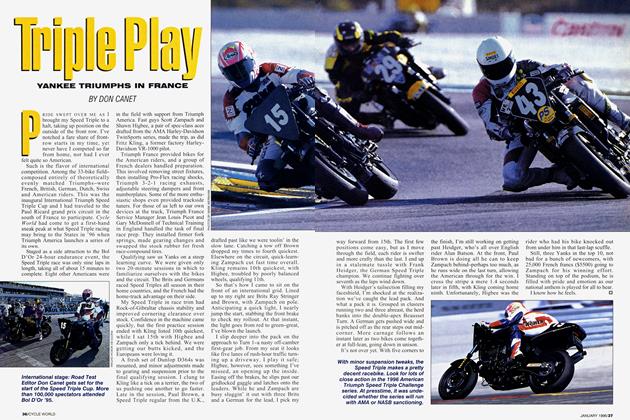

THE NEW INDIAN THUNDER STROKE 111 ENGINE IS RUNNING AND I have seen it. Polaris Industries, a $3-billion-a-year corporation, bought the King's Mountain Indian business in April, 2011. What I have seen is an entirely new, free-standing design, sharing nothing with previous Indian revivals or Polaris' existing Victory motorcycle products. I flew out to see the engine only; the rest of the machine would be revealed later. At last, the Indian name is in the hands of people with the power to realize its potential.

Their task was delicate and multifaceted: to find out what the Indian name still means to potential buyers; to identify the unique visible and invisible features that made Indian iconic; and to trans late those qualities into a modern form that can deliver the sophis ticated performance required in our time, both on the road and in terms of durability, sound and emissions.

The new engine is an air-cooled, 49-degree V-Twin displacing 111 cubic inches from a 101mm bore and a 113mm stroke. Designing this 181 lee engine was made doubly difficult by the need to combine modern technology with the special Indian features that somehow live in the minds of American motorcyclists. Everyone has an “Indian story”—a family member who owned a Chief, who rode the Lincoln Highway to California on an Indian before the war, of someone who raced an Indian in hillclimbs. Call this a “folk memory” if you will, but it has power and value. We’ve seen the process in the creation and success of the “New Beetle” and the “new” Mini automobiles.

Greg Brew is the chief of Polaris ID, its large, respected, and fast-expanding Industrial Design department. Every product it makes passes across his desk. He began by producing a study of Indian from the beginning, and listed their images and features in pages of computer files. He could see that the post-WWI “Powerplus” was too far in the past, and in time, his focus became the 1940 Chief. Although you would list creamy paints, the teardrop gas tank and valanced “Art Deco” fenders, it turned out that what people most remembered as specifically identifying Indian was its engine. Five different renderings incorporating combinations of these features were considered, and the final choice has some salient features: outward-angled cooling fins on the heads (used even on Indian Singles); the contrast of large-diameter heads on the smaller-finned cylinders; downward-angled exhaust pipes; and prominent, largediameter, parallel pushrod tubes. Parallel, not crossed.

How does a major corporation decide to commit serious money to a folk memory? Indian is seen as the only brand iconic and powerful enough to challenge Harley-Davidson for the hearts and minds of American riders. This is classic American enterprise— nothing ventured, nothing gained.

The engine had to have overhead valves for reasons of power, durability, and emissions, yet it has to be recognizably “Indian” in identity. I was particularly curious to see the heads. As the large displacement requires, they are heavily finned. As the need to keep combustion heat out of the heads requires, their exhaust ports are very short. The turn downward to achieve the look is made in bolted-on investment-cast stainless steel elbows, and the turn they make is no more severe than is seen in the headers of four-cylinder sportbikes. Seen from the right, there are the two exhaust headers, pointed straight down.

Each head has just two valves, and their stems are parallel. Each intake port approaches its intake valve on a tangent, causing vigorous charge swirl in the cylinder that generates combustionaccelerating turbulence. Fast combustion is efficient, losing minimum heat. The two valves are slightly tilted as in classic American V-Eight “wedge” combustion chambers. This design is said to be inspired by that of the Corvette LS7 engine. Because of the long stroke, the combustion chamber has the openness to retain turbulence throughout combustion. There is a small squish shelf on the pushrod side.

Separate cylinder construction is employed, and cylinder bores are hard-plated with a Nikasil-like coating. This durable thin plating eliminates the insulating effect and weight of a traditional iron liner. The result is a cooler-running engine, which means better piston durability.

When you make power, you make heat. Ten fins on each head and cylinder cool those parts well, but an overheated piston crown can still heat the fresh charge, forcing use of a lower compression ratio to avoid detonation. Best, therefore, to follow modern practice, with a low-friction, light “ashtray” piston cooled by oil jets, just as were the pistons that powered Lockheed’s Constellation airliner. Two thin, low-drag gas rings are backed by the three-piece oil ring that is best for air-cooled cylinders. These cast pistons are entirely modern—completely flat on top, short-skirted and with short, light wristpins. Powertrain design supervisor Dave Galsworthy noted that reciprocating weight “cascades” through an engine. A heavier piston and con-rod small-end require larger bearings with more friction. They need heavier crank counterweights and balancer. Testimony to effective cooling is the high 9.5:1 compression ratio, which not only boosts torque directly but also reduces fuel consumption. Yes, sportbikes have higher compression, but they are liquid-cooled. Part of the package here is correctly sized valves. Huge valves may have a gut appeal, but by reducing intake velocity they slow midand bottom-end combustion, sacrificing torque. Premium fuel is specified for this engine, but it is protected by detonation sensors and software. If knock is detected, the system retards ignition timing to suppress it.

The side-by-side plain-bearing conrods (the rear cylinder is offset to the left) have surprisingly slender I-beams of constant cross-section. Why so slender? That’s the wrong question. The right question is, why are the rods of older designs so ponderous? The small ends of the rods are tapered, further cutting weight. The insights of Finite Element Analysis are at work here, allowing con-rods to safely shed bearinghammering weight. Rod bigends are manufactured in one piece, then fractured in modern style, allowing perfect registration when the caps are bolted in place—better than dowels, better than the most precise of machined serrations. Remember that serious engines everywhere—from Formula 1 to heavy-duty truck diesels—spin in long-lived, three-layer plain rod and main bearings like these.

Because the rods can be assembled over the single 52mm crankpin, the massive crankshaft can be a rugged one-piece steel forging. When I asked noise, vibration and harshness supervisor (and musician) Anthony Komarek about this crank’s vibratory modes, he replied, “They are all above its operating speed.” Main journals of 62 and 65mm diameter also ride in plain bearings. A

transverse oil gallery at roughly the 4 o’clock position ahead of the crank supplies the grooved main bearings, from which oil enters diagonal drillings in the crank that carry oil to the crankpin and big-ends. There is a single enginespeed balancer, designed to soften but not eliminate engine primary vibration. Engineering can deliver perfect smoothness but riders want to be in touch with what’s happening.

Parallel pushrod tubes require the three cams this engine in fact has. The center cam, with two lobes, drives the intake valves, while single-lobed cams on either side drive the exhausts. The three are connected by helical gears. A single silent chain connects the crank to the center cam. Hydraulic roller tappets drive pushrods and rockers. The 51.3mm intake and 42mm exhaust valves are returned to their seats by single helical springs of tapered “beehive” design. Beehive springs resist spring “surge,” the occurrence of standing waves in the coils. Valve lift is approximately 12mm.

A “Y” manifold connects to each of the engine’s two inlet ports by flexible rubber manifolds, and the throttle-body diameter is 54mm (2 Vs inch). The fuel injectors mount to the “Y,” so their clicking is not radiated from the fin structure of the head. This is a throttle-by-wire engine, controlled by a Bosch ME 17 ECU. Crank angle is reported by a sensor reading the rotation of a large toothed wheel attached to the left crank cheek. Ignition coils for the two plugs—one per cylinderare rubber-mounted to the right of the “Y” intake manifold.

Just as pioneered by Indian long ago, the Thunder Stroke 111 engine is of rigid unit construction with a gear primary drive to the six-speed transmission. The primary gears I saw were of noise-suppressing scissors construction, but the smoothness of the drive, conferred by the substantial crank, may make this unnecessary. There is a three-lobed cam-and-saddle torsional shock absorber built into the primary pinion on the crank itself, and the very large clutch also carries a spring drive of six helical springs. Driveline smoothness has been a major goal with this powertrain.

Why so large a clutch, filling the prominent case on the left side? The large diameter allows fewer plates to do the job, which translates into less lift to disengage. The result? A very light clutch pull.

How much development? I was told, “a billion-and-a-half engine revolutions, a million road miles and 2000 dyno hours.”

This is a serious program. From August, 2011, when Thunder Stroke’s V-Twin configuration was chosen, all this has been accomplished. It has required a large design staff and the corporate will to make it happen quickly.

The six-speed gearbox employs straight-cut gears only for first; second through sixth are quiet-running helicals. By placing more teeth in simultaneous mesh (the so-called contact ratio), helicals soften the load transfer from tooth-to-tooth and increase capacity. All shifting is by dog ring as the end-thrust generated by helical gears would otherwise press against the shift forks.

Final drive to the rear wheel is by toothed belt on the right side. The permanent-mold crankcase splits vertically. A compact starter motor is located at the front, and centrifugal exhaust-valve lifters in each exhaust cam assure quick achievement of starting momentum. The part of the case behind the gearbox is the engine’s oil tank. The gear-driven oil pump is located below it. There were oil coolers on engines I saw, and that’s fine with me. The mighty piston aircraft engines of WWII couldn’t have done without them.

How much power does this monster make? The official word? “The design intent is a strong and broad torque curve,” providing muscular acceleration any time the rider asks for it. Yes, but how much? My back-of-the-envelope estimate is an easy hundred horses. Plenty of power. Torque is claimed to be “over 115 ft.-lb.” Now listen to the engine’s sound (on www.cycleworId.com), which is uniquely syncopated by its close firing order. A distinctive exhaust sound is part of a machine’s identity.

Indian and Harley were great rivals for decades, generating strong loyalties and strong emotions. Another great American tradition is competition, which improves all capable participants. If the new Indian revives that rivalry, it can only be good for all riders.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue