Good Days

TDC

KEVIN CAMERON

I WAS ORIGINALLY ATTRACTED TO THE motorcycle by its human scale. Two men could easily stand a bike on its back wheel in an elevator and take it up to a college room. Two men could wrestle it up stairs from a lighted basement workshop. Two men could put a bike into a van at the end of a hot day at the track—without a ramp.

Try that with your MG or Healey. For cars, you need hydraulic lifts, garages, jacks, hoists. But one man could pick up a 120-pound Kawasaki H1-R engine, set it into the chassis and get the engine bolts through. Bikes were accessible.

Now? I'm not sure. Laptops are easy, true, and the Old Way of tuning, with boxes of brass jets and tapered needles, lacked versatility. Today you can write software that says things like, "Do X according to Routine Y, except under the following interrupt circumstances, in which case execute these other rou tines." Try that with your 6F5 needle, #70 pilot jet and 3.0 slide cutaway.

I made exhaust pipes for two-stroke racebikes. My favorites were the armsfolded "crossover" pipes I made for late TZ35Os-the goal being to use up length as a way to pull the fat pipe cen ter sections toward the front, away from interference with drive chain and tires. Each pipe had dozens of cut-and-welds, and by hammering each welded sec tion using body-working methods, a smooth curve could be achieved that was quite nice. I hated starting a new set of pipes because that meant I had to make myself a prisoner of finickiness for so many hours. But once the header bends were finished and I was satisfied with their smoothness, a sense of ac complishment set in.

Then came titanium pipes on factory 500s, and that feeling of accomplish ment was swept away. These new pipes were really beautiful, welded in inertgas-filled gloveboxes by specialists, not part-timers like myself When a factory bike goes flopping into the gravel trap, with parts flying off in all directions, 20 minutes later, it emerges from the garage looking perfect. Big boxes up in the truck contain multiple sets of perfec tion-pipes and new carbon bodywork with all decals positioned as spelled out in the sponsorship agreements. Yes, we did dream of such a world back in the 1970s, but our reality was gas-welding cracking steel factory pipes using an oil drum as a work surface.

Nobody fixes anything today: "Fit new" is the phrase, with the imperfect parts going to the crusher. Nobody works on engines. They come in sealed cais sons that cost more than a whole TZ750 did, and rules tell you how many you get. No touching-against the rules!

When our TZ75Os crashed themselves to junk, with their $2000-a-set Toomey pipes crushed flat, there were no spares in the truck. So, the time-honored meth ods were used. With an abrasive disc, the dreaded "death-grinder" flexibleshaft machine was called into play, cut ting the pipe at a weld into two pieces so that each could be tapped, heated and levered back to roundness. Then the two pieces could be rejoined at the cut weld. All better. Mostly. That's how one bike I spent three seasons with came to earn the description, "Black and scrungy East-Coast bike" from a California colleague. It looked like a 300-hour Mustang in the European Theater, 1945. Dents. Black streaks. But fast.

In the 1960s, ignition timing was fixed except for the scatter caused by crankshaft vibration and flexure. You sat cross-legged on the ignition side of your bike, with a dial-gauge adapter screwed into the #1 cylinder's spark plug hole, and worked to get the mag neto's contact breakers (yes, crude mechanical switches, not a Hall-effect device in sight) to stop conducting cur rent just as the piston got to the chosen point-say, 2.0mm BTDC.

In the 1970s, some really shaky elec tronic magnetos appeared, each contain ing about $2 worth of cheesy radio parts and a lot of magnet wire. But they could do something new: retard the timing as your engine's pipes began to pump air. Before, compromise was everything. For Daytona, you might set a 250 at 1.6mm BTDC, and for twisty Loudon, the full 2.0. Then in the 1980s came multiple ignition curves selected by four or six dip-switches on the ignition box. Compromise was on its way out the window. And please pay this amount. Progress ain't cheap.

Today, never mind alternate igni tion curves; riders can now select en tire alternate realities from the array of switches at their left thumb (see, all that texting-while-driving is a valuable life skill after all). Rain I, TI and ITT are just the beginning. I think virtuosos like Marco Melandri can play toccatas and canzonas on theirs as they duel for the lead in World Supers. More and more streetbikes are showing up with similar systems, and people like them because they give confidence.

I still have my Okuda Koki meter, in case an unlikely time reversal brings back points magnetos. The dwell meter, however, did go into the dumpster last time. I don't miss my 1965 TD1-B's MC-2RY magneto, whose coils even tually arced through their linen-andvarnish insulation to the nearby spin ning rotor and left a small black charred "witness mark." Time for a new coil. I don't miss Lucas magnetos, either, with their angular-contact bearings supported on cups of moist paper.

Those were good days, seated fac ing the ignition side of a bike in strong sunlight, but they weren't the good old days. As long as good days keep com ing, there's no need for any "good old days." It's so pleasant to know that, once set, a non-contact magnetic ig nition trigger never goes out of time. Goodbye, contact breakers, coils, con densers and rubbing blocks (don't forget the drop of oil for the bit of felt, held in a metal clamp so it wipes lube onto the points cam).

In sum? There has been wonderful progress in function, but in the process, the motorcycle has become less acces sible. I don't have a glovebox or a shop full of titanium sheet. I don't have CNC with which to make lovely chassis side beams like those I've admired on the Attack Performance CRT bike; I just have my old 1971 manual Bridgeport mill. But its motor still makes that busy, complex "we're getting things done" sound I've always enjoyed. I used it last week-to make a part for the latch mechanism of my screen door.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontCar Connections

February 2013 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

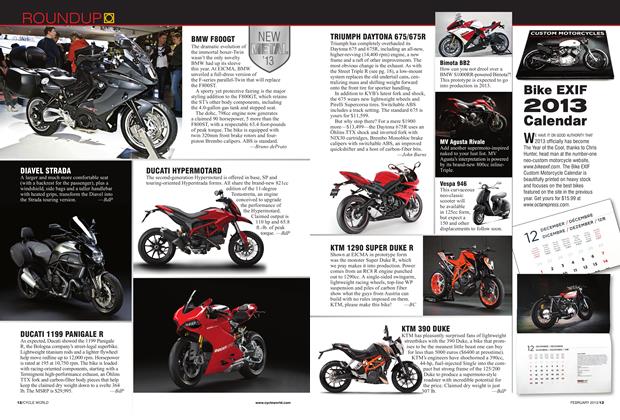

RoundupBike Exif 2013 Calendar

February 2013 -

Roundup

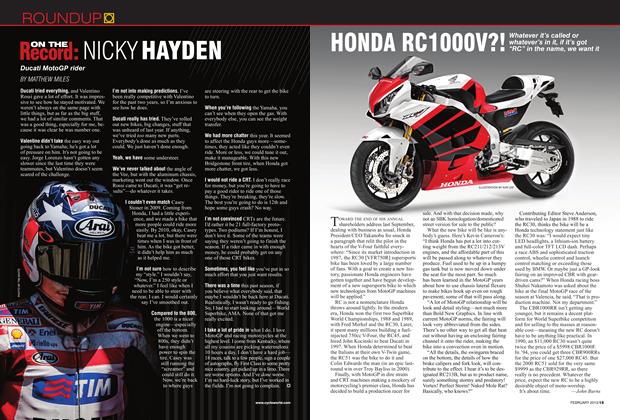

RoundupOn the Record: Nicky Hayden

February 2013 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

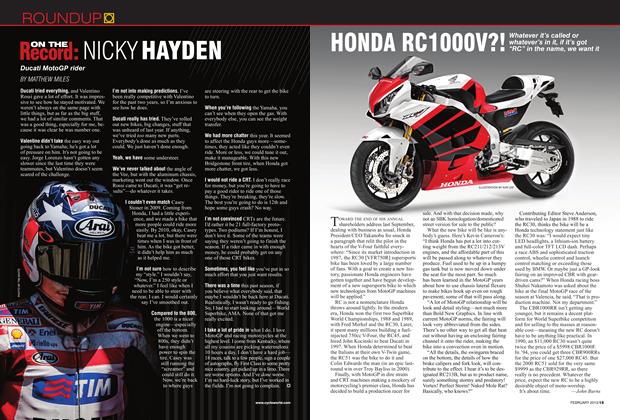

RoundupHonda Rc1000v?!

February 2013 By John Burns -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago February 1988

February 2013 By John Burns -

Roundup

RoundupÖhlins Mechatronic Shock

February 2013 By Don Canet