EL Solitario

The new Europeans: custom motorcycles, friends, clothes, life

GARY INMAN

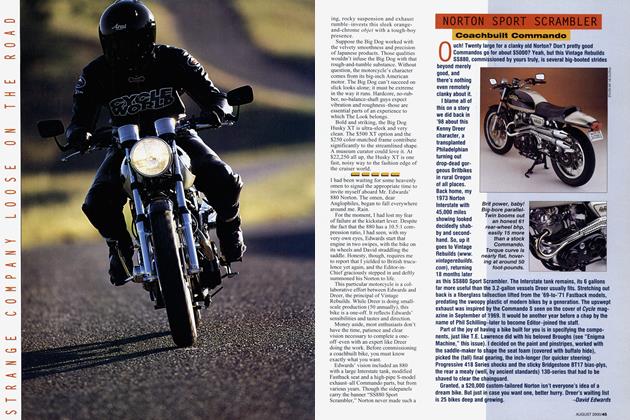

THE DOUBLE GARAGE DOORS RISE TO REVEAL A COLLECTION OF FRANKENSTEINesque specials. They have very little in common with each other. There is no theme, either obvious or subliminal, except they were all built by one ambitious and rambunctious outfit, El Solitario MC.

Center stage is a rigid Single with the ergonomics of a 1960s dragster and the power of an early '80s Yamaha 250. There's a BMW Boxer with deranged art skillfully scrawled all over the tank and headlight eyes that make it look like it's been kicked squarely in the nuts that instant. Next to it is a bare-metal café racer Guzzi. Also in the workshop is a classic Ducati 450 racebike and a Panhead with a lot of miles on it.

It's mid-November in Galicia, Spain, a stone's throw from the Atlantic coast and 30 miles from the northern border of Portugal. It has rained here for a week, but today there is barely a cloud in the sky. The extended El Solitario MC family is in attendance. They will let me ride their bikes, and then vocalize their vision.

El Solitario's head honcho, David Borras, is not your average custom bike buildet The gregarious Spaniard is not your average anything. With his partner (life and business), Valeria Libano, they form the core of the company, run from their impressive home, set not far from the middle of nowhere in Spain.

Despite being up `til 5 a.m. talking the day before, Borras is buzzing from one motorcycle to the next, topping up fuel, lifting and shifting. The 35-year-old is a hairy ball of energy, all beard, teeth, ex pensive denim and hearty backslaps. He reminds me of a rogue ambassador sta tioned in a far-flung, tropical ex-colony, crossed with a gremlin.

I've met Borras at various events across Europe. He's rarely anything other than the life and soul of any party that's going on, but this is the most seri ous I've ever seen him. This morning is about motorcycles and reputation. He ricochets from one bike to the next, fin gering fuel taps, switching on ignitions, then swinging on kicker pedals or prod ding electric starter buttons. Something

I didn't expect happens. Every bike starts first try. The collection of aircooled misfits sits, patiently ticking ovet No drama, no excuses. I was ex pecting more temperamental behaviot

I'm pointed to Trimotoro, a 1983 Guzzi 650 with twin Porsche foglights at the front, a Chabott-style tank in the middle and BMW R50 fishtail pipes.

Trimotoro is named after a fantastical machine from a book Borras reads to his two children. "A bear's friends make the machine for him;' he explains. "It runs on imagination. Stop imagining and it starts to sink."

I've had rides like that. But the bare-metal V-Twin doesn't re quire a suspension of belief to get to grips with. It's a well-built café racer, with the kind of ergonomics I expected. Other than the long reach to the Italian Kustom Tech levers, everything is as I'd want it.

We turn right out of El Solitario's walled compound and head into the pine-covered Oia mountains. Borras is riding his own `59 Harley Panhead. It's flat black, covered in oil and road grime.

His right-hand man and friend since their school years, Lazlo, is riding The Winning Loser. It's the dragbike-aping Yamaha SR250 El Solitario bought and built with a budget of 1000 euros to enter a Spanish competition that limited customizers to that expenditure. Valeria, a statuesque and radiant blonde, is riding Gonzo, the shop bike, a BMW 450 boxer that David has owned for nearly 20 years.

As expected, Borras disappears in an explosion of decibels. Lazlo hares after him, eventually catching up. The two have a blazing, Southern European row, complete with two-handed gestures, at 50 mph. Whatever it was about is for gotten by the time we stop.

The roads are damp and unfamiliar. They curve through trees and climb to a flat-topped peak. I fit the Guzzi like a

glove. I haven't ridden one since I sold my own 1000cc café racer a couple of years ago. This 650 is lighter without being significantly slower.

Wild ponies crowd the otherwise de serted road. This is Borras' backyard test road and head-clearer. When he only has an hour to squeeze in a ride, this is where he comes. He's hustling the ancient Harley at an impressive pace, and I'm giving Trimotoro enough of a workout to know it's well-put-together. Borras builds his bikes with the help of a local jack-ofall-trades engineering genius.

Lazlo's butt is 18 inches above the floor. His wrists are lower than his knees. When he's wringing the 250's neck, he adopts a flat-track, foot-out style. From behind, it is equal parts im pressive and terrifying.

"Lazlo is the oniy one who can ride that bike," Borras explains. It looks as comfortable as an ingrown toenail.

We stop at a village cantina. The el derly owner is visibly perturbed as we walk in, not rude as much as confused. Not because we've arrived on bikes, but because this is a Friday, she wasn't expecting anyone except the regulars and the only food she cooked was for herself Still, she sells it to us, plus five bottles of local beer, some Pepsi and coffee. It's so cheap, I check the price three times.

The only other customers are local laborers chowing down in silence. When they're finished, they walk out to the bikes and stare at them, slack-jawed. They're so confounded by the whackedout motos they can't think of a question between them. You don't often see bikes like these in this area of Spain. In fact, you don't very often see a collection like this in many places in the world. When a model-like blonde in tight jeans, Red Wing boots and white-framed sunglasses walks up to the tallest of the bikes, pulls on a green metalfiake open-face and pre pares to ride off, the shaven-headed farm workers are agog.

Borras offers me my first-ever ride on a Panhead. I jump at it. Now come the warnings, one of which is, "The brakes aren't very good." Within a couple of miles, I have huge respect for David as a rider. This thing-his own, never-for sale-bike-is as lethal as anthrax. We make it back to El Solitario HQ.

Valeria's dad, who lives with the family, has prepared black rice and squid. The weather is mild enough to sit outside to eat. The family's live-in housekeeper brings out local beer, crusty bread and homemade garlic mayo. More friends have arrived. Four hounds gambol around the place-only one belongs to the house hold, others have arrived with friends. The scene has nothing to do with bikes but everything to do with El Solitario.

This is, it seems, the pace of El Sol life. Motorcycles are important, but only part of a bigger picture. In that picture are family, friends, road trips, racing, big meals, late nights, expensive liquor and high-end clothing and accessories. The good life. Of the eight people around the table, only three live in the house, yet all eight will still be here, drinking and dancing, at 3 a.m. "We were living in Miami," Borras

explains, "but had to return to Spain to sort out some family issues. When we came back, Valeria and I decided to try to do something nobody does."

That "something" is making riding clothing and accessories at the top end. These aren't pieces to compete with

Dainese. They truly are things they can't find elsewhere, like "selvedge" denim riding Bonneville coveralls. The mate rial is woven in Japan, then shipped to Europe where the suits are made in very limited numbers. They have incredible detail. "They empower me when I wear them. They make me feel invincible," says David, a little dramatically. They cost an unfashionable $498. And yes, they're sell ing, mainly in the U.S., of all places (find yours at www.benchandloom.com). There also are expensive 1930s-style racing sweaters, shoulder bags and much more affordable T-shirts-oh yeah, and alpaca ponchos. Clearly not trying to muscle in on the West Coast Choppers merchandise market, then.

The bikes, those ridden today, plus a Ducati Single called Chupito, the behe moth BMW Baula and a trio of Honda 125s with obnoxious exhaust notes, BMX bars and stunning pop-art paintwork, are at the center of the business but don't form the core. They are essential in building the El Solitario name, or brand, but they are so obtuse, irregular and quirky that they're not going to pay the bills. They attract a lot of interest but not a clamor from buyers.

This is not a surprise for Borras. As he points out, "I've always liked bikes, weird bikes. We want to make money, but I can't do what was done yesterday.

I can't just give people what they want. I wish I could have a theme, like the WrenchMonkees, a selection of parts, the colors, just make dark café rac ers..." He pauses, then realizes, "No, I don't! It would drive me mad."

Despite being far from mainstream, the El Solitario motorcycles are all sold, with the exception of two of the three 125cc Pop bikes (however well-built those ma-

chines might be, 8000 euros is a lot for a 125 in one of the most depressed econo mies in the Western world).

But El Solitario has a plan. "Europeans don't spend their money. Americans do. We want to move back to the East Coast of America. The plan is to have a store, studio, workshop open to the public in three years."

You've had your warning.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

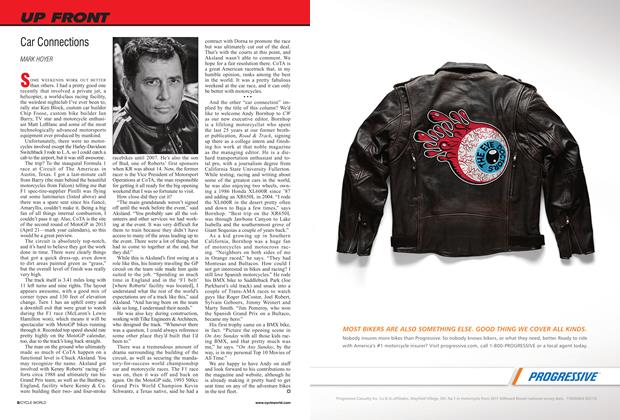

Up FrontCar Connections

February 2013 By Mark Hoyer -

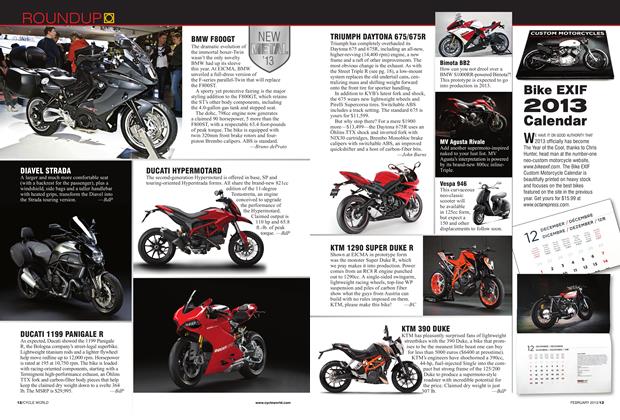

Roundup

RoundupBike Exif 2013 Calendar

February 2013 -

Roundup

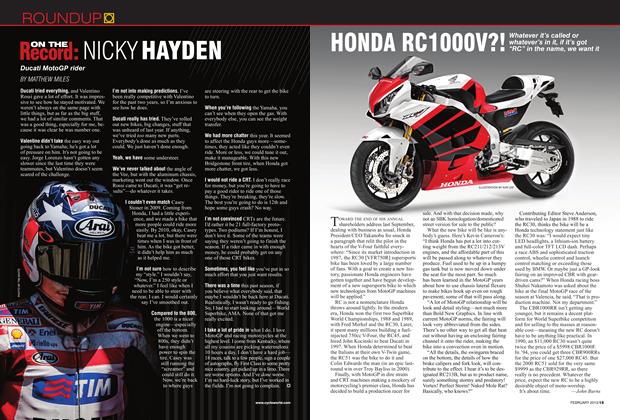

RoundupOn the Record: Nicky Hayden

February 2013 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

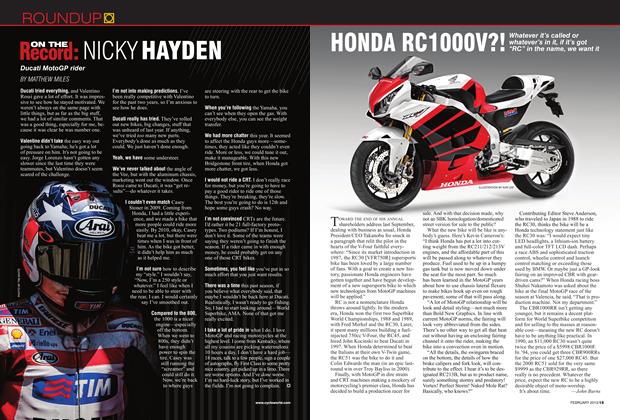

RoundupHonda Rc1000v?!

February 2013 By John Burns -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago February 1988

February 2013 By John Burns -

Roundup

RoundupÖhlins Mechatronic Shock

February 2013 By Don Canet