HOT ON THE CASE

UP FRONT

EDITOR'S LETTER

ONCE MORE WITH FEELING

Is there anything more satisfying than rebuilding your own vintage motorcycle engine and making sure everything is just perfect, from magneto timing to carburetor tune to clutch adjustment to valve timing?

Sure, riding is eminently more satisfying. That’s why people buy new bikes.

They say necessity is the mother of invention, but I say necessity is just a mother. That’s how I got my hands dirty in the first place, plunging into the depths of worn-out carburetors, tapered cylinder bores, shagged rings, loose steering heads and more.

I’m thankful for the mechanical skills I earned when I was 17 trying to make my Yamaha RD400 work as a daily rider. I’d already gone a long way working on my ’71 Triumph TR6 car and was sort of figuring it out, ending up with decent transportation. Lots still to learn, sure, but I had some mechanical aptitude and my dad, a former amateur car drag racer/mechanic and generally handy guy, was there for backup.

I grew to enjoy the challenge, so even when I could afford to pay somebody to work on my stuff, I did most of it myself.

I wanted to see into those dark places and understand what was happening in every corner of the machinery.

My 1954 Velocette MSS 500CC Single is the poster child for this obsession. Velos are magnificent bikes to ride and offer exceptional performance for their era. I bought mine 10 years ago while on vacation in New Zealand, knowing the engine needed a rebuild, due to the pronounced rod knock. Maybe I should have passed. I mean, here was this guy who’d done a full restoration at great expense not that long before, and now he was selling it at what I thought was a pretty good price. All I had to do was have the engine rebuilt.

Which is what I did, getting the work done by a local “specialist.” I left the bike in New Zealand, this guy did the work on it and I later went back to do a touring story, riding my new pride and joy around the South

Island. About halfway through the ride, the engine seized. I should have had a suspicion.

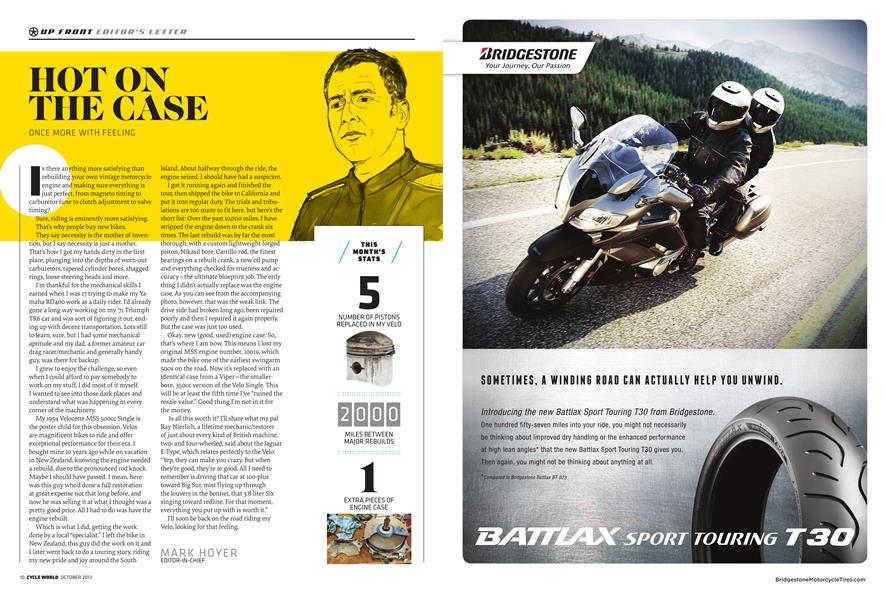

I got it running again and finished the tour, then shipped the bike to California and put it into regular duty. The trials and tribulations are too many to fit here, but here’s the short list: Over the past 10,000 miles, I have stripped the engine down to the crank six times. The last rebuild was by far the most thorough, with a custom lightweight forged piston, Nikasil bore, Carrillo rod, the finest bearings on a rebuilt crank, a new oil pump and everything checked for trueness and accuracy—the ultimate blueprint job. The only thing I didn’t actually replace was the engine case. As you can see from the accompanying photo, however, that was the weak link. The drive side had broken long ago, been repaired poorly and then I repaired it again properly. But the case was just too used.

Okay, new (good, used) engine case. So, that’s where I am now. This means I lost my original MSS engine number, 10019, which made the bike one of the earliest swingarm 500s on the road. Now it’s replaced with an identical case from a Viper—the smallerbore, 350CC version of the Velo Single. This will be at least the fifth time I’ve “ruined the resale value.” Good thing I’m not in it for the money.

Is all this worth it? I’ll share what my pal Ray Nierlich, a lifetime mechanic/restorer of just about every kind of British machine, twoand four-wheeled, said about the Jaguar E-Type, which relates perfectly to the Velo: “Yep, they can make you crazy. But when they’re good, they’re so good. All I need to remember is driving that car at 100-plus toward Big Sur, mist flying up through the louvers in the bonnet, that 3.8-liter Six singing toward redline. For that moment, everything you put up with is worth it.”

I’ll soon be back on the road riding my Velo, looking for that feeling.

MARK HOYER EDITOR-IN-CHIEF

THIS MO NT HS STATS

5 NUMBER OF PISTONS REPLACED IN MYVELO

MILES BETWEEN MAJOR REBUILDS

1 EXTRA PIECES OF ENGINE CASE

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Departments

DepartmentsIntake

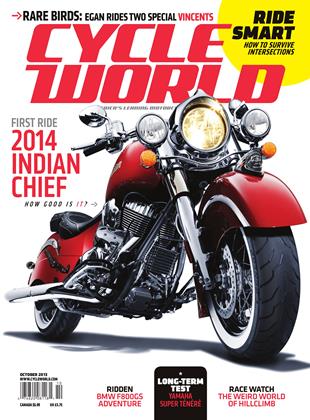

October 2013 -

Ignition

IgnitionCw First Ride 2014 Bmw F800gs Adventure

October 2013 By Blake Conner -

Ignition

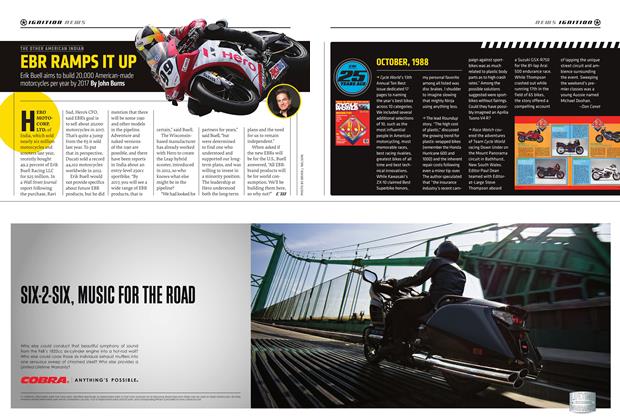

IgnitionThe Other American Indian Ebr Ramps It Up

October 2013 By John Burns -

Ignition

IgnitionCw 25 Years Ago October,1988

October 2013 By Don Canet -

Ignition

IgnitionAmerica's Eicma?

October 2013 -

Ignition

IgnitionOn the Record Carlin Dunne

October 2013 By Andrew Bornhop