HONDA MAN

RACE WATCH

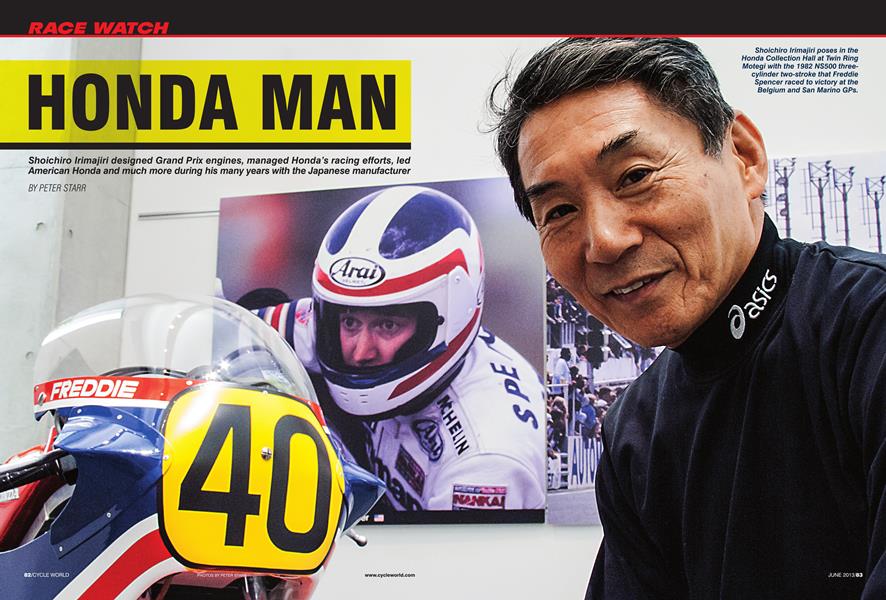

Shoichiro Irimajiri designed Grand Prix engines, managed Honda's racing efforts, led American Honda and much more during his many years with the Japanese manufacturer

PETER STARR

IN THE FALL OF 1985, FREDDIE SPENCER threw a huge party in Shreveport, Louisiana, to celebrate his 250 and 500cc world championships. Among the guests at this grandiose celebration was Shoichiro Irimajiri, president of American Flonda and former head of F1RC. Spencer introduced me to Irimajiri, and we became friends.

Irimajiri is a great engineering talent who rose from a designer’s desk to run one of the world’s most significant companies. His racing successes include penning the 50cc RC115 Twin, 125cc five-cylinder RC147 and most of the RC166—the 250cc Six ridden to backto-back world titles by Mike Hailwood. Irimajiri also designed Honda’s first Formula 1 engine, the 12-cylinder RA271.

Japanese workers rarely become Willie G. Davidson-like icons of the companies for which they work. As such, some talented engineers toil in relative obscurity despite having created designs and inventions that have changed our world. Irimajiri-san is one of those people.

Over the years, I had expressed an interest in riding a motorcycle through rural Japan and experiencing a side of that country most people rarely see. Irimajiri extended an open invitation to me, and we eventually made the ride a reality. The first part took us through typhoon-force rain from Tokyo to Honda's racing facility at Twin Ring Motegi, where our conversation began over a traditional evening meal.

What was your earliest experience with Honda?

When I was at Tokyo University, I learned you could use the intake manifold to increase the inertia of the air to the cylinder and supercharge the cylinder by 20 to 30 percent. Based on this theory, I invented some variable valve timing utilizing hydraulic systems and the variable length of intake pipes— technology that is being used right now.

At that time, Honda had the largest analog computer, and I went to them to prove my calculations. I got a lot of information utilizing that theory and designed a 1.5-liter Formula 1 engine for my graduation project. I was motivated to join Honda’s racing department in 1963, when there were only 10 engineers. My first assignment was to tune up the RC113, because this 50cc engine was the weakest in the class against the Suzuki, Yamaha and Derbi two-strokes. I changed the ignition, intake and valve timing, manifolds and exhaust pipes—everything—and got it to produce 10.8 horsepower at 21,500 rpm. Luigi Taveri won the Japanese GP on the bike that year.

I was then assigned to design the next 50cc racing engine, which eventually became the RC115 that developed 12.8 horsepower at 22,000 or 23,000 rpm. In 1965, that bike won five of seven Grands Prix and the rider and manufacturer championships. I was then asked to design and develop the fivecylinder 125cc engine for the RC149 and the crankshaft, gear train and valve mechanics for the six-cylinder RC166. Mike Hailwood rode the 166 to consecutive world championships in 1966 and 1967.

What was the most important engineering development that Honda made before quitting Grand Prix racing in 1967?

High-speed engines. We changed almost all of the old technologies to rev up our engines.

How was your relationship with Mr Honda in the 1960s?

At that time, Mr. Honda was leading R&D, and every day, he took a walk around the design room. He would stop at the drawing boards of designers and ask, “What are you doing?” When he came to me, I explained this is the crankshaft for the new 250cc Six. He said, “Hmm” and then got angry. “It is too big. This is stupid; too much friction. You can make bearing diameter smaller.” Then, he said, “Do this!”

We knew he would come back later that same day. I had to redesign everything before he returned. It might be four or five hours or the next morning, but I had to recalculate everything. It was a big surprise what he pointed out, but he was always 70-to-80-percent accurate. He had a very good sense for balance; he was a natural engineer.

When did you realize that Freddie Spencer had the potential to be a world champion?

Freddie by Amer ican Honda and the manager of our endurance racing team. The Yoshimura Suzuki team came to the Suzuka 8-Hour in 1980 with Wes Cooley and dominated that race. It was a big shock because we had the RC 1000 and thought it was the fastest. Up to that point, we had only looked at European riders, such as Christian Sarron. We thought there might be other good riders in America, and we found Freddie. The team manager explained Spencer’s potential and asked us to keep him for next year’s 8-Hour. We said that is a good idea to see how fast he is—to see his potential.

At that time, we were in the process of developing the NR500. Freddie wanted to go GP racing, and I told him we would be ready to give him a competitive machine a couple of years later. He said, “No, 1 can’t wait for that.” I asked him what was his desire, and he answered, “I want to be a champion in any kind of racing series—a U.S. title or a world title.”

It was very clear we would need a long time to have a competitive bike for Grand Prix, so we discussed with American Honda about developing special bikes for Freddie: a Superbike and dirt-tracker. Freddie raced our CB750-based Superbike and did some dirt-track races while he waited for a chance to compete for the world championship.

Freddie was so talented and so successful as a young guy that our biggest fear was burnout syndrome. So, when I met Freddie, I told him to make strong private and personal goals for the future.

What is more important, the motorcycle or the rider?

In any kind of sport, there is a ratio between the athlete and his tools. For example, Abebe Bikila won the 1960 Olympic marathon while running barefoot, but more recently, shoes are very important. Therefore, I can say 95 percent people, five percent tool. In golf, the clubs and balls are getting better; without the latest tools, you cannot hit more than 300 yards. So, the human ratio is somewhere around 70 to 30. In motocross, you need the best physical athlete, but at least 50 percent is the machine. In roadracing, I say 60 to 70 percent is the machine and 30 percent is human. But at the same time, there is the combination of the people and machine.

In the 1960s, Honda was too focused on the machine side, especially on the engines. The philosophy was: If we need a good person to ride the bikes, we hire the best available. We did not have a long-term strategy to train one guy to be better; the rider is just the contract person. So, the relationship between machine and rider was not so strong.

When I established HRC, I had a clear vision. One of the objectives was to make the best combination of rider and machine. When I started the NR project and brought in Freddie, we thought we would grow up together—the machine and Spencer. But riders have their own styles. Mike Hailwood was different from Jim Redman. For Redman, our chassis was good enough. He didn’t complain about it. But when Mike rode the bike, he complained a lot. He hated the Honda chassis, and he personally built his own chassis. You will not see a photo of Mike Hailwood in the Honda museum because he did not ride the whole Honda bike.

At that time, we did not understand why Hailwood complained. But in the late 1970s, we could understand: Hailwood slid the wheels, and Redman didn’t. When you slide the wheels, the frame must be very rigid. If it is flexible, you cannot control it. Spencer also had his own unique style. When we set up the machine for Freddie, it was very difficult for another person to ride.

Actually, I could not understand how different Freddie’s style was from others until he told me his secret. When I saw Freddie cornering, his lean angle was so shallow yet much faster than others.

I thought that is not possible—deeper is faster. When I asked Freddie about this, he smiled and said that when he went into a corner, he braked very hard with the front then lifted the rear wheel, twisted his body and turned the bike. He gradually released the brake, opened the throttle and continued to turn the bike. He did not need a deep lean angle.

I asked Freddie, “Are there any other riders in the world who can do that?”

He said, “No, only me.”

Now, I understand why the best bike for Freddie Spencer didn’t fit others.

In the many years that I’ve known Shoichiro Irimajiri, he has always been a leader and often without the recognition he deserved. He continues to be an avid motorcycle enthusiast, and unlike many of his generation, he does not look toward retirement but challenges not yet realized.

Irimajiri-san influenced an entire industry and two generations of motorcyclists, but perhaps no individual more than three-time world champion Freddie Spencer.

“Iri had clarity of purpose,” said Spencer. “He could see the solution and outcome. I understood that feeling of certainty. That was our bond.” □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Features

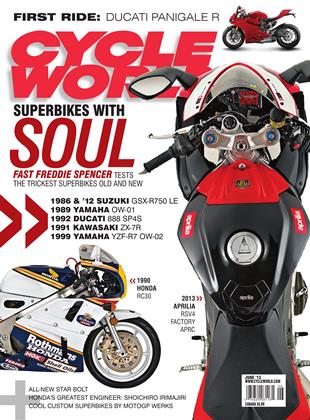

FeaturesSuperbikes With Soul

June 2013 By Freddie Spencer, Nick Ienatsch, Thomas Stevens -

Roundup

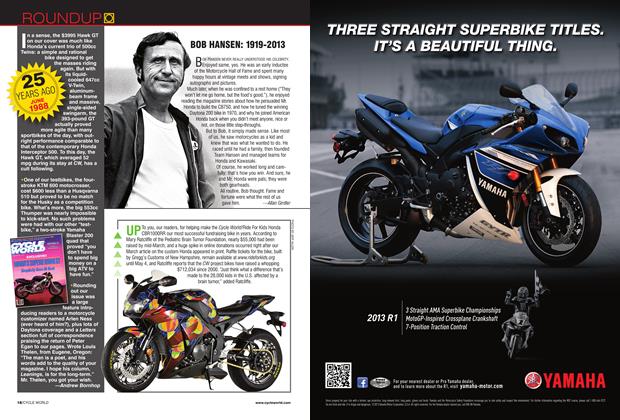

RoundupBob Hansen: 1919-2013

June 2013 By Allan Girdler -

Up Front

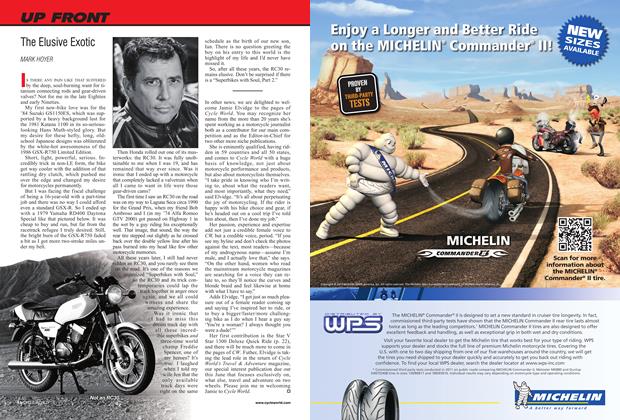

Up FrontThe Elusive Exotic

June 2013 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupOn the Record: Gerbrandtaarts

June 2013 By Matthew Miles -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

June 2013 -

Leanings

LeaningsResurrection of A Superbike

June 2013 By Peter Egan