Know your price

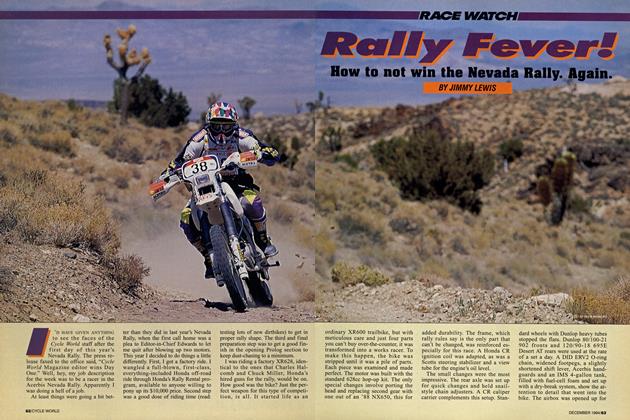

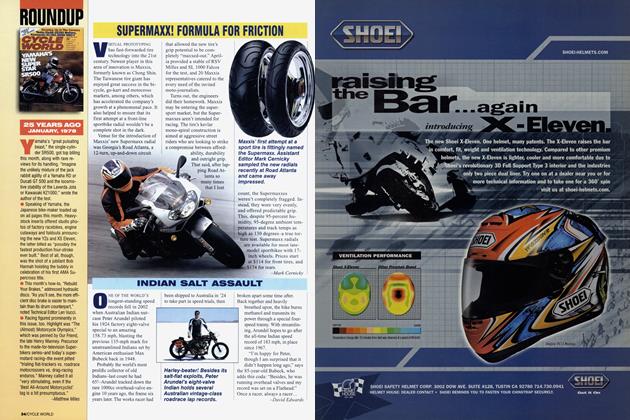

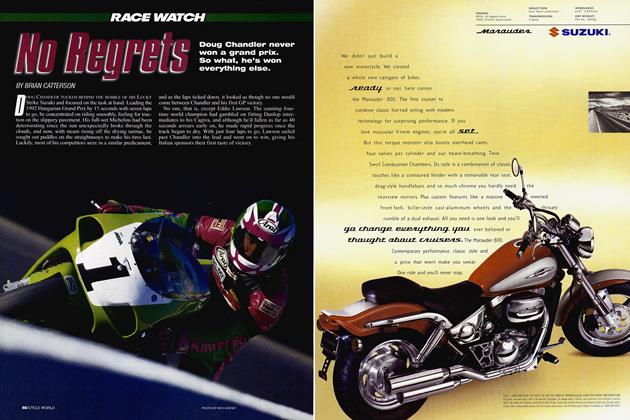

RACE WATCH

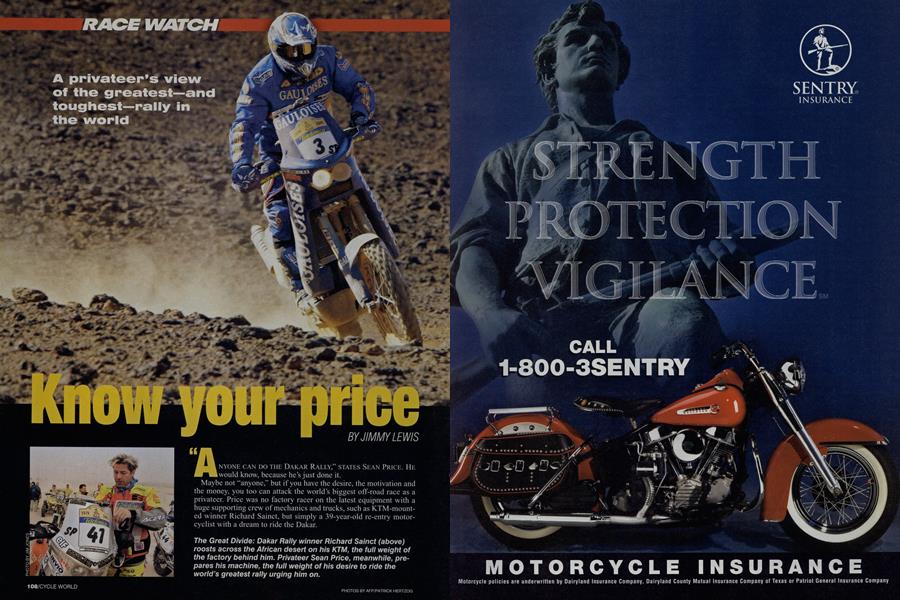

A privateer’s view of the greatest—and toughest—rally in the world

JIMMY LEWIS

ANYONE CAN DO THE DAKAR RALLY,” STATES SEAN PRICE. HE would know, because he’s just done it.

Maybe not “anyone,” but if you have the desire, the motivation and the money, you too can attack the world’s biggest off-road race as a privateer. Price was no factory racer on the latest equipment with a huge supporting crew of mechanics and trucks, such as KTM-mounted winner Richard Sainct, but simply a 39-year-old re-entry motorcyclist with a dream to ride the Dakar.

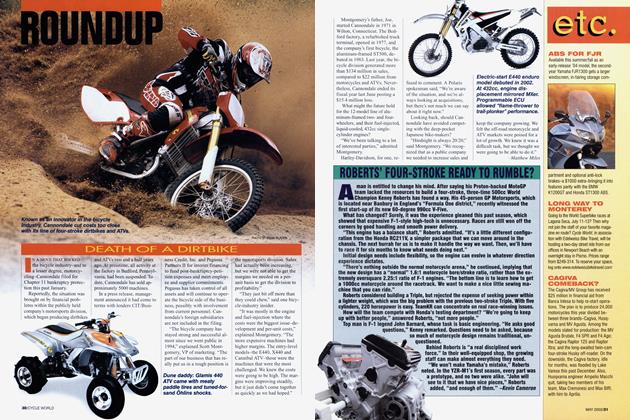

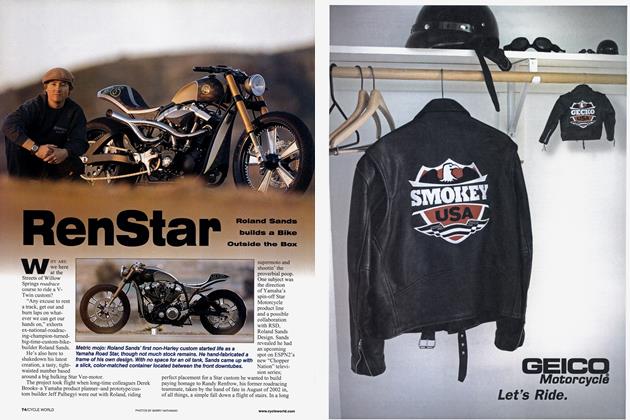

The Great Divide: Dakar Rally winner Richard Sainct (above) roosts across the African desert on his KTM, the full weight of the factory behind him. Privateer Sean Price, meanwhile, prepares his machine, the full weight of his desire to ride the world’s greatest rally urging him on.

since 1 was >out 16, while I was living in Kenya,” Is the Canadian who now resides San Francisco. “Dakar was every/here over there. I started riding on a famaha DTI75 when I was living in ica for four years, then I took a long time away from bikes-until I was 35. Then, I knew what I wanted to do.” Dakar was on the menu. And being successful in the technology business, Price had the means-meaning the money-to do the race right.

The Dakar has a history of welcoming the privateer. That was in the design of the rally from the beginning, as race creator Thierry Sabine originally called the Dakar, “A race for amateurs with room for professionals.”

So Price fit right in. Current race director Hurbert Auriol also touts the second credo that the late Sabine built the race around: “A challenge for those who go, and a dream for those who stay behind.” For Price and many others, myself included, the challenge becomes an addiction. No matter how good or bad your last Dakar went, if you’ve done it once, you’ll want to do it again.

The 25th anniversary edition of the mythical race across Europe and North >

Africa again broke tradition and headed east, away from the usual finishing destination (and namesake) of Dakar, Senegal, in West Africa. This year, the final destination was Sharm El Sheikh in Egypt.

Really, it’s a minor change, because the race is still ruthless, one of the most grueling motorcycle events on the planet. Arguably, you never have a “good” Dakar, only ones that are less painful than others. It is always, for every participant, a life-changing experience, however good or bad. Price was no exception.

I was in a unique position to write this story. For one, I’ve raced Dakar several times, both as a privateer and as a factory team member. And two, I had met Price some time ago, through a Canadian-based logistics service, RallyConnex, that was preparing him for Dakar. They arrange for almost every rally need, from helping to complete the entry form to making sure your spare parts arrive at the end of each stage. They even sent Price to train with me for a few days, to help him get a feel for exactly what he was getting into.

Price had for the last few years taken his riding seriously, hitting the trail frequently with a bunch of ISDE and Baja racers from Northern California. It had obviously paid off, as his riding skills were solid. He had also been training in > the gym and was now seeking navigation, mapbook and desert-survival skills.

Little did he know, though, how realistic it was to have him get up at 3 a.m. to ride 80 miles in the freezing-cold dark as a simulated transfer section.

“It will be something like this, only worse,” I told him. “The Dakar will play with your head in ways that I can’t teach you. You just have to learn as you go and keep your head about you.”

Then I had him do a tough, navigation-intensive 350-mile stage that he struggled with and failed to finish. At the time, I figured he’d make it four or five days in Africa and succumb to the cruel ways of the desert. Unless he really paid attention. Price didn’t have the typical American-style crash-and-burnin-a-ball-of-flames way about him, but I wasn’t so sure about a guy who’d only raced once before doing the biggest rally in the world. Yet he did manage to be > on the winning Sportsman team in the Baja 1000 just a few weeks after our training sessions. Maybe I was underestimating Mr. Price?

In the end, he was about as prepared as you can be for the Dakar. Except for the fact that he didn’t have a bike! New factory-prepped KTM rally replicas need to be ordered almost a year in advance-a deadline he missed-so Price was left with the purchase option of a used KTM Single, fitted with a new motor, which was shipped directly to the start in Marseille, France. At least he had a great mechanic, Christian Webber, lined up. Webber had built motors for KTM in the Austrian company’s race shop, plus he knew his way around the bivouac, a handy skill in the Dakar.

Because Price and Webber didn’t even see the bike until just prior to tech > inspection, they had to work all night before the start of the race to get the orange bomber ready to go. This is a pretty typical scenario for an American rider’s Dakar Experience-I literally had to hunt down my bike in Granada, Spain, for my first rally.

Even with the all-nighter on an unfamiliar bike, Price was confident, going in with one goal: to finish. But the massive scope of the Dakar set in quickly.

“I was looking at it from a North American perspective, where the rally isn’t that popular,” he says. “So the 10,000-plus crowds lining the special stages in Europe were intimidating. This thing is enormous.”

But that big-crowd, race-spectacle vibe changes fast, and the real nature of the Dakar sets in once you reach Northern Africa. Tunisia welcomes the riders with its vast deserts, and these only open > up more once the rally reaches Libya.

“All of a sudden, you are on your own,” recalls Price of his African arrival. “In the first 177-mile stage in Tunisia, I was on a heading where I saw no bikes and no cars for over an hour.” This is one of those things for which you just can’t train, a feeling of loneliness. There’s just you and your machine in the middle of nowhere, yet you’re in the middle of the biggest off-road motorsports event in the world, running in the middle of winter through these old, seemingly dead deserts.

You can’t get a sense of this by watching the rally on television, even though it really is one huge TV production. Car and truck classes add to the storyline, although the bikes still seem to steal the show. Even with the withdrawal of BMW two years ago, thanks to KTM-the only brand still racing at a factory level-the bike com-

petition is as tough as ever. Of course, the Austrian maker absolutely dominates, with machinery that rivals factory bikes of just a few years ago now available to privateers.

KTM has such a stranglehold on the top positions that the factory fields multiple teams so there is some competition. Two-time Dakar winner Richard Sainct led a strong French > contingent backed by cigarette-maker Gauloises. Telefonica Movistar sponsored a Spanish team featuring Nani Roma as its lead rider, while Fabrizio Meoni-winner the last two years-was competing with a ton of Italian sponsors, as was South African Alfie Cox. There are riders from all over the world, and only the U.S. is really missing as a force-blame world political tensions, particularly in the Middle East, as well as difficulties in obtaining travel visas to Libya. There is also the problem of locating sponsors stateside, making it tougher still for Americans to fund a proper assault. Never mind that Speed Channel’s coverage shown in the U.S. this year was the best it’s ever been, timely even.

Once the race really got going, Sainct on his KTM Single did what he prefers: lead from the front. Meoni and Roma were chasing on their V-Twin KTMs, waiting for the faster terrain of the coming Libyan desert, where their more powerful but less maneuverable bikes would shine. Typical of the early stages in Dakar, charging riders took risks and fell off with great regularity as they tried to make the break that would give them an advantage. The carnage makes for exciting racing and, more importantly, good TV.

Price, on the other hand, wasn’t out to make a break. He just wanted to finish. And even this goal he broke down to simply getting to the end of each day. But trouble always comes.

“I knew it would happen and I’d be prepared for it,” says Price of flying off a sharp, wind-cut dune. “Suddenly, I was 15 feet in the air. I gassed it at the last second like I told myself I would. I saved it and landed real hard, but the bike’s frame cracked and lost all its engine oil.”

This is where the most important Dakar decision-making comes into play. Do you try to carry on? Wait for another rider to help? Wisely, he chose to ride back to a refueling point where Meoni’s mechanic was able to help Price re-plumb some oil lines to keep the precious lube in the normally drysump engine, bypassing the cracked in-frame tank. He cruised at a conservative pace to that day’s finish.

Then there was the unfortunate cooling-fan incident.

“My radiator fans quit working in the sand dunes 60 miles into a marathon section,” Price says. “But instead of risking it, I played it safe.” This meant riding slower than nor-

mal to keep the engine cool, even going as far as to ride at night.

“I rode for 16 hours the first day and for 13 hours the next day with only 2 hours of sleep,” he says. “I was thrilled to finish that section.”

Although it was very difficult-or perhaps because it was so difficult-making the finish of that stage was one of the highlights of Price’s Dakar: “I saw a picture of me that a rider friend of mine took at the end and I can see the satisfaction in my eyes.”

These personal victories were highly rewarding, but the human side-the camaraderie of people who are competitors but all working toward the same goal-also hooked Price.

“I got together with a bunch of people who have the same twisted gene for speed that I do, all joined by the bond for riding,” he says. “I made some real good friends real quick on the rally.” As the race progressed, being physically ready was never a problem for Price. It was the mental game that played him the hardest. But crossing the finish line after 17 days and 5300 miles of hardship and adversity proved he was able to keep it all together. Many hadn’t. Only 98 of 162 starters made it to the finish this year. The rally took its toll on Roma again, who in the last eight years has never made it to the finish. He crashed out while chasing now three-time winner Sainct in the Libyan Desert. Meoni skirted disaster a few times during the rally, pushing his body and booming KTM Twin to the limit, always just making it to the end of each stage. Despite his efforts, he never succeeded in unseating Sainct. Frenchman Cyril Despres, also on a KTM Single, rode a smart race to finish second, just 7 minutes back, despite breaking his collarbone a few weeks before the start of the rally.

After some 90 hours of special sections, Sean Price finished in 80th place-some 36 hours behind Sainct-but that lowly spot in the running order wasn’t the point. Because after the $75,000 he’d spent to do the Dakar, it no longer was a dream. It wasn’t necessarily a reality, either. It had become, as it does for most, an addiction. And now he has to figure out how to go back.

“My wife says I can do it again, but only under one condition,” he says with a laugh. “I have to find a sponsor!” □

NHRA sponsors bail, but Harley soldiers on

These are hard times for NHRA drag racing teams seeking sponsorship.

Both the George Bryce-run organization backing three-time champion Angelle Savoie and Vance & Hinesbacked Matt Hines, himself a former NHRA Pro Stock champ, are standing down in 2003, hoping better economics lie beyond. The prosperity that seemed endless before 2000 is no more, and formerly strong sponsors must conserve cash to assure their own survival. A possible bright spot is that some sponsors in bigger arenas than drag racing may have to economize too-and could find the “1320” sport fits their diminished budgets nicely.

Until then, two of drag racing’s most successful racers are without rides for the 2003 season.

The Vance & Hines “V-Rod Concept Dragster” development is another mat-> ter, because its sponsor is Harley-Davidson, whose products seemingly never go out of style. Two years ago, V&H received funding to develop an entirely one-off V-Twin drag engine to exploit the 2600cc pushrod, twovalve window in the NHRA rules. The engine they would build has no Harley-Davidson parts in it, but there aren’t many offthe-shelf parts in the Suzukis, either. By the

numbers, the V&H motor looked very promising. Its design, implemented by means of modern technologies, looked just as good. The giant V-Twin, turning 8000 rpm, could make horsepower equal to that of the class-ruling Suzukis by just filling its cylinders as well as a 1960 Manx Norton did. That 325 horsepower looked so real that people viewing the numbers could almost hear and feel it. The machine was built and CW went to observe its first teething runs at the hallowed Los Angeles County Raceway strip. Making a big, deep growl, the Towering Twin moved off, keeping its tire spinning with casual assurance.

Despite all its good qualities, last season it failed to qualify. Power was good-its creator Byron Hines called it “a great dyno engine.” But it critically lacked overrev power-the ability to keep pulling across the second 1/8mile. Part of this was identified as an ignition anomaly, affecting timing. Also implicated was some lack of stiffness in rocker arms and the engine’s short pushrods. Because loads on reciprocating parts (valves!) increase as the square of speed, these stiffness issues are the very kind of thing you would > expect to affect performance above peak-power rpm. The top-of-the-class Suzukis pull strongly from 11,000 to 13,600 rpm, and their valvetrain stability has been refined over years of R&D. It’s hard to learn in a year what others have learned over many.

For this coming season, Byron Hines says a “new iteration” of the engine is ready. It carries new fuel-injection and ignition systems-chosen because of their makers’ reputations for product support. Information is power. Fuel pressure has been increased and nozzles and spray pattern refined.

Partly to help Harley-Davidson in the refinement of their engine-modeling software, the giant Twin has been modeled and there has been interchange between the V&H dyno and Harley as a means of pegging this “virtual engine” more firmly to reality. In the future, it is hoped this will be further refined to help optimize performance, possibly through friction reduction.

Hines also revealed that the engine’s intake airbox was not performing as hoped. This turns out to have been

quite common on Superbike racing Twins-both Aprilia and Ducati have re> homologated chassis to make room for larger airboxes. When one big cylinder is on its intake stroke, it pulls the pressure around its intake bell steeply downward, requiring airbox volume to keep the air coming. Superbike engines are only 38 percent as big as this one, so imagine the volume it requires! Hines noted a year ago that the engine had “packaging issues.”

V-Twins normally have problems with oil control because of their large per-revolution change of crankcase volume (in a Four, two pistons move up while the other pair move down, leaving case volume constant). To maintain a low density of entrained oil in the crankcase air, a Formula One car-like roots scavenge blower is used (like a tiny version of a AA-fuel dragster’s supercharger working to suck air out the crankcase) together with an air-oil separator. The resulting crankcase pressure hovers just below a half-atmosphere of vacuum.

The revised engine is now “close on the dyno-some areas are even better than the Suzuki,” Hines notes. Last year, he reckoned the bike to be 60 pounds overweight.

“We did pretty good on the bike-we took 35 pounds off it,” Hines said. He was especially pleased with engine weight, remarking that, “A Suzuki ProStock engine, less carbs, is 188 pounds. Ours, with its throttle bodies, is 208 now.”

This brings bike and rider to 570 pounds, 20 over minimum. Basic parts durability has been excellent, with the exception of a few over-hardened transmission gears that broke. Hines commented that the team’s paper trail worked-they traced all the failures to one process batch. In one of those gear failures an engine revved to 9800 rpm, producing an F-l level of piston acceleration. Crank, rods and pistons were fine. Cylinders stay round, seal well, and as revealed by minimum fretting against the case, don’t move around much. With some of its gray areas already filled in, and more work to come, stronger performances are expected.

V&H will run two of these bikes this year, the first ridden as before by Gary Tonglet, the second by Matt Hines’ younger brother Drew. Less weight and more overrev power will help. With Matt Hines’ program taking a year off, V&H’s full resources will be concentrated on the Twin. This coming season, the teams hope to put DNQs behind them and step up to a new performance level. -Kevin Cameron

Dan the Man: Eboz’s speed secret

Racing is a team sport, and nowhere is this more apparent than at the highest level. Don’t believe it? Then ask Kenny Roberts about Kel Carruthers, or Freddie Spencer about Erv Kanemoto.

For the past two seasons, the man behind Nicky Hayden’s AMA Superbike effort has been Dan Fahie. More than a mere mechanic, Fahie is part engineer, part cheerleader, part psychiatrist and 100 percent focused on helping his rider get the most out of his motorcycle on race day.

Fahie’s journey to the upper echelons of roadracing followed a familiar path.

In 1994, he joined fellow Canadian Jonathan Cornwell (himself now a top Öhlins technician) en route to Daytona, “Corndog” having little more than a Honda CBR600F2, a plan and a man named Dan in his van. Fahie was an accomplished off-road racer in> Canada, having won 125, 250 and 500cc motocross and cross-country regional championships in 1990 alone. And he’d tried his hand at roadracing, too, until a get-off derailed his program. Having done all the preparation on his own racebikes, he soon started working on other riders’ machines.

Because Southern California is the hub for factory race teams, Fahie knew he had to be here to get there-there being a full-time job as a factory mechanic. In 1994, he worked part-time for Steve Whitelock, and a year later moved to California to work at Jackson Racing, which makes hop-up parts for import cars. All the while, he made it known that he’d prefer to be working on bikes at the racetrack.

One thing led to another, and Fahie eventually got a call from Muzzy Kawasaki’s Steve Johnson, who offered him a tryout at a Laguna Seca test session in preparation for the 1997 season. Fahie landed a job as racer Todd Harrington’s chassis man, and from that point on, he was inside the inner-circle.

In 1998, Fahie was promoted to Doug Chandler’s 600cc Supersport

chassis man, and in his spare time impressed the likes of Ben and Eric Bostrom with his dirtbike riding abilities. The next year, Fahie was hired by American Honda’s Ray Plumb to work on Eric Bostrom’s 600, and the year after that Fahie worked on Nicky Hayden’s 600.

From 2001-02, Fahie was in charge of Hayden’s RC51 Superbike chassis, and the two became fast friends. When the heat was on, Fahie’s knack for keeping cool rubbed off on his rider, allowing them both to focus on the job at hand.

On top of his ability to ease stressful situations, > Fahie has a wealth of setup knowledge. What’s to know? Rake, trail, offset, swingarm length, swingarmpivot points...change one and it affects all the others, like a complicated geometry puzzle. And that’s before you throw tire choices into the equation! Let’s just say there is a lot to know. Fahie’s expertise is in taking riders’ seat-of-the-pants, laymen’sterms descriptions and turning them into engineering solutions.

With Hayden gone to Europe for 2003, Fahie is being reunited with Eric Bostrom as crew chief for the factory Kawasaki Superbike effort. New AMA rules this year allow for a 2mm overbore on 750cc Superbikes, which has changed the characteristics of Kawasaki’s venerable ZX-7R more than anticipated, making test time extremely precious.

Increased engine braking has been the biggest change, causing the rear end of the bike to want to “hack out” and try to pass the front under hard braking. Fahie and company have applied a Band-Aid fix of lengthening the swingarm, but it is just a Band-Aid. There’s never enough testing time.

“Eric rides the front a lot, so everything about the front end of his bike has to give him the feel he’s looking for,” Fahie says. “Keeping him happy is priority one as crew chief.”

When riders are happy and comfy, they’re more likely to push the bike to its limits, which is the only way to win races. As for Fahie, he says his biggest problem as crew chief isn’t making decisions, but resisting the temptation to jump over the wall and do the hands-on work himself.

With Bostrom having finished second to Hayden in the 2002 AMA Superbike title chase (winning his share of races along the way), and Hayden now gone to Europe to contest the MotoGPs, Kawasaki has an excellent chance of claiming the 2003 AMA Superbike Championship. With Dan behind the man, things look good.

Mark Cernicky

View Full Issue

View Full Issue