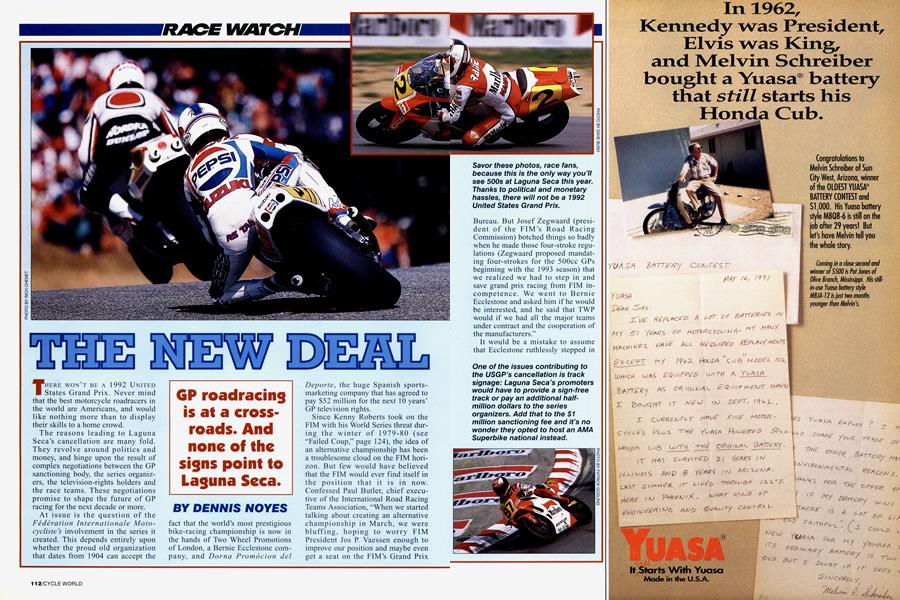

THE NEW DEAL

RACE WATCH

GP roadracing is at a cross-roads. And none of the signs point to Laguna Seca.

DENNIS NOYES

THERE WON'T BE A 1992 UNITED States Grand Prix. Never mind that the best motorcycle roadracers in the world are Americans, and would like nothing more than to display their skills to a home crowd.

The reasons leading to Laguna Seca’s cancellation are many fold. They revolve around politics and money, and hinge upon the result of complex negotiations between the GP sanctioning body, the series organizers, the television-rights holders and the race teams. These negotiations promise to shape the future of GP racing for the next decade or more.

At issue is the question of the Fédération Internationale Motocycliste’s involvement in the series it created. This depends entirely upon whether the proud old organization that dates from 1904 can accept the fact that the world’s most prestigious bike-racing championship is now in the hands of Two Wheel Promotions of London, a Bernie Ecclestone company, and Dorna Promócion del Deporte, the huge Spanish sportsmarketing company that has agreed to pay $52 million for the next 10 years’ GP television rights.

Since Kenny Roberts took on the FIM with his World Series threat during the winter of 1979-80 (see “Failed Coup,” page 124), the idea of an alternative championship has been a troublesome cloud on the FIM horizon. But few would have believed that the FIM would ever find itself in the position that it is in now. Confessed Paul Butler, chief executive of the International Road Racing Teams Association, “When we started talking about creating an alternative championship in March, we were bluffing, hoping to worry FIM President Jos P. Vaessen enough to improve our position and maybe even get a seat on the FIM’s Grand Prix Bureau. But Josef Zegwaard (president of the FIM’s Road Racing Commission) botched things so badly when he made those four-stroke regulations (Zegwaard proposed mandating four-strokes for the 500cc GPs beginning with the 1993 season) that we realized we had to step in and save grand prix racing from FIM incompetence. We went to Bernie Ecclestone and asked him if he would be interested, and he said that TWP would if we had all the major teams under contract and the cooperation of the manufacturers.”

It would be a mistake to assume that Ecclestone ruthlessly stepped in to take over bike racing. The man who turned Formula One car racing into a major TV sport on a worldwide basis-and who hopes to do the same for motorcycle racing-previously had some sour dealings with the FIM, though. These centered around Ecclestone’s thwarted bid to renew his contract for the series’ TV rights, which he held from 1987-91.

IRTA, with many complaints of its own against the FIM, and very concerned about the FIM’s plans to make drastic technical-regulations changes, saw a wronged and angry Ecclestone as a natural ally. The leading tobacco sponsors were uncomfortable with FIM leadership and in basic agreement with IRTA. And the Japanese and European motorcycle manufacturers were already skittish because of the FIM’s plans to replace fourcylinder 500cc machines with Twins. Then, when Zegwaard proposed fourstrokes for the 500cc GPs, the Japanese were so aghast that the Big Three actually wrote a letter to FIM President Vaessen stating flatly that they had no intention of building 500cc four-stroke grand prix machines. Insiders reported that Japanese executives no longer felt the FIM leaders were reliable or even predictable.

So, a series of FIM mistakes, both technical and diplomatic, turned what originally started as an IRTA bluff into an idea that increasingly seemed inevitable to all concerned-the classic right idea at the right time.

The turning point came when the FIM’s only powerful ally, Dorna, decided to join forces with Bernie Ecclestone rather than oppose him. When Ecclestone and Dorna’s British CEO, Richard T. Golding, sat down to talk, it became immediately apparent to them that the main obstacle preventing GP roadracing from taking off was the FIM itself, anchored in tradition and increasingly out of touch not just with the commercial side of racing, but with the technical side, as well.

All this was nothing new to Ecclestone, who had pulled F-l car racing into its present form more than a decade ago after a battle with its sanctioning body. Asked about his negotiations with the FIM, Ecclestone said, “It’s been like dealing with Formula One racing before the ’80s. You find a lot of sometimeswell-meaning people with very little knowledge. Then there are a lot of people who use the federation to gain some respect or power or recognition, but with no interest in what it does to the sport.”

From the moment that Ecclestone and Golding agreed to agree, the FIM’s power lessened. IRTA’s leaders, always suspicious of the FIM, would have preferred that the championship be run without the FIM, but both TWP and Dorna saw the advantages of retaining the FIM as an “umbrella.” Meanwhile, IRTA had signed a contract with TWP in which Ecclestone agreed to pay IRTA $600,000 per grand prix plus 50 percent of the TVrights revenue, with Ecclestone also

responsible for providing 12 to 14 safe tracks and a federation to sanction the events. This agreement has been modified and IRTA is now said to be taking somewhere between $800,000 and $1 million per GP to split among the teams, with significant increases in the money paid to riders finishing lower than 10th place. Additionally, IRTA has contracted 36 riders in the 125 and 250cc classes, and 30 riders in the 500cc class, who are prohibited by the conditions of their contracts from taking part in any other international championships.

IRTA’s leaders did a good job of keeping the pressure on the FIM and probably forced some mistakes that helped the rebel cause. IRTA faced a kind of public-relations crisis at mid season because everyone was expecting a major announcement at the British Grand Prix, home turf for the rebels. But at that time, IRTA was still an associate member of the FIM and was treading on delicate legal ground. Unable to announce the World Series, or even to talk about it on the record, IRTA pulled off a beauty of a media coup that was accomplished without a single direct quote.

It was “leaked” to the press that the alternative series would be headed up by tennis star Boris Becker’s manager, the colorful Rumanian Ion Tiriac. Tiriac, a most unlikely promoter of motorcycle racing, never denied having talked to Ecclestone about the series and even went so far as to say on the phone from Austria, “I am very interested in the possibilities.” But he never showed his amazing mustache at a GP, nor for that matter was he ever mentioned again by IRTA. Further Donington fireworks were provided by the handsome and debonair Max Mosley, a barrister frequently associated with Ecclestone. IRTA “leaked” that Mosley was working hard on the legalities of the alternative championship and that he would be at Donington. When Mosley arrived, IRTA secretaries and receptionists cooed, “He’s dreamy!”

Things were getting dreamy indeed.

Mosley would later unseat FISA (the federation controlling international auto racing) President JeanMarie Balestre, fueling rumors that if the FIM backed out of the TWPDorna deal, bike racing could be run under FISA sanction.

The FIM’s Vaessen himself faced the press in Mugello, site of the San Marino GP, and handled himself very well, offering IRTA the place it was seeking on the proposed Grand Prix Bureau. IRTA’s reply came at the Czechoslovakian GP, where the group’s general assembly voted to break with the FIM and actively work toward organizing an alternative championship. The FIM’s peace offer was taken as a sign of weakness.

Dorna, which controls an estimated 80 percent of sports programming in Spain and holds the advertising-signage contracts with 11 NBA basketball teams, is used to dealing with professionals, and had seen enough of the FIM’s muddled handling of the crisis. Its multi-million-dollar investment was being devalued, and it pushed for a three-way agreement between TWP, Dorna and the FIM that would avoid the nightmare of parallel world championships.

Currently, things are still up in the air. After all the political maneuvering and urgent meetings, the fact is that as late as halfway through January, nobody had a definitive grand prix schedule. And as this report is written, no one really knows if the FIM will even be a part of the championship scheduled and organized by TWP, with sporting regulations written by IRTA and with television and signage rights in the hands of Dorna.

If the FIM balks at the last minute,

the grand prix championship schedule will be announced by TWP and Dorna anyway, and what could have been a partnership between professionals and a sporting federation will, in fact, have become a takeover. The FIM, hedging against this possibility, has drafted regulations for an InterContinental Championship, which will allow the FIM to keep a world-

wide series up and running in the event that it decides to take on the TWP-Dorna-IRTA championship in the future. It is interesting to note that the technical regulations for the Inter-

Continental Championship, which would begin in 1993, specifies 600cc four-stroke engines of up to four cylinders, a variation of Zegwaard’s original, ill-fated proposal.

TWP and Dorna have made a big investment in motorcycle racing, and they expect a return on that investment. Only circuits that can afford to pay a $1 million sanctioning fee will be allowed to run GP races, which is the reason that there will not be a USGP in 1992. Not only that, but the circuit’s are required to provide a sign-free track, or pay an additional $500,000 to Dorna.

“The FIM has imposed conditions on us that are not acceptable,” said Mary Wright, public-relations director for the group that promotes the races at Laguna Seca. “Besides the $1 million sanction fee and $500,000 signage fee, they wanted to reschedule the race to August. That’s when we run our annual historic car races. We decided to pass on the GP, and have an AMA Superbike national in its place (April 24-26).”

In addition to Laguna Seca, Anderstorp (Sweden) and very probably the Salzburgring (Austria) have decided that the stakes are too high and have dropped out. But the majority of the current GP circuits are in. The New Deal is in place.

Questions remain, but in the best of all possible worlds, grand prix motorcycle roadracing will become a truly professional sport without losing its ties to 88 years of FIM tradition.

Dennis Noyes, an American living for the past 25 years in Barcelona, covers the grand prix scene for Solo Moto magazine, and is president of the International Road Racing Press Association.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontUncle George's Last Ride

April 1992 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Enchanted Vagabond

April 1992 By Peter Egan -

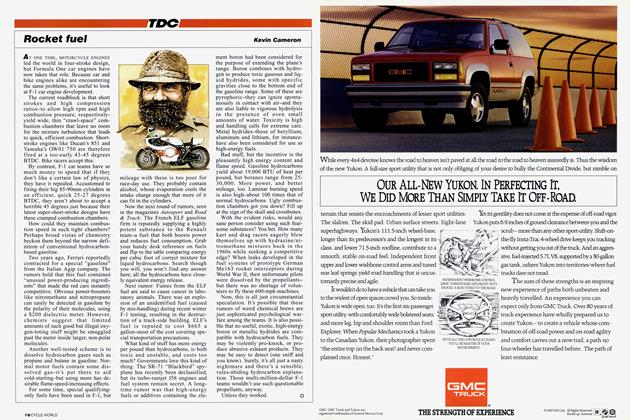

TDC

TDCRocket Fuel

April 1992 By Kevin Cameron -

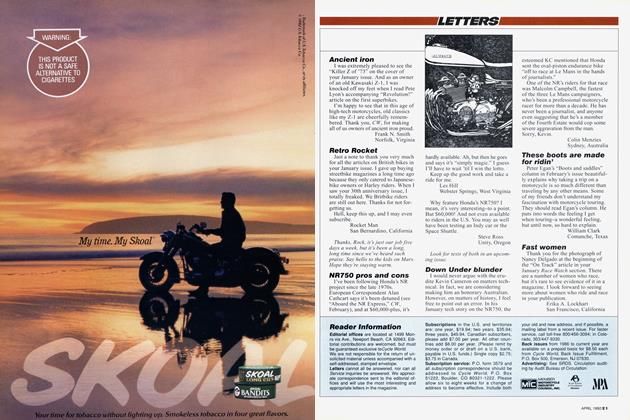

Letters

LettersLetters

April 1992 -

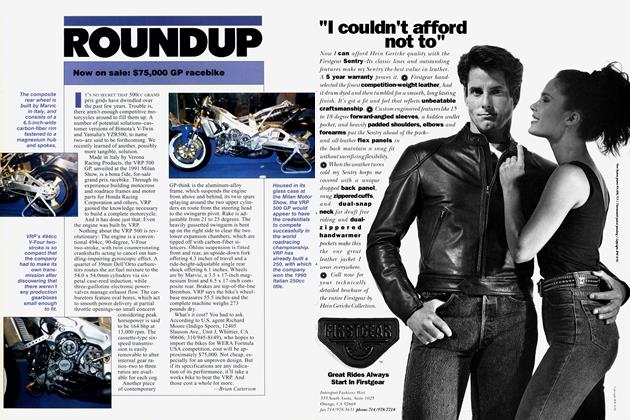

Roundup

RoundupNow On Sale: $75,000 Gp Racebike

April 1992 By Brian Catterson -

Roundup

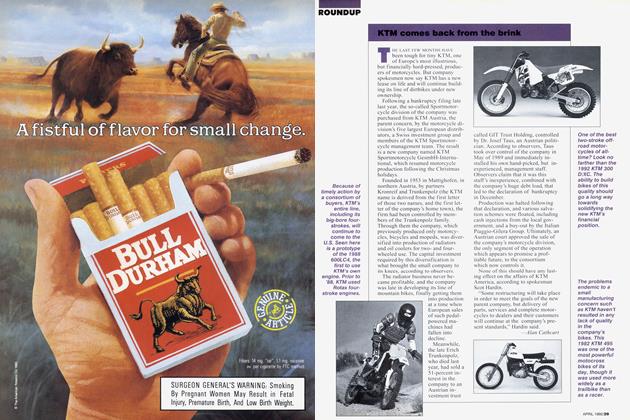

RoundupKtm Comes Back From the Brink

April 1992 By Alan Cathcart