Desert Panzer

Riding Jonah Street's Dakar stage-winning Yamaha WR450F racer

BLAKE CONNER

THE DAKAR RALLY IS BRUTAL ON BIKE AND BODY. THERE IS NO comparison in off-road racing; it’s like doing the Baja 500 solo every day for two weeks straight with just one rest day mercifully inserted into the middle.

For the past three years, the Dakar Rally has taken place more than 4000 miles away from its namesake destination in Dakar, Senegal. In 2008, the rally was scheduled to start in Lisbon, Portugal, and descend south into Africa, but terrorist activity forced organizers to cancel the race. With no sign of stability in western Africa, the rally moved to South America starting with the 2009 edition and seems likely to stay put for some time.

Several Americans have finished on the podium in the Dakar rally, including Danny LaPorte (second, 1992), former Cycle World Off-Road Editor Jimmy Lewis (third, 2000) and Chris Blais (third, 2007). But, most recently, America’s hope for podium success has rested on the shoulders of Washingtonian Jonah Street. With five Dakars under his belt, Street scored a best overall result of seventh ir 2010 and has two stage victories to his credit. Not bad for a privateer racing against competitors with million-dollar-plus budgets.

We recently had the opportunity to spend a day with Street and were able to pick his brain about all things Dakar before turning OffRoad Editor Ryan Dudek loose on Street’s rally-prepped Yamaha WR450F racebike.

It’s really not too hard to find a reasonable facsimile of Chile’s Atacama Desert here in Southern California; we simply headed to Dumont Dunes, on the doorstep of Death Valley, and its endless playbox full of sand. But as we discovered, when things seem too good to be true—like riding a bona fide stagewinning Dakar bike—they usually are.

First off, the bike wouldn’t start, and it wasn’t just the dead battery. Street hadn’t seen the bike since the race-finishing Stage 13 in Buenos Aires, and somewhere between Argentina and the WR’s arrival at our photo studio, someone had snipped a bunch of wires in the harness, rendering the engine inoperable. But, like he’s had to do many times during competition, Street used the resources on hand—in this case, a few Cycle World stickers in lieu of electrical tape—and repaired the wiring. A few kicks later, the engine blatted to life.

Dudek, himself a pro-level off-road racer, then threw a leg over to get acquainted. If there were ever an off-road machine that requires some getting used to, this is it. “First thing you notice is that the seat height is noticeably taller than stock,” said Dudek. “The saddle is a borrowed replacement for Street’s custom unit that fell off on Stage 6 of the rally. It isn’t at all comfortable; my butt hurt after just an hour, and I was standing up half the time!”

And the bike isn’t just tall, it’s big and heavy, carrying 9.25 gallons of fuel (7.1 more than standard) when its three separate gas tanks are topped off to minimize time at a standstill for refueling and dramatically increase range at racing speeds. This bumps the already hefty rally-kitted, 333-pound Panzer (sans fuel on CW’s scale) closer to 400 lb.

With such a huge variation in weight between full and empty tanks, suspension settings are truly a compromise. “It’s pretty frustrating in some places, and in other places it’s actually nice,” said Street. “We try to set it up for half-full tanks, but it also depends on the terrain we expect to encounter. It’s rarely perfect.”

Even with the tanks near empty, the extra weight of the rally equipment gives the WR strange handling characteristics that make it difficult to ride. Said Dudek, “The bike likes to be controlled with input from your legs and feet through the footpegs instead of primarily steering with the bars. And you really have to adjust to the additional width of the two front tanks between your knees. Once you lean it into a turn, gravity takes over and the weight in-

stantly becomes an issue.”

Considering that Street’s bike had not been touched since being brutalized on the rally, it was in better-than-expected condition. But that’s not to say it was in good condition. “The suspension was wasted and almost useless when hitting big g-outs or transitions,” said Dudek.

“You simply take the abuse and pray for the best. But the worst aspect was the

worn-out steering-head bearings; the play in the front end made it feel as if the wheel was going to fall off at any moment. Now imagine hitting an unseen ravine at 50, 60 or 70 mph. The bike is really hard to handle, and doing it for 10 hours a day would be punishing.”

To say the least.

In 2011, rally rules were changed and the displacement limit was dropped to 450cc in the hopes of attracting more competitors. This shut the book on the radical 700cc Singles that had previously dominated. Street’s WR450F engine was left bone-stock, both for budgetary and reliability reasons, since he was definitely not one of the million-dollar factory babies. Figure about 45 horsepower working in this heavy package. “There wasn’t much bottom-end,” said Dudek.

“It took more-than-normal clutch work to get response at lower rpm because of the weight and tall gearing, but once moving, the bike was pretty fast. One issue was that it didn’t want to wheelie, which would make it difficult to pop the front wheel up over a bump easily.”

Scan for more photos and video

cycleworld.com/dakar

One aspect that Dudek didn’t get to experience was the complete navigational package. The GPS that all competitors use in the rally is issued by Dakar organizers and repo’d at the conclusion of the event.

“The dashboard navigation setup is complicated,” Dudek said. “Think about using a roll-chart for a map, and then add traditional enduro timekeeping computers and a GPS system. Now, use and keep all of that organized in your mind at speeds as high as 100 mph in an unfamiliar desert.”

What does Street think is the most important element about staying on course? “When you pull into the bivouac at the end of the day, the organizer gives you the road book for the next day’s stage,” explained Street. “Basically, you have to learn to interpret the road book. The hardest part is learning the scale of each [navigation] note as it relates to your environment in the desert. Every note is

on a different scale. So, you may have an entry that refers to a section of road that is 5 kilometers long and then the next couple of notes may refer to a series of turns that are just a few tenths or less apart. The GPS system only actually guides your route when you are within 800 meters of a waypoint, so most of the navigation is via road book until you get really close to the waypoint. The waypoint usually registers on the screen about 100 meters before you actually get to it, so you learn that you need to ride another tenth before you zero out your computers for the resets in the road book to be accurate. Finding the waypoints is especially important when you are in the sand dunes with no other reference. But primarily, I use the GPS for its compass setting.”

On the final day of this year’s Dakar, Street had a minor crash, tipping over onto the right side of the bike. What he didn’t know at the time was that the lower mounting bracket for the very expensive JVO Racing right-side fuel tank

had been pushed into contact with the exhaust header.

After 13 hellish stages and 6000 miles, Street headed into Buenos Aires and crossed the finish line in a disappointing 14th place. Mechanical gremlins on two separate occasions had gotten the best of him, dropping him down the order from as high as sixth; but he and his WR had survived Dakar.

Street was fortunate that there wasn’t another stage, because during our test ride in the dunes, the pipe finally melted through the tank and the bike caught fire! We were able to extinguish the flames without trouble, but that incident underlines how easy it is for things to go terribly wrong due to a seemingly minor problem. Even without that “14th-stage” fire, our lasting impression of Street’s WR is how used the bike felt and how overwhelming it would be to combine all the elements necessary—navigation, physical endurance and riding skills—to succeed in the Dakar Rally.

Major props to Street and his bike for even surviving. But maybe next year we can ride his bike before the race... U

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Mysteries of Grandpa

JULY 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

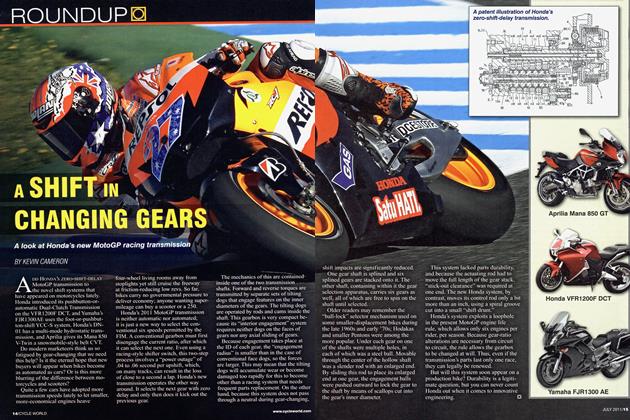

Roundup

RoundupA Shift In Changing Gears

JULY 2011 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupBmw S600rr

JULY 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

Roundup“chrome” Hawk

JULY 2011 By John Burns -

Roundup

RoundupCycleworld.Com Poll Results

JULY 2011 -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago July 1986

JULY 2011 By Blake Conner