SERVICE

PAUL DEAN

Kawai-shaky

I just purchased a 2011 Kawasaki Vulcan Vaquero 1700cc, and the vibration it produces at low rpm is substantial. The dealership says this is a characteristic of the engine. My question is, what can I do to reduce the vibration of this motorcycle? I know I may not be able to get rid of all the vibration, but just reducing it would be great. I love the looks of this bike and just need some guidance. Jon Busby

Bakersfield, California

What your dealer told you is correct—sort of; the shuddering you are feeling at low rpm is indeed a characteristic of the Vaquero engine.

But it is not “vibration” in the typical sense, because it is not caused by any rotating or reciprocating imbalance; it instead is the result of the large and unevenly spaced power pulses of the bike’s big V-Twin engine. It is most noticeable at low rpm because the pulses are comparatively far apart; at higher rpm, they are so closely spaced that the effect is greatly lessened.

To help mitigate those pulses, Kawasaki’s other saddlebagged 1700cc V-Twins (Voyager and Nomad) have damper springs incorporated into their outer clutch hubs. That clutch design combines with a large spring-loaded “cush” mechanism on the crankshaft’s primary drive gear to act like shock absorbers that help soften the effect of the power pulses. When designing the Vaquero, however, Kawasaki’s engineers purposefully omitted the clutch-hub damper springs so that riders would feel more of the engine’s V-Twin pulsations. And no, that was not a diabolical move on Kawasaki’s part; for a very large number of V-Twin riders, power pulsations are part of the charm that has made motorcycles with those types of engines so attractive.

For you, the good news is that the outer clutch hubs on all of Kawasaki’s 1700cc V-Twins are interchangeable. This means you can, if you wish, install a hub from a Voyager or Nomad. Though that will not completely eliminate the shuddering you feel at low rpm, the spring-equipped clutch hub should

reduce it to a level that you will find acceptable.

The bad news? Those clutch hubs retail for about $550, and you’re also looking at somewhere in the neighborhood of $100 in labor charges for installation. But if that expense helps you better enjoy a motorcycle that cost more than $16,000, it will be bucks well-spent.

Live to rev, rev to live

QI CBR600F3, recently bought and it a is ’97 my Honda first sportbike. I have put almost 2500 miles on it, and I’ve been wondering if bikes like this are better if run at higher rpm and if it also is better to shift at higher rpm. I guess my real question is, does revving sportbikes at high rpm hurt the engines or not? Nathan West

Posted on America Online

A Unless you are talking about spending all of your riding time bouncing the engine off its rev limiter, high rpm will not harm your CBR600F3. Its engine was designed to

run at higher revs, with peak torque arriving at 10,000 rpm and peak power at 12,000, as well as a 13,500-rpm redline and a rev limiter that kicks in a couple of hundred revs higher. The two rpmrelated matters that are most hazardous to an engine’s longevity are piston speed and valve float, and those concerns are dealt with by the manufacturer’s engineers as part of the original design process. Prototype and pre-production engines are run on dynamometers for long periods at all rpm to determine longevity. If something fails, that area of the engine undergoes analysis and redesign to eliminate the likelihood of it happening again. With very rare exception, an engine has proven its reliability many times over before it reaches production.

Conversely, there’s nothing wrong with riding and shifting at lower rpm, either, although you should avoid lugging the engine at very low rpm in the higher gears. That puts much more strain on key engine and driveline components than riding at high rpm. Even though engines like the one in your F3 proved very capable on racetracks around the world, they were designed first and foremost as versatile street engines that can operate safely anywhere within their entire rpm range.

The lowering lowdown

Ql’m some writing insight in into hope the of lowering getting of a streetbike. My current ride is an ’89 Suzuki GSX600F Katana, and I’m ready to upgrade to a Honda CBR-RR. My only concern is the 32-inch seat height of the CBR vs. the 30-inch height of the Katana’s seat. I was thinking I would lower the CBR because even on the Katana, I cannot stand flatfooted. What is the correct way to lower a bike? I’ve been told that I can just buy a lowering link, but I have also been told I must lower the front suspension, as well. I am sure there are problems in changing steering geometry or wheelbase. Is it worth the cost and possible danger of lowering a bike (or even buying one that has been lowered) or should I choose a bike with a lower seat height?

Adam Hendrick Middletown, Connecticut

A There is no “danger” involved in lowering a motorcycle when it is done properly and the rider understands the dynamics of such a change. If you use a good-quality rear lowering link,

also lower the front of the bike and are aware of and comfortable with any compromises that might result, you should be pleased with the outcome.

I said “should” because I do not know enough about your riding preference s—or how far you would lower the CBR—to say that you will be pleased. You are planning to upgrade from an older sportbike to a newer and much sportier one, which indicates that you perhaps like to ride the twisties or participate in track days. If that’s the case, the most meaningful compromise will be a reduction in cornering clearance. And if you are a reasonably aggressive sport rider, that reduction could be enough to not only limit your speed around corners but possibly cause a lowside crash when some hard part prematurely slams the pavement. This is the only circumstance that could insert any real danger into the picture.

If fast rides on backroads and track

days are not part of your agenda, however, there should be no major compromises. The rear ride will be a little stiffer, since the suspension will have less travel available to deal with bumps. But if you lower the front by precisely the same amount as the rear, there will be no change in steering geometry and only a tiny reduction in wheelbase. The net result should be a bike that still handles very much like it did before but with less cornering clearance and a slight harshness in the ride.

Incidentally, the easiest way to lower the front is just to slide the fork legs up in the triple-clamps. The only caveat is to ensure that the front fender does not hit the bottom triple-clamp or fairing under full compression. The best method of checking for adequate clearance is to remove one fork spring and then compress the fork until it bottoms internally before making contact with anything else.

Adjustment shimilarities

I usually do my own service on my 2008 Honda CBR1000RR, and I was looking through the manual to see what it says about doing a valve adjustment because I am actually past the recommended 16,000-mile service interval. The manual contains a note that states: “Use genuine Honda parts shims specific to this model for replacement. In case of wrong shims usage, the intake valve titanium surface may be damaged.” I also have a 2001 CBR600F4Í for which I’ve accumulated a fair number of shims, so 1 asked my dealer about it, and he said that they all use the same shims, and there are no differences. Before I actually use my existing shims, I’d like to be confident that there are not some shims that are “specific to this model” that I need to get. Any help in resolving this question in my mind would be greatly appreciated. Keith Danielson

Submitted via www.cycleworld.com

A Not to worry, Keith; the shims

for your 2008 1000 and 2001 600 have the same part numbers, so they obviously are interchangeable for both of your bikes.

Actually, all other dohc Honda models with shim-under-bucket valve adjustment use the very same shims. I’ve tracked the part numbers all the way back to the 1990 VFR750F, and they remain unchanged right up through the RC3Ö, RC45, ST 1100, ST 1300, RC51, VTR1000 Super Hawk, 919, 599 and all the CBR-RRs—600, 900, 929, 954 and 1000. Which makes perfect sense; with about 70 different shim thicknesses available, it would be a manufacturing and inventory nightmare for Honda and its dealers if every bike with this method of valve adjustment required its own unique shims.

No hot-testing needed

QI am curious to know if motorcycle engines are hot-tested before they are installed in a new bike. Working in the commercial truck business, I have had the opportunity to visit Detroit Diesel and Cummins engine manufacturers. I’ve seen their research and hot-test areas (very cool, by the way), and each engine is tested before shipping and installation. This raises a question about motorcycles and their recommendations for rpm limits and varying the rpm during break-in, and in most cases, requiring first service at or

before 1000 miles. Do motorcycle OEMs hot-test their engines? And are their recommended break-in proce-

dures related to whether or not the engine is hot tested? Mark S. Steffens

Plano, Texas

A Nope, motorcycle engines are

not “hot-tested” before shipment. After a bike has been completely assembled, it is started and run briefly on a set of rear-wheel rollers to determine if the engine functions properly, the transmission shifts, the lights and horn work, etc. But that is only a very brief test to ensure that the bike is ready to be crated for shipping.

With companies like Detroit Diesel and Cummins, it’s a different story.

They don’t make complete vehicles; they instead build engines that are sold to companies that manufacture trucks. Consequently (and no doubt as a condition of their contracts with those companies), they must ensure that the engines are in proper operating condition before leaving the plant. If a problem is detected with a new engine after its assembly or an initial adjustment is required, the engine companies have everyone and everything needed to remedy the matter. The truck manufacturers, however, likely do not and instead expect to receive engines in perfect running order that are ready to put on the road.

What’s more, since diesels burn fuel that is, to a certain extent, a low-grade

lubricant, they can go a lot farther between oil changes—and, I assume, before the first service—than engines that burn gasoline, which is an anti-lubricant that causes oil to degrade much more rapidly. For the aforementioned reasons, your matchup of diesel and motorcycle engines is interesting but really an

oranges-and-apples—or, perhaps more accurately, an oranges-and-tangerines— comparison.

Long live the UJM

QHow long will the modern “Universal Japanese Motorcycle” last before it needs an overhaul?

I have a 2010 Kawasaki Z1000, and I’ve already put 13,000 miles on it in 10 months. I’ve taken two teeth off the rear sprocket so it turns fewer rpm on my long freeway commutes. I use synthetic motor oil that is changed every 2500 to 3000 miles, have maintenance done by the dealer, and I only rarely hit redline.

I ask this vague question because my other bike is a 2006 BMW K1200LT with well over 100,000 miles on the clock, and it’s barely using half a quart of oil every 6000 miles. Other BMW riders tell me of going 300,000 to 500,000 miles before the first valve job. On the other hand, I know a V-Twin rider who does a complete overhaul every winter. Your insight is appreciated.

Steve Whittaker Arkadelphia, Arkansas

A For the most part, the lifespan of a typical UJM is largely in the hands of its owner. Just last month,

I replied to a letter from the owner of a 2003 Suzuki V-Strom 1000 that had racked up 195,000 miles and was still on the road. It’s a V-Twin, of course, not an inline-Four, but it was built with the same technology, materials and manu-

facturing techniques as an inline-Four. I’ve known or have met owners of various UJMs who accumulated more than 100,000 miles on their bikes without major overhauls, including one rider in particular whose 2001 Suzuki Hayabusa is nearing the 200,000-mile mark but has never required any engine work.

Any time I encounter someone who has a high-mileage bike, regardless of its manufacturer, I always try to ask questions—who does the maintenance, how often, any problems along the way, what kind of riding they do, etc. Invariably, the owners of these bikes tend to be a bit on the fanatical side, people who take an almost religious approach to the care and feeding of

their motorcycles. Conversely, when I meet riders whose bikes have been chronic problem children, as often as not, I quickly get the sense that routine maintenance is not quite at the top of their priority lists.

You didn’t specify the brand of V-Twin that gets an annual overhaul, but I suspect you were talking about a Harley-Davidson, perhaps even an older one. Back in the Panhead, Shovelhead and even, to a certain extent, the Evo days, Harleys were known to need frequent maintenance, especially if ridden far and often each season, but they didn’t usually require a complete rebuild every year. Nonetheless, since Harley Big Twins are essentially refinements of the same simple original design that dates back to the 1930s, combined with the fact that many H-D owners prefer to do all the work on their bikes themselves, the rider you mentioned may choose to rebuild his engine every winter more as off-season entertainment than as an absolute necessity.

Frankly, neither I nor anyone else can accurately predict the lifespan of any motorcycle, regardless of brand. As

Got a mechanical or technical problem with your beloved ride? Can't seem to find work able solutions in your area? Or are you eager to learn about a certain aspect of motorcycle design and technology? Maybe we can help. If you think we can, either: 1) Mail a written inquiry, along with your full name, address and phone number, to Cycle World Service, 1499 Monrovia Ave., Newport Beach, CA 92663; 2) fax it to Paul Dean at 949/631 -0651; 3) e-mail it to CWlDean@aol. corn; or 4) log onto wwwcycleworld.com, click on the "Contact Us" button, select "CW Service" and enter your question. Don't write a 10page essay, but if you're looking for help in solving a problem, do include enough infor mation to permit a reasonable diagnosis. And please understand that due to the enormous volume of inquiries we receive, we cannot guarantee a reply to every question.

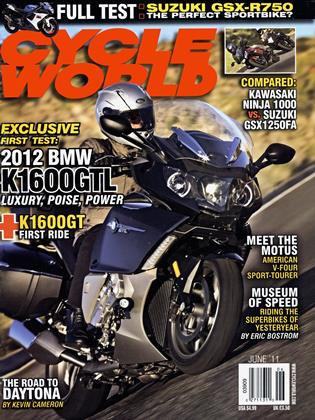

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontA Japan In Need

JUNE 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupAmerican Sport-Tourer

JUNE 2011 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

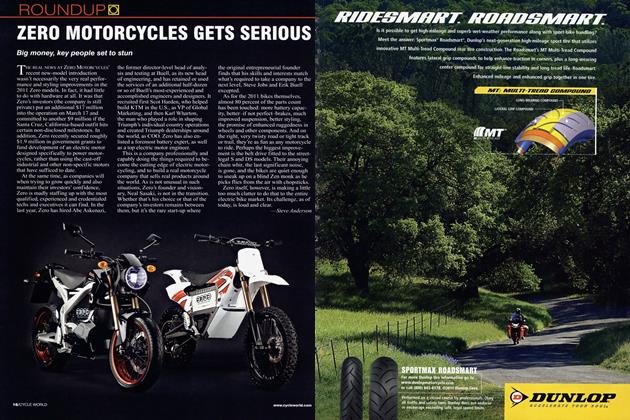

RoundupZero Motorcycles Gets Seriou

JUNE 2011 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

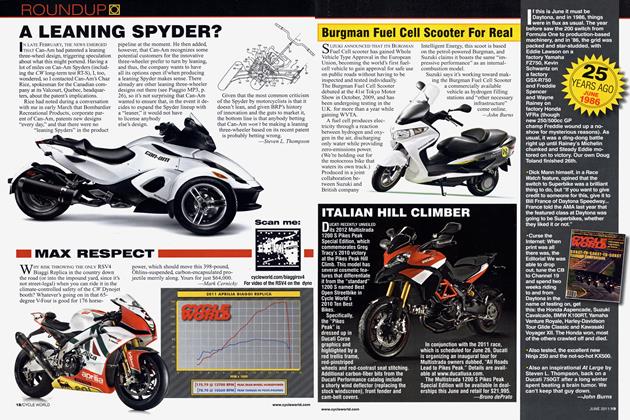

RoundupA Leaning Spyder?

JUNE 2011 By Steven L. Thompson -

Roundup

RoundupMax Respect

JUNE 2011 By Mark Cernicky -

Roundup

RoundupBurgman Fuel Cell Scooter For Real

JUNE 2011 By John Burns