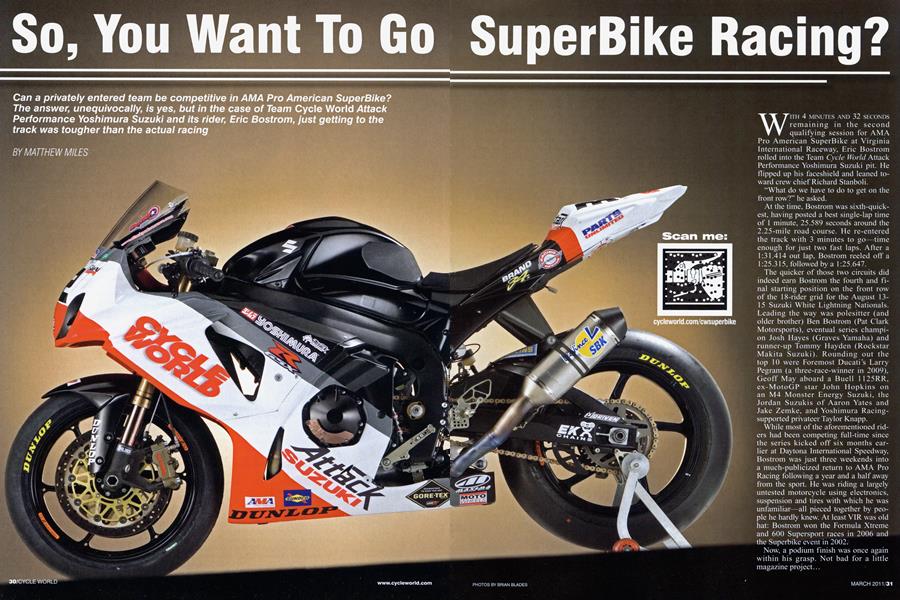

So, You Want To Go SuperBike Racing?

MATTHEW MILES

Scan me:

cycleworld.com/cwsuperbike

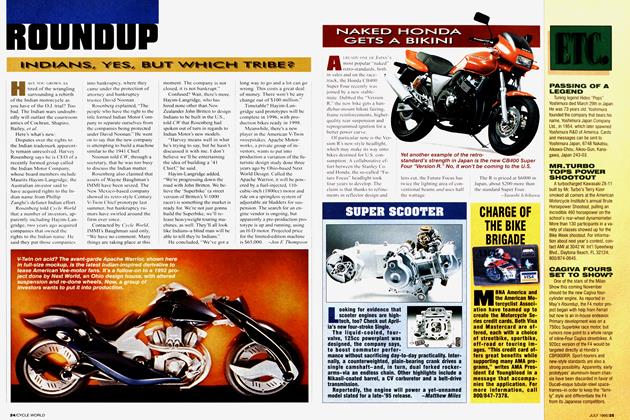

WITH 4 MINUTES AND 32 SECONDS remaining in the second qualifying session for AMA Pro American SuperBike at Virginia International Raceway, Eric Bostrom rolled into the Team Cycle World Attack Performance Yoshimura Suzuki pit. He flipped up his faceshield and leaned to-ward crew chief Richard Stanboli.

“What do we have to do to get on the front row?” he asked.

At the time, Bostrom was sixth-quickest, having posted a best single-lap time of 1 minute, 25.589 seconds around the 2.25-mile road course. He re-entered the track with 3 minutes to go—time enough for just two fast laps. After a 1:31.414 out lap, Bostrom reeled off a l :25.315, followed by a 1:25.647.

The quicker of those two circuits did indeed earn Bostrom the fourth and final starting position on the front row of the 18-rider grid for the August 1315 Suzuki White Lightning Nationals. Leading the way was polesitter (and older brother) Ben Bostrom (Pat Clark Motorsports), eventual series champion Josh Hayes (Graves Yamaha) and runner-up Tommy Hayden (Rockstar Makita Suzuki). Rounding out the top 10 were foremost Ducatis Larry Pegram (a three-race-winner in 2009), Geoff May aboard a Buell 1 125RR, ex-MotoGP star John Hopkins on an M4 Monster Energy Suzuki, the Jordan Suzukis of Aaron Yates and Jake Zemke, and Yoshimura Racingsupported privateer Taylor Knapp.

While most of the aforementioned riders had been competing full-time since the series kicked off six months earlier at Daytona International Speedway, Bostrom was just three weekends into a much-publicized return to AMA Pro Racing following a year and a half away from the sport. He was riding a largely untested motorcycle using electronics, suspension and tires with which he was unfamiliar—all pieced together by people he hardly knew. At least VIR was old hat: Bostrom won the formula Xtreme and 600 Supersport races in 2006 and the Superbike event in 2002.

Now, a podium finish was once again within his grasp. Not bad for a little magazine project...

Cycle World's deep dive into professional roadracing began innocently: over lunch in November, 2009, with ’07 Daytona 200 winner Steve Rapp. Like many of his peers, Rapp didn’t have a ride—or any leads, even—for the 2010 season. I suggested that our ’09 Suzuki GSX-R1000 testbike, prepared by Stanboli (Rapp’s former crew chief at Attack Kawasaki), using Yoshimura’s new engine-lease program, combined with the across-class-equality of seriesmandated Dunlop tires and Sunoco fuel, might be competitive under new American SuperBike rules.

Rapp liked the idea. Stanboli, however, wasn’t so sure. He’d just opened a new shop—the Attack Tuning Center in Huntington Beach, California—which was commanding his full attention. More to the point, he was still smarting from the way he felt he’d been treated in 2009 by both AMA Pro Racing and Kawasaki, which had pulled out of the series at the end of the season.

“I want to work with you'' I emphatically told Stanboli. “If you say no, this project ends here. I’m not shopping it around.”

“Okay,” he relented. “I’ll do it.”

We planned a three-round, five-race West Coast swing—Auto Club Speedway, Infineon Raceway and Mazda Raceway Laguna Seca. Suzuki sent me the title to the magazine’s GSX-R1000 and authorized a parts budget. Yoshimura promised to build the engine and include its EM Pro ECU, which controls fuel injection and engine mapping, engine braking and pit-lane speed. Dunlop agreed to supply tires for three rounds, plus one test. Brembo, Öhlins, LeoVince and MotoWheels began shipping brakes, suspension, exhaust systems and wheels to Stanboli’s shop.

We even came up with a charitable element: At the conclusion of the project, the ready-to-race machine would be auctioned off, with all proceeds going to the Cycle World Joseph C. Parkhurst Education Fund to benefit the Pediatric Brain Tumor Foundation’s scholarship program for brain-tumor survivors.

Hey, racing is easy!

Not so fast. Rapp picked up a full-time gig with Latus Ducati in the Daytona SportBike class and bowed out. Stanboli tapped as a replacement another former rider, 2009 AMA Pro SuperSport Champion Leandro Mercado. When he, too, became unavailable, I phoned 1993 500cc World Champion Kevin Schwantz. He suggested ex-factory KTM 125cc Grand Prix rider Cameron Beaubier, who had just won the Daytona SuperSport race on a Rockwall Performance Yamaha YZF-R6. Schwantz said he’d coach the 17-year-old Californian in his SuperBike debut.

So, in mid-March, AMA Pro Racing agreed to grant Beaubier a temporary SuperBike license, as well as cover our entry fees and related costs. Schwantz contacted Aldo Drudi of Drudi Performance, who penned a great-looking graphics package in traditional Cycle World colors, which was then brought to life by Paul Finn of 614Paintworx. Alpinestars made a matching custom leather suit for Beaubier.

Due to parts delays and the aforementioned rider changes, Round 2 of the series at Auto Club Speedway in Fontana, California, quickly became an impossibility. I announced the project in the June, 2010, issue, informing readers that “Team Cycle World will compete in select American SuperBike events, beginning with the May 14lb West Coast Moto Jam at Infineon Raceway in Sonoma, California. We have also entered Round 7 of the series at Mazda Raceway Laguna Seca, to be run in conjunction with the Red Bull U.S. Grand Prix, July 23-25. More events may follow.”

The project was back on track—or so I thought.

In late April, during a heated international conference call that included Schwantz, Stanboli, CW Editor-inChief Mark Hoyer and Yoshimura’s Don Sakakura, newly hired series race director David McGrath informed us that AMA Pro Racing was not going to issue Beaubier a SuperBike license—temporary or otherwise. He said Beaubier didn’t have any “big-bike” experience and hadn’t earned enough points to make the jump from SuperSport to Daytona SportBike, never mind American SuperBike.

McGrath acknowledged that AMA Pro Racing had made a mistake, but that didn’t make the situation easier to stomach. Based on the AMA’s earlier decision, I’d made calls, pitched the project to prospective sponsors both inside and outside of the motorcycle industry, rounded up parts and published our plans. Everything was in place—except the rider.

To his credit—though unbeknown to CW—McGrath had a backup plan: get four-time national champion and 15-time Superbike race-winner Eric Bostrom to ride the bike.

“I’d been in Brazil for three months and a lot before that,” said Bostrom sometime later. “I was probably spending 50 percent of my time there. Ben was a little bit worried for me and wanted to get me home or at least in a controlled environment where he knew I was safe—on a motorcycle.

“When I spoke with David [McGrath], he said, ‘There’s an opportunity to ride a bike that should be first-class.’ At first, I was like, ‘Man, I don’t know how realistic that is. We’re coming into the season, everybody’s already hot and I haven’t ridden a motorcycle in a year and a half.’ Everything was a bit of a question mark—my concentration, my fitness. Not to mention all of the loose ends that I had to tie up.

“But, to my surprise, I wasn’t able to sleep that night. I guess I’d been suppressing my emotions, which was that two wheels are my life. I didn’t realize just how much I missed it. The next morning, I got out my computer and typed, ‘I’m in.’”

Bostrom traveled from Rio de Janeiro to San Francisco for the team launch, which was held at Infineon Raceway in conjunction with the AMA national. The static debut was a collaborative effort: Stanboli and Dan Schwartz finished prepping the bike, then pushed it into a van, which Jon Bekefy of LeoVince drove up the California coast to Sonoma, where his boss, Tim Calhoun, had set up a redcarpet Q&A session with fans and media. Luxury-leather-goods-maker Michael Toschi hosted a party later that night for the team at his San Francisco store.

“Bostrom was clearly excited by the prospect of racing a competitive machine in the series’ top class,” I wrote in the August issue, “particularly at two of his favorite tracks: Mazda Raceway Laguna Seca and Virginia International Raceway. Bostrom has never won at Barber Motorsports Park, the final stop for the series this season.”

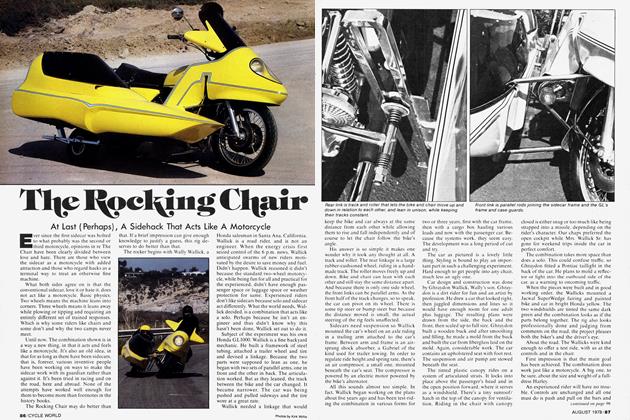

Testing began the first week of June. A solo shakedown at Spring Mountain Motorsports Park near Pahrump, Nevada, was followed by two days with established AMA teams at Barber Motorsports Park. At Spring Mountain, Bostrom was impressed with the GSX-R. “One of the steps forward was a really big front-end slide. The motorcycle didn’t do anything strange; it just corrected itself.”

Barber, however, was a reality check. Heavy engine braking topped a long list of problems. At the end of the first day of testing, Bostrom had posted the ninthquickest time, a 1:27.823, which was nearly 2 seconds slower than top-man Hayden. “To be that far off the pace was disheartening,” Bostrom admitted.

Day 2 was better. “We got the bike sorted out a little bit, and the smile came back on my face,” said Bostrom. “Then, about six laps into the session, the chain jumped off and I kind of ruined the motorcycle—and myself.”

By mid-afternoon, bike and rider were once again back on track. More changes were made. Lap times improved. Then, another crash.

“I left Barber thinking, ‘Well, the first day was really bad,’” said Bostrom. “But we made some progress, and I was gaining confidence in the team.”

After the test, Stanboli outlined five areas of crucial importance: 1) travel budget; 2) spare bike; 3) spare engine; 4) spare parts; and 5) more-capable ECU. “What we are doing is not easy, and it takes a boatload of money,” he concluded.

At the outset of the project, no one had expected Beaubier to win SuperBike races. Steady progress on his part—a top-eight finish, for instance—would have equated to success. Bostrom, however, was capable of winning. Stanboli contended that the $1925 EM Pro system provided by Yoshimura was too limited—at least in as-delivered form. The deceleration portion of the map, for example, was not even activated.

Seven years ago, Stanboli had purchased a MoTeC electronics system for $8000. He was intimately familiar with its rich capabilities and latest updates. “I suggest we use our MoTeC system so that we have full capability,” he said. After hearing Stanboli’s explanation, Sakakura agreed.

Sakakura also agreed to supply a second engine built to Yoshimura’s latest performance spec—identical to that used by Knapp. The crashed Barber test engine would be our spare. Redline for both powerplants was 14,000 rpm.

From the very beginning, I’d been working on sponsorship for the team. When Parts Unlimited heard about the project and, in particular, Bostrom’s involvement with it, the Wisconsinbased distribution giant wrote a check for $10,000. That money went directly to Stanboli. Who knew that a semi was so expensive to run and maintain? Diesel fuel alone for the one-day Spring Mountain test cost $600.

W.L. Gore, maker of Gore-Tex, Windstopper, LockOut and other biker-friendly innovations, also kicked in $10K. I spent most of the Gore money on liability insurance and track-rental fees, setting aside the remainder for Laguna Seca hotel and travel expenses. “Grim” best described the outlook for another cross-country run for the doubleheader race weekend at VIR in August and a return trip to Birmingham for the series’ September season finale. We simply didn’t have funds sufficient to compete at those rounds.

Scott Tedro was our financial savior. President of Sho-Air International, a global shipping and asset-management company, Tedro is also the founder of the Team Sho-Air/Specialized professional mountain-bike team and US Cup off-road racing series.

“Scott was curious about [the project],” said Bostrom. “He was like, ‘This guy should be racing at the front. Yet the team’s struggling because they don’t have what they need to get the job done.’”

Tedro called me, and we set up a dinner meeting. We were joined by Bostrom, Schwantz and Stanboli. Schwantz suggested that the best way to get Bostrom back up to speed would be to enter the July 16-18 Honda Super Cycle Weekend at the Mid-Ohio Sports Car Course. Bostrom could run in traffic and be better prepared for Laguna Seca two weeks later. Bostrom, Stanboli and Tedro agreed.

Tedro authorized Stanboli to buy a second GSX-R1000 from a local Suzuki dealer. He also guaranteed funding for spare parts, travel expenses and additional tires. In total, Tedro would spend $75,000. For the next two weeks, Stanboli and mechanics Dan Schwartz and Jim “JJ” Matter worked non-stop. They built a second racebike from the ground up: Yoshimura engine, Brembo brakes, Öhlins suspension, OZ Motorbike wheels, Motion Pro Revolver throttle and entire Attack Performance catalog—bodywork, clip-on handlebars, rearset foot controls, triple-clamps, rearwheel lift kit, etc. They also wired up the MoTeC controller and machined various aluminum odds and ends, not to mention a million more last-minute tasks. On the last day of June, Matter rolled the GSX-R onto the CW dynamometer. Breathing through a titanium 4-into-2 LeoVince exhaust, the Yoshimura engine spun out 180.86 horsepower at 12,785 rpm and 78.63 foot-pounds of torque at 10,775 rpm—a gain of 16.26 hp with a loss of 2.07 ft.lb. compared to the stock numbers.

During the next six weeks, we ran five races at three venues—Mid-Ohio (eighth, DNF), Laguna Seca (seventh) and VIR (seventh, DNF). Bostrom’s come-from-behind run at Laguna and spectacular front-row qualifying effort in Virginia raised a few eyebrows and boosted his confidence.

Downside was that Bostrom hadn’t posted a result that he was proud of. “It was acceptable to finish eighth at Mid-Ohio,” he said, “because it was my first race back. But after that, we should have finished sixth, then fifth, then fourth.” Stanboli held a different view: “Our performance at VIR proved that you can build a competitive SuperBike.”

Bostrom struggled with starts. Part of his problem was that the series-spec Dunlop slicks were better than he expected. “The front tire is great—Dunlop has always had a great front tire,” he said. “When I left the series, the rear was either hit-or-miss. With the new spec rear, you can just go. And that’s what the competition was doing. Their fastest laps were at the beginning of the race. My lap times improved as the race went on—as I got comfortable with the bike and what it was doing.

“I never thought I would say that I’m a fan of a spec-tire rule, but I love it. I think the racing is way better.”

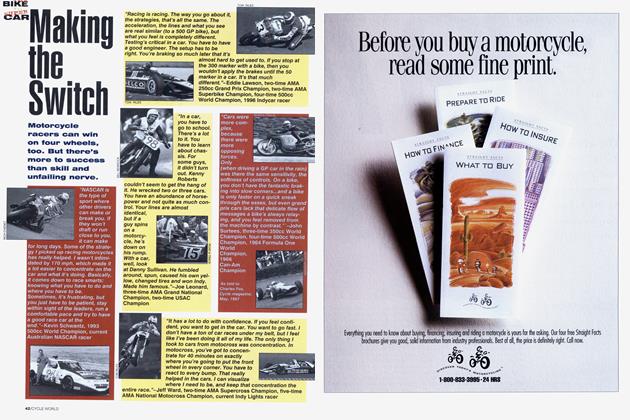

At the series finale at Barber Motorsports Park, Bostrom qualified fifth-quickest—just 0.161 of a second behind Hayden and 0.542 adrift of polesitter Blake Young. His best lap, a 1:26.096, was 1.5 seconds quicker than he’d gone during the June test. Before Saturday’s race, Eric got a pep talk from his brother. “It’s like diving,” said Eric. “You can’t ‘half’ dive. You just have to dive. That’s basically what Ben was telling me: ‘You’re ready.’”

Bostrom jumped the start, laid back per AMA rules, then charged from ninth at the end of the first lap to fifth. He was reeling in Young, who would win on Sunday, but running out of laps. On the final circuit, in the penultimate corner, Jordan Suzuki’s Brett McCormick (stand-in for the injured Yates) attempted a Hail Mary pass and rearended Bostrom, knocking both riders to the tarmac. The collision ripped open Bostrom’s left thigh—narrowly missing his femoral artery and nerve—leaving behind a gaping wound that required three hours of surgery and 102 stitches to close. Just like that, our season was over.

I was disappointed, but in some respects, I was also relieved. I had no idea what I was getting into with this project. I’d never run a racing team, and I certainly gained a lot of respect for those who do. I quickly discovered that I was ultimately responsible for the welfare of the project, for making it go, for moving it forward. All the while, I had to continue my full-time job as a magazine editor.

I’m deeply proud of Team Cycle World Attack Performance Yoshimura Suzuki and what we achieved in such a short time span and against difficult odds. The on-track results, along with insights into aspects of the project for which there simply isn’t space here, were documented in previous issues and can also be found online at cycleworld.com.

Of course, this project never would have moved off Top Dead Center without the support of everyone involved, including the people at AMA Pro Racing. I expected great things from Richard Stanboli, and he over-delivered on every level. Likewise, our mechanics, Dan Schwartz, Jim Matter and Todd Fenton, and truck driver Don Baynes. Eric Bostrom showed the courage, fortitude and skill that some wondered if he still possessed.

I always knew that racing was hard, but until this project, I never fully understood how hard it is, and not just on the track but off it, as well. It’s much easier to go backward than forward. Yet we kept moving forward—as a team. All the way to the end. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue