BY THE NUMBERS:MV Agusta F3

ROUNDUP

Is the new Triple a serious threat?

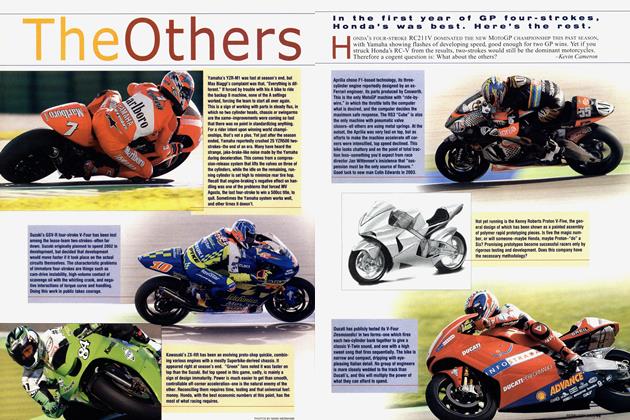

WHEN A NEW MACHINE COMES ALONG and information is scarce, I begin exploring possibilities. Recently, MV Agusta revealed that it had developed a three-cylinder 675cc machine with 138 horsepower. Poking around the Internet suggests this bike has been in development for at least two years, delayed by uncertainty over the company's future. Now that Harley has sold the MV operation back to the Castiglionis, that is resolved-at least for the moment.

The new Triple is said to have a backward-rotating crankshaft, along with what have become standard sporting Euro-bike features (ride-by-wire with multiple maps and traction control), and to be radically small and light.

This machine evokes the racing history of MV, which introduced a 500cc Triple in Grand Prix racing in 1966 that was much more compact, agile and lighter than the previous four-cylinder. That bike, in the hands of Giacomo Agostini, was able to defeat Honda’s conventional and less-handy RC-181 four-cylinder in 1966 and ’67, despite the Honda’s greater power. The same virtues are sought from this new MV Triple.

Available for comparison is Triumph’s 675 Triple, with dimensions of 74.0 x 52.3mm for a moderate bore/stroke ratio of 1.41. Its claimed 123 crankshaft hp comes at 12,500 and its peak torque is located very close for a four-stroke—at only 750 fewer revs. Stroke-averaged net combustion pressure at peak power is 189 psi, and 194 psi at peak torque. These are good figures for a production engine.

To make MV’s claimed 138 hp from the same displacement might require proportionately more rpm—that is, 138/123 = 1.12, or 12 percent more revs. That takes us to 14,000 rpm, which is certainly not out of the question, as some current lOOOcc Fours of similar cylinder size are already in that vicinity.

The Triumph’s pistons experience peak acceleration of 5750 g at 12,500, which would rise to 7200 g at 14,000. This latter number is close to the highest numbers now seen in 600 sportbike engines at peak revs. The higher the number, the sooner the accumulated fatigue causes cracks to appear in the pistons. If we changed the bore/stroke ratio to 1.6, we would not be at an ex-

treme; Ducati’s original Testastretta 1000, at 104.0 x 58.8mm, had a ratio of 1.77. A 1.6 ratio would give us a Triple with 77.0 x 48.0mm dimensions. Now, at 14,000 rpm, our peak piston acceleration moderates to 6600 g, extending the life of the pistons.

The overarching principle is to make all the power you can from pressure, and only as a last resort to push rpm higher. If we worked a bit harder on port design and combustion, we might eke out a few percent that way and not have to push the revs as hard. This might give us an engine with a bit more stroke-averaged

combustion pressure—202 psi—at peak power. That would let our peak revs come back to 13,500 and our piston acceleration to 6100 g.

If our airflow department succeeded in boosting the numbers with smallish ports, we might also be able to push the rpm of peak torque downward, creating a wider, more usable powerband. After all, it’s not peak power that gets us to the next turn; it is engine torque, averaged across the rpm range actually used in the journey.

It’s fun to play with the calculator, but it’s all hot air until the real numbers are released. Kevin Cameron

View Full Issue

View Full Issue