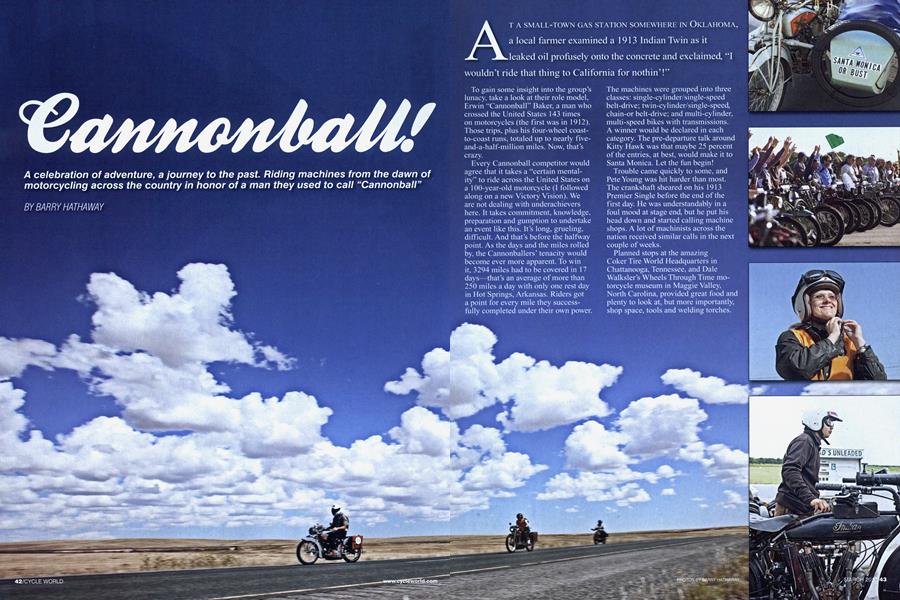

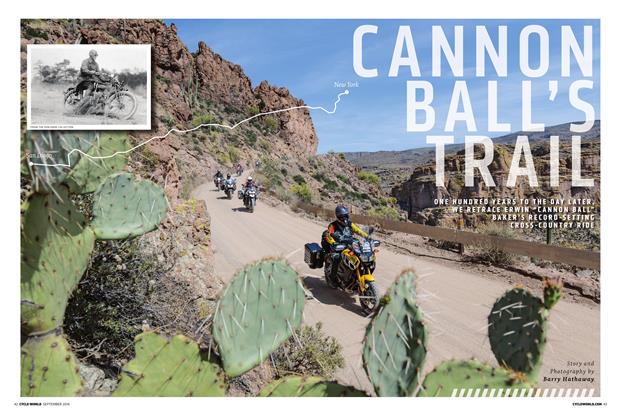

Cannonball!

A celebration of adventure, a journey to the past. Riding machines from the dawn of motorcycling across the country in honor of a man they used to call "Cannonball"

BARRY HATHAWAY

TA SMALL-TOWN GAS STATION SOMEWHERE IN OKLAHOMA, a local farmer examined a 1913 Indian Twin as it leaked oil profusely onto the concrete and exclaimed, “I wouldn’t ride that thing to California for nothin’!”

To gain some insight into the group’s lunacy, take a look at their role model, Erwin “Cannonball” Baker, a man who crossed the United States 143 times

on motorcycles (the first was in 1912). Those trips, plus his four-wheel coastto-coast runs, totaled up to nearly fiveand-a-half-million miles. Now, that’s crazy.

Every Cannonball competitor would agree that it takes a “certain mentality” to ride across the United States on a 100-year-old motorcycle (I followed along on a new Victory Vision). We are not dealing with underachievers here. It takes commitment, knowledge, preparation and gumption to undertake an event like this. It’s long, grueling, difficult. And that’s before the halfway point. As the days and the miles rolled by, the Cannonballers’ tenacity would

become ever more apparent. To win it, 3294 miles had to be covered in 17 days—that’s an average of more than 250 miles a day with only one rest day in Hot Springs, Arkansas. Riders got a point for every mile they successfully completed under their own power

The machines were grouped into three classes: single-cylinder/single-speed belt-drive; twin-cylinder/single-speed, chain-or belt-drive; and multi-cylinder.

multi-speed bikes with transmissions.

A winner would be declared in each category. The pre-departure talk around Kitty Hawk was that maybe 25 percent of the entries, at best, would make it to Santa Monica. Let the fun begin!

Trouble came quickly to some, and Pete Young was hit harder than most. The crankshaft sheared on his 1913 Premier Single before the end of the first day. He was understandably in a foul mood at stage end, but he put his head down and started calling machine shops. A lot of machinists across the nation received similar calls in the next couple of weeks.

Planned stops at the amazing

Coker Tire World Headquarters in Chattanooga, Tennessee, and Dale Walksler’s Wheels Through Time motorcycle museum in Maggie Valley, North Carolina, provided great food and plenty to look at, but more importantly, shop space, tools and welding torches. On both of these nights, as with many others to come, major repairs and adjustments were made through the wee hours, with some riders hitting the road the next morning with little or no sleep. One rider told me he’d had eight hours of sleep in four days. A precedent was being set: ride all day, wrench all night.

Safety was a legitimate concern on the event, with relatively sluggish, archaic machines sharing the road with high-horsepower modern vehicles that stopped on modern brakes. The organizers went out of their way to make sure everyone finished in one piece, even going so far as to mandate that all bikes were to be off the road by dark, in the interest of rider safety. Rider skill was a huge factor, especially on climbs and descents like Magazine Mountain in Arkansas and Sitgreaves Pass in Arizona. Some of the bikes, such as Vince Martinico’s 1914 Pope, had virtually no brakes even on a good day, and for many, tires were their only suspension—a nasty bump or a hole in the road could make things interesting real quick. The event’s youngest rider, 25-year-old Matt Olsen, found out the hard way when his 1913 Sears struck a deep pothole in Alabama and he hit the tarmac, breaking his nose and arm.

Dieter Eckel and his wife Katrin Boehner, the only non-U. S. competitors, shipped their bikes to Kitty Hawk from Bavaria and before long were giving the Americans fits. Yes, Dieter is a gentleman and Katrin is elegant, kind and soft-spoken, but it soon became apparent that their bikes just ran, and that was a real problem for the competitive Yanks. As early as Chattanooga, the tortoise-and-hare analogy (the hare and the hedgehog in Germany—no tortoises there) was being assigned to them. Yes, theirs were the slowest bikes, but they were regular like clockwork. And, well, we all know how that famous fable ends. The fairytale ended for Dieter in Arizona, though, when the fork on his 1913 BSA snapped in two without warning and sent him sliding across the tarmac. He suffered only minor scrapes and bruises and was back in the saddle the next day on his backup machine.

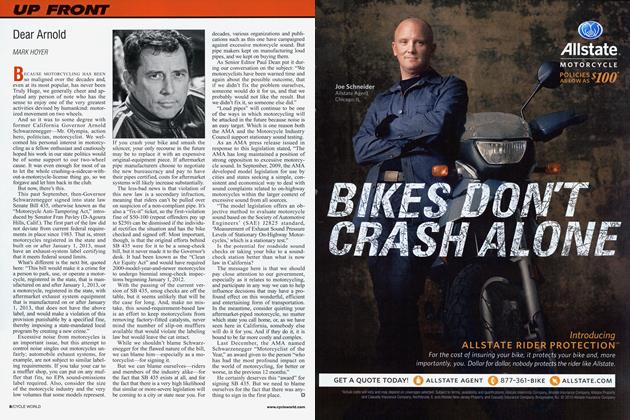

Not all was doom and gloom. Far from it. Some of the ancient bikes were having largely trouble-free runs. Crowds of curious well-wishers gathered along the route, hoping to catch a glimpse of history in the making. The excitement was contagious, and “Knucklehead” George (top right) caught the fever. George rode out to see the Harleys, Popes, Excelsiors, Indians, Hendersons and more go by in Greenville, and he decided, spur of the moment, to tag along on his ’47 Knucklehead hardtail chopper. “The Spirit moved me,” he explained with a chuckle. “One day turned into two, two into three, and before I knew it I was in the mountains.” No extra clothes, no tools, no toothbrush. And no rear suspension. George lives to ride, and not even a hip replacement and an artificial left knee can keep him off of his hardtail. “How often do you get to experience something like this?” he enthused. “Life can get so structured. This really does it for me.”

For Douglas Feinsod on his 1915 Indian (his tortured piston pictured at left), the Cannonball is meaningful on a different level. “This is the biggest test of this equipment at this scale, probably ever. This group is the core of the knowledge that exists on these bikes. This is very important, to share and proliferate this knowledge so it doesn’t disappear. The biggest reason I came on this trip was to be with other riders and mechanics, to tighten up our group. It’s one of the big experiences in my life.

We won’t let each other fail.”

It’s that kind of attitude that explains why only four of the 45 riders that left Kitty Hawk didn’t make it to Santa Monica.

Most days were scorching hot, others were freezing. Some were both.

Alan Travis was trembling and on the verge of hypothermia after his zerovisibility ride through the driving rain into Gallup, New Mexico, on his 1914 Excelsior boardtrack racer. “We earned our miles today,” he said. “It was really bad—the freezing rain. It was rough. I don’t have any suspension, so I need to really watch for potholes.”

Travis, like many other competitors, didn’t really know what he was getting into at the beginning. “It’s really another endurance event,” he said. “It’s like the Baja 1000 or Iron Man or other things that I’ve done in the past. I want to see if I can finish this with a perfect score. It’s harder than I ever thought it was gonna be. It’s the same as the Baja when you have trouble with your machine and you have to push through the night and hit all your checkpoints. This has turned out to be pretty hardcore. And the people in it are hardcore. A lot of people wouldn’t even try this on a modem bike.”

Dave Fusiak and others suffered from anxiety as California neared. “So far, I’ve been able to fix things, but every little noise, every little rattle... Normally, I’m a very relaxed rider, but I find myself riding tense because I hear something. I think that once we make it to the pier in California, our stress level will go to zero and we’ll have our grand day. We’ll look back on it and say that was really a lot of fun, but not while you’re doing it—riding 250 miles, then working on your bike for three hours, then working on somebody else’s bike for three hours. Then I’m laying in bed thinking, ‘What am I not doing to the bike?’ I want to get that perfect score.”

A California contingent of four riders arguably had a more relaxed approach to the whole thing. Steve Huntzinger and pals had a buddy since childhood, Stuart Munger, who passed away last year, before he could run the Cannonball with them. Their solution? A Mason jar containing Munger’s ashes rode the distance in one of Huntzinger’s Excelsior saddlebags.

“Sidecar Dudes” like British Tim, Canuck Jim and Mongo were the mobile medics of the event and added a lot of flavor. There was no sweeter sight to a stranded Cannonballer than one of these guys’ Panhead or Shovelhead with modified “flatbed” sidecar for transporting a sick Indian, Pope or Sears to the next service area. Tim shipped his Knucklehead all the way from Gibraltar, and all of them volunteered their time, money and machinery to make sure no one was left behind.

Famed custom-bike builder Shinya Kimura and co-rider Yoshimasa Nimi pulled their share of all-nighters, including a parking-lot engine rebuild to replace a crankpin on his Indian in Albuquerque. Two days earlier in Oklahoma, Shinya said, “I’m learning a lot and, unbelievably, I’m still rolling and the motorcycle is getting better. Many people are sharing information, sharing parts.” For Kimura, the best element of the Cannonball was the opportunity to learn. “We are, of course, competitors, but at the same time, we are family, heading to California. The riding is very difficult, physically and mentally. But I am really happy. Maybe everybody is really happy.”

And while all this fueling, riding, repairing, grinding, adjusting, rebuilding and sleep deprivation was going on, something bigger was happening: We were seeing America. Cotton fields stretching to the horizon, great rivers flowing powerfully south. Hot springs and twisty two-lanes in Arkansas, mesas and wide-open spaces in New Mexico. The Tupelo Hardware store in Mississippi (where Elvis’ mother bought him his first guitar), Helen Keller’s birthplace in Tuscumbia, Alabama. Armadillos on the road in Texas, tarantulas on the highway in Arizona.

Everyone who’s traveled long distances on a motorcycle knows there’s a lot of time to think, to reflect. Jim Petty found this to be true. “Out there on the road, it’s Zen-like. I’m thinking about a lot of things—my life, my work, am I doing the right things?” he wondered.

There’s romanticism in it, too. We rode some long stretches of the original Route 66. How many times had “Cannonball” Baker and others like him passed through these very places, gazing at the same mountaintops and sweeping landscapes that we saw? One could almost see them there, on the shoulder of the road adjusting a carburetor or having a picnic lunch.

Joe Gardela had one of the bestprepared, strongest-running bikes (a ’14 Harley), but even he was pushed to the limit. Leaving Arizona, the Cannonballers awoke to find frost on the seats of their bikes. Who knew it would be oppressively hot in a matter of hours? “The toughest day was coming out of Flagstaff,” said Gardella. “Many of the bikes, including mine, had magneto failures due to the 105-degree heat. A lot of these bikes have gone through torture. A lot of them wouldn’t make it back to Kitty Hawk. Except for the magneto, mine’s running as good as the day I left. I spent 10 months preparing that thing for this event.”

At times, the strain was visible on the faces of the riders. In New Mexico, it was clear that Jeff Decker just wanted it to end. But when the finishers finally reached the Pacific Ocean, the relief was palpable. “I’m glad it’s over,” said Pete Young. “I accomplished what I wanted to do, but not all of it was fun. Not very much of it was fun, actually.

It was a lot of hard work. You either accomplish amazing things or you get on

you get the truck and go home, and I’m just too stubborn to go home.” Katrin Boehner

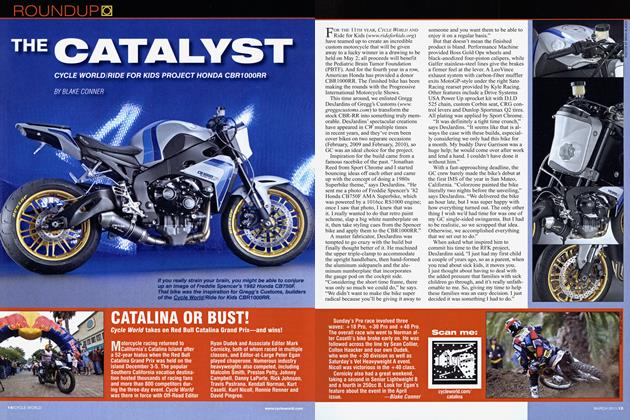

played the role of the tortoise (or the hedgehog) perfectly, right

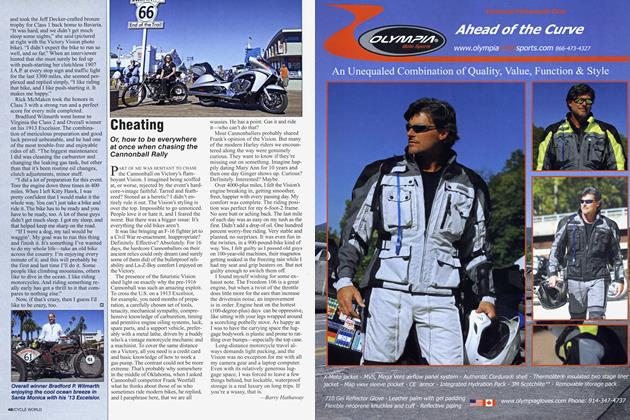

un tn thp pnrl and took the Jeff Decker-crafted bronze trophy for Class 1 back home to Bavaria. “It was hard, and we didn’t get much sleep some nights,” she said (pictured at right with the Victory Vision photo bike). “I didn’t expect the bike to run so well, and so far.” When an interviewer hinted that she must surely be fed up with push-starting her clutchless 1907 J.A.P. at every stop sign and traffic light for the last 3300 miles, she seemed perplexed and replied simply, “I like riding that bike, and I like push-starting it. It makes me happy.”

Rick McMaken took the honors in Class 3 with a strong run and a perfect score for every mile completed.

Bradford Wilmarth went home to Virginia the Class 2 and Overall winner on his 1913 Excelsior. The combination of meticulous preparation and good luck proved unbeatable, and he had one of the most trouble-free and enjoyable rides of all. “The biggest maintenance I did was cleaning the carburetor and changing the leaking gas tank, but other than that it’s been routine oil changes, clutch adjustments, minor stuff.

“I did a lot of preparation for this event. Tore the engine down three times in 400 miles. When I left Kitty Hawk, I was pretty confident that I would make it the whole way. You can’t just take a bike and ride it. The bike has to be ready and you have to be ready, too. A lot of these guys didn’t get much sleep. I got my sleep, and that helped keep me sharp on the road.

“If I were a dog, my tail would be waggin’. My goal was to run this thing and finish it. It’s something I’ve wanted to do my whole life—take an old bike across the country. I’m enjoying every minute of it, and this will probably be the first and last time I’ll do it. Some people like climbing mountains, others like to dive in the ocean. I like riding motorcycles. And riding something really early has got a thrill to it that compares to nothing else.”

Now, if that’s crazy, then I guess I’d like to be crazy, too. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue