SERVICE

PAUL DEAN

Cold-blooded Bavarian

Q I have an ’85 BMW K100RT with approximately 160,000 miles on it. When I start the bike in the morning, it idles very rough and will stall unless the fuel is enriched at 100 percent. After a few miles, the engine warms up and will run fine with the fuel enrichener closed. If it’s restarted warm, it runs okay, but if allowed to sit for a normal workday, it will run rough but warms up more quickly than it does if it sits overnight. Someone suggested that this may indicate a leaking fuel injector.

Dennis Bogusky Temperance, Michigan

A When you state that “the fuel is enriched at 100 percent,” I assume that means you push the coldstart lever on the left handlebar all the way to its full open position. But on your K100RT, that lever only affects idle speed; it has no impact whatsoever on the fuel mixture. Instead, enrichment is handled automatically by the fuelinjection system. When the system’s sensors tell the engine control unit that the engine is cold, the ECU responds by holding the injectors open a little longer during each duty cycle, thereby richening the mixture. As the engine warms, the mixture is gradually leaned until it reaches its normal mixture levels.

That’s how the system is supposed to work, at least, but it is not doing so on your BMW. And it’s my guess that one or more of three conditions are causing your engine to run erratically when cold: dirty fuel-injector nozzles, a faulty engine-temp sensor or a dirty fuel filter. Considering the high mileage on your RT, all three are logical possibilities.

You could start by checking or replacing the inline fuel filter. If it is partially clogged, it could be restricting the fuel flow enough to prevent the rich mixtures required for cold engine operation. If the filter proves not to be the problem, try running some of the commercially available fuel-injection cleaner through the system. Injector nozzles tend to accumulate small amounts of deposits over time, and even as little as a 5or 10-percent blockage can disturb the flow rate and spray pattern enough to cause rough running, especially when the engine is cold.

If one or two of those cleaning treatments improve the problem but do not cure it completely, you’ll at least know that dirty injectors are the culprit but that the deposits are too stubborn for over-the-counter chemicals to remove entirely. Instead, you’ll need to have the injectors professionally cleaned by a company that specializes in such services. You can find quite a few of them on the Internet by typing “fuel injector cleaning” in your browser, or perhaps one of the motorcycle shops in your area can direct you to a local company that does this kind of work.

If you find that neither the injectors nor the fuel filter are the problem, the next possible offender would be a faulty EFI sensor, most likely the one that monitors engine temperature. The only way to be certain, however, is to either replace that sensor (a waste of money if it does not remedy the problem) or have the EFI system diagnosed by a BMW dealer or a shop that has the requisite tester. All things considered, that last option makes the most sense.

ST means "steady temps"

QOn my 2006 Honda ST 1300, the temperature gauge always shows the same value, regardless of ambient temperature, riding conditions or the cooling fan being on or off. The gauge is actually a bar graph with 8 bars. Of course, when the engine is warming up from a cold start, the gauge actually moves (quite rapidly) from zero to 4 bars, but after warming, it always stays at 4 bars, which is halfway. I live in a country where I can easily ride in temperatures below freezing and, at the opposite, in the 90s while stuck in traffic. I should see some variations in the gauge level. Could you confirm what exactly this temperature gauge is indicating? My conclusion is that it just tells the rider that the engine is inside the acceptable operating temperature range.

But what happens if the engine overheats? Will it jump from normal to full hot in a matter of seconds, with no warning like a normal temperature gauge would provide? If so, it is no better than an idiot light.

If the reading is actually the water temp, how does the engine manage to have such a steady operating temperature regardless of any riding condition?

` Camille Descarries Montreal, Quebec, Canada

A Temperature-gauge readings that do not fluctuate are quite common among contemporary liquid-cooled motorcycle engines, and they accomplish that consistency primarily through the use of a thermostat, just like in car engines. A thermostat is a temperaturecontrolled valve assembly that resides in the cooling system between the engine and the radiator. It contains a small housing filled with a special material—usually some form of wax—that expands at a predetermined rate as its temperature increases and contracts as it decreases. The housing is connected to the valve itself in a way that causes the valve to open and close according to the temperature of the wax.

When the engine is cold, the thermostat is closed so that the coolant remains in the engine rather than circulating through the radiator. This helps the engine reach normal operating temperatures more quickly. As engine temps rise, the thermostat opens, allowing coolant to begin exiting the engine and passing through the radiator, where it loses a good deal of its heat. It then returns to the engine to carry away more heat of combustion before circulating through the radiator again. This cycle of circulation is constant when the engine is warm and running.

Although each thermostat is designed to open at a certain temperature, it does not do it suddenly like an on/off switch so that it’s either fully open or fully closed; instead, it opens progressively and often only partially. The degree of opening varies according to how much or how little the wax expands, which, in turn, is determined by the coolant temperature. The thermostat valve can be opened anywhere between just barely if the engine temperature is right near the designated point or wide open if the engine gets too warm.

This is how a thermostat keeps the temperature gauge on your ST 1300 showing the same value once the engine warms. The cooling system easily has enough capacity to keep the engine from overheating, and the thermostat regulates the temperature by constantly adjusting its opening. If the temperature starts to rise, the thermostat opens a little farther, allowing a greater volume of coolant to flow through the radiator, thereby stabilizing its temperature; if the temperature starts to drop, the thermostat closes just far enough to restrict the flow of coolant, again keeping the temperature stable. And if, for some reason, the coolant starts to get too hot, the electric fan kicks in and blows air through the radiator—though this usually only occurs when the bike is moving at low speeds.

ToolTime

I have no documentation to back this up, but I think it’s safe to assume that many more Harley-Davidson owners perform some level of engine work on their bikes than do owners of any other brand. After all, millions of Harleys have been sold over the years, a large percentage of which are still out there in one form or another, and they haven’t changed in basic design as much as other bikes have. On top of all that, the relative simplicity of H-D engines encourages owners to tackle major motor repairs and modifications themselves.

For the most part, that’s a good thing. But one of the mistakes I’ve seen home mechanics make far too often is a failure to keep contamination out of the engine. They tend to leave all of the many orifices, large and small, uncovered either while they’re working on another part of the engine or while it is stored awaiting parts or completion. Insects can then crawl unnoticed into small orifices, and dirt or other moredamaging debris can find its way into any of the openings, regardless of size. The end result can range from no harm whatsover to a problem that ultimately leads to yet another disassembly and repair.

For owners of ’99-to-present Twin Cam Harleys, JIMS Machining (www.jimsusa.com) offers a practical solution with its Twin Cam Engine and Trans Plug Kit (part #764, $64). It’s a 55-piece collection of enough caps and plugs to seal off every opening and orifice on any Twin Cam engine and transmission from Dyna to Softail to FL. The kit’s two large foam plugs have square holes cut through the middle so they can slip over a connecting rod and into the cyinder opening to prevent anything from accidentally falling into the crankcase. Smaller foam circles effectively close off intake and exhaust ports. An assortment of rubber and plastic caps is used for lifter bores and all of aTC engine’s numerous oil passages, and there even are some small rubber plugs that block off the oil lines themselves. Instructions explain which plug goes where, and everything stores nicely in an included clear plastic box.

Yeah, 64 bucks might seem a bit steep for a box of foam and plastic circles. But using them is a much more professional approach than stuffing a disassembled engine’s critical openings with rags and newspaper—or with nothing at all.

Where the rubber meets the rim

Q There’s a home tire changer in my immediate future, so I’m wondering how often motorcycle valve stems need to be replaced. I know the rubber ones on cars get replaced with every tire change, but the aluminum stems on my superbike are quite expensive as tire stems go; for that kind of money, I don’t want to be throwing away perfectly good ones. Of course, I also don’t want to throw myself or my bike away on the road because I was too stingy to replace a valve stem when it needed one. Scott Taylor

Lancaster, Pennsylvania

A My ability to provide a definitive answer often is limited by the amount of relevant information I receive in the question, and this is a good example. Not all valve stems are the same, and you did not identify the brand of aluminum stems fitted to your wheels; that makes it tough for me to offer specific advice about what to do with the stems during tire changes.

Rubber valve stems deteriorate due to exposure to ozone and UV light, whereas aluminum or steel stems do not; only the rubber gaskets on metal stems harden, crack and leak over time. But how much time? On most cars, new tires last tens of thousands of miles and several years, whereas those on motorcycles, especially sportbikes, usually are changed with much greater frequency. Thus, metal-stem rubber gaskets on motorcycle wheels are not as likely to require replacement during any given tire change as would those same gaskets or rubber valve stems on a car.

So, if you give the gaskets on metal valve stems a close inspection every time you change tires, you should be able to determine if they need to be replaced.

If I knew which brand of stems you currently are using on your bike, I might be able to tell you how and where to get replacement rubber gaskets. Some companies offer the gaskets separately, others do not. Several different types and styles of metal valve stems are sold at auto parts stores, especially those that specialize in racing equipment. Some of the better outlets even carry a wide enough selection of rubber grommets and gaskets that you might find what you need among them. If you’re willing to do a little research, you should be able to track down a source for inexpensive replacement gaskets to fit your valve stems.

Around the water-cooler

This must seem like a dumb question, but what are the important differences between air-cooled and water-cooled engines? I’m planning to buy a new bike very soon and have been checking out a few different V-Twins, some that are air-cooled and some that are water-cooled. Is one type more reliable than the other? I like one of the water-cooled bikes more than the others, but I’m sure it is more complicated than the air-cooled ones, and I don’t want it to leave me stranded in a remote area when something in its cooling system fails. Are my concerns legitimate or am I just being paranoid? Andy Gorman

Submitted via www.cycleworld.com

A I’d have to say it’s the latter, Andy. Liquid cooling is a long-standing, highly refined technology that dates back more than 100 years for automobiles and almost as long for motorcycles. There’s nothing “newfangled,” trendy or undiscovered about it.

But each system does have its advantages and disadvantages. Air cooling obviously is simpler, since it requires no water pump, radiator, thermostat, hoses, coolant and water jackets in the heads or cylinders, or even a temperature gauge on the instrument panel. This means no possible cooling-system leaks or related hardware failures. But when stopped or moving slowly, air-cooled bikes don’t cool very effectively because insufficient air is passing through the engine’s fins; even under other normal conditions, the operating temperatures of air-cooled engines can vary all over the map, since they have no means of controlling how much heat is being drawn away from the engine at any given time.

Liquid cooling, however, can control operating temperatures over a much narrower range through the use of a thermostat (see “ST means steady temps,” p. 69) and, when necessary, an electric fan that can automatically switch on and force air through the radiator if the temps get too high. This higher level of temperature stabilization makes meeting emissions standards a much easier task for liquid-cooled engines than for air-cooled ones. It also can contribute to better fuel mileage, more consistent performance and longer engine life.

Some people will argue that liquidcooled motorcycles direct more engine heat toward the rider and passenger. With some bikes, this is true, but usually only certain ones with full fairings on which heat from the radiator has no means of escape except out through the rear of the fairing and into the cockpit area. But some air-cooled bikes also try to fricassee the legs of their occupants due to heat radiating directly from the cylinders, so any decisions related to this matter are dependent upon the specific motorcycle under consideration.

My suggestion here is straightforward: Buy the motorcycle you like the most, regardless of its cooling medium. If it does what you expect it to do, you won’t give a damn how its engine gets rid of its heat.

KLR cruising concerns

QI love my Kawasaki KLR650 but am concerned about the rpm it turns when cruising at 60-70 mph. At that speed in top gear, the tach reads around 5000 rpm. I’m sure the motor is over-engineered and under-stressed, but is it really okay to cruise along for a couple hours with the motor spinning that fast? I thought of going to a larger countershaft sprocket to lower the highway rpm, but first gear already isn’t as low as I’d like for fire-roading, so that is not an option. Is it cool to ride the bike along the highway at 5000 rpm for extended periods of time? Scott McDonell

Long Beach, California

A Relax and enjoy the ride; you could cruise your KLR at five grand all day every day without fear of damaging the engine as a result.

One of the most important elements of engine design is maximum piston speed, which, if exceeded, can crack pistons and pull connecting rods apart. Motorcycle companies therefore tend to limit max piston speeds on streetbike engines to somewhere in the 4200-feetper-minute range. This provides a comfortable safety margin that allows engines to cruise at high road speeds without a serious risk of catastrophic failure. Many racing engines reach piston speeds that far exceed 4200 fpm; but they usually don’t come with warranties, they receive rebuilds and maintenance much more often, and their lifespans are only a fraction of what is expected of street engines.

At 5000 rpm, your KLR’s piston speed is just 2723 fpm, and it doesn’t hit 4000 fpm until close to its 7500-rpm redline. So, it is well within its safety margin when run at 60 or 70 mph for extended periods.

No go on the pogo

QI recently purchased a 1996 Triumph Trophy 1200, and it has an intermittent mushiness in the front end. There’s almost a tendency for the front to “pogo stick” over anything but perfect roads. The effect is somewhat slight and almost like I’m imagining it, but I don’t think I am. The fork oil and seals were supposedly changed recently by the previous owner, but I don’t know what weight oil was used, and I don’t see any leaking. Is the mushiness and pogo-stick sensation related to fork oil or something else? Is there a premium progressive fork spring available that would make an improvement? Jim McCracken

Twin Lakes, Wisconsin

The Trophy 1200 was known to have soft front springing, so you’re not imagining anything. And yes, the behavior of a fork is directly related to its fork oil. The thinner the oil, the “mushier” the fork will feel; the amount of front-end compression and “dive” (what happens when the front brake is applied) is also partially determined by the amount of oil in the fork.

Over the 13-year lifespan of the Trophy (1991-2003), Triumph changed the fork oil specification several times, ranging from 10W at a level of 103mm from the top of the fork tube to 10W-20 at 133mm. I’ve never personally tuned a Trophy front suspension, but a few people who have done so suggest using 15W fork oil set to a level of between 117 and 125mm, depending upon rider weight and riding style. That measurement must be taken with the springs and spacers removed from both legs and the front end then compressed all the way.

The reason fork behavior varies with lighter or heavier oil is simple: As the fork compresses and rebounds, the oil is forced through small openings in the damper mechanisms; the thinner the oil, the more quickly the fork can move.

Not so obvious is the reason that fork dive can be adjusted to a certain extent by oil level. As a fork compresses, the smaller-diameter tubes gradually slide inside the larger-diameter tubes, displacing some of the area inside of both; and because a liquid cannot be compressed, the displacement of internal area means that the oil level must rise. The farther the stanchions are pushed into the legs, the more the internal area decreases, forcing the oil to rise even higher. But air can be compressed; so, as the oil level rises, the air above it is squeezed into a smaller and smaller space, adding to the resistance already provided by the fork springs. The smaller the air space above the oil, the greater its “compression ratio,” just like in an engine. So, in effect, the air above the oil is part of the fork’s overall spring rate. This is why using a higher oil level, which results in a smaller air space above the oil, can reduce front-end dive when braking and produce a firmer ride.

I don’t know of anyone who makes progressive fork springs for a Trophy 1200, but Race Tech (www.racetech. com) sells straight-rate springs (part # FRSP S3732; $109.95), along with its Gold Valve Cartridge Emulator Kit (part # FEGV S4301; $169.95) to fit your Triumph. The springs have a stiffer rate and the emulators greatly improve the damping characteristics.

Got a mechanical or technical problem with your beloved ride? Can’t seem to find workable solutions in your area? Or are you eager to learn about a certain aspect of motorcycle design and technology? Maybe we can help. If you think we can, either: 1) Mail a written inquiry, along with your full name, address and phone number, to Cycle World Service, 1499 Monrovia Ave., Newport Beach, CA 92663; 2) fax it to Paul Dean at 949/631 -0651; 3) e-mail it to CW1Dean@aol.conr, or 4) log onto www.cycleworld.com, click on the “Contact Us” button, select “CW Service” and enter your question. Don’t write a 10page essay, but if you’re looking for help in solving a problem, do include enough information to permit a reasonable diagnosis. And please understand that due to the enormous volume of inquiries we receive, we cannot guarantee a reply to every question.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

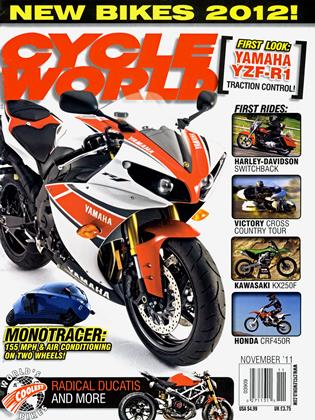

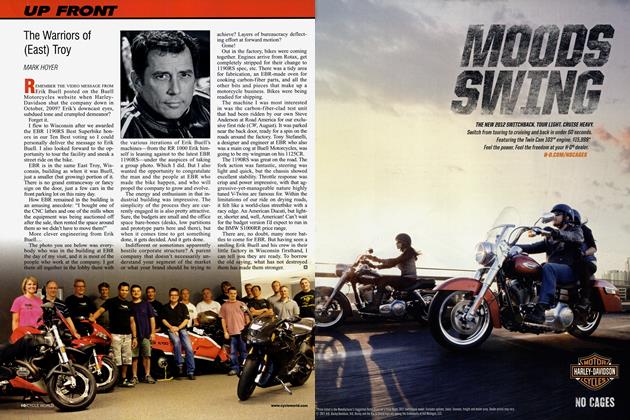

ColumnsUp Front

November 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

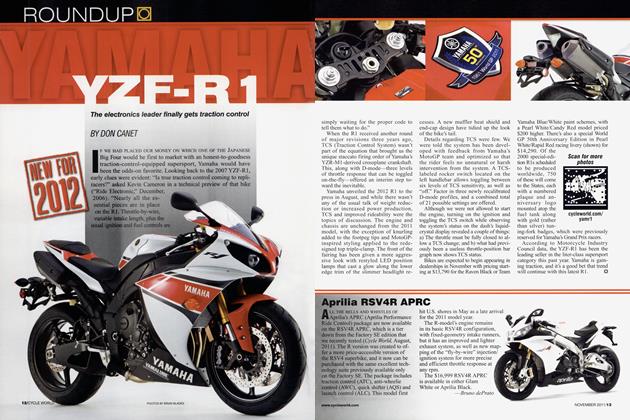

RoundupYamaha Yzf-R1

November 2011 By Don Canet -

Roundup

RoundupThe Future of Mx?

November 2011 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupMission Accomplished: Rapp Wins At Laguna

November 2011 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupFonzie's Triumph To Auction

November 2011 By Robert Stokstad -

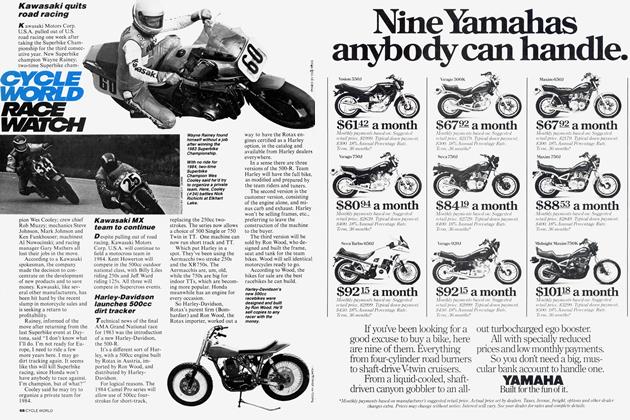

25 Years Ago November 1986

November 2011 By Don Canet