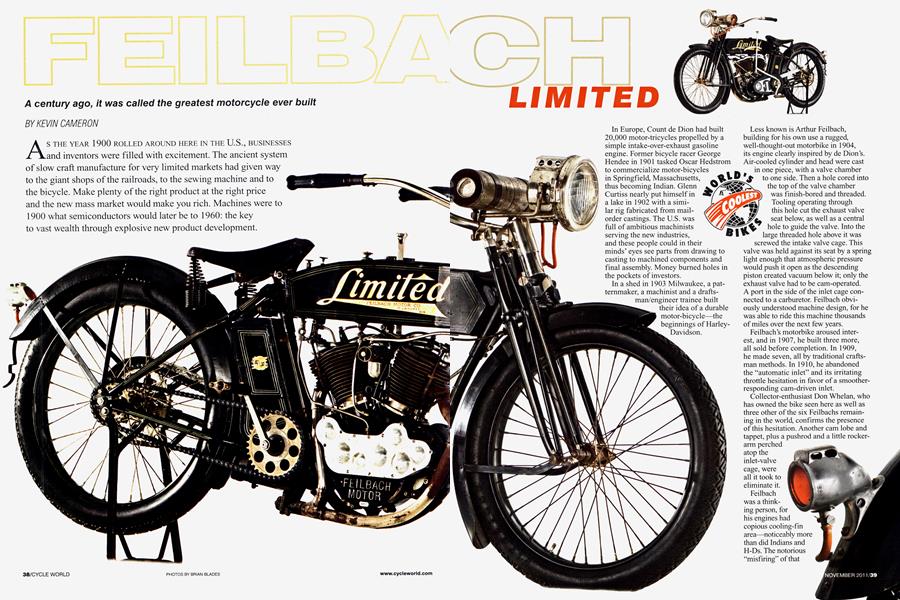

FEILBACH LIMITED

A century ago, it was called the greatest motorcycle ever built

KEVIN CAMERON

AS THE YEAR 1900 ROLLED AROUND HERE IN THE U.S., BUSINESSES and inventors were filled with excitement. The ancient system of slow craft manufacture for very limited markets had given way to the giant shops of the railroads, to the sewing machine and to the bicycle. Make plenty of the right product at the right price and the new mass market would make you rich. Machines were to 1900 what semiconductors would later be to 1960: the key to vast wealth through explosive new product development.

In Europe, Count de Dion had built 20,000 motor-tricycles propelled by a simple intake-over-exhaust gasoline engine. Former bicycle racer George Hendee in 1901 tasked Oscar Hedstrom to commercialize motor-bicycles in Springfield, Massachusetts, thus becoming Indian. Glenn Curtiss nearly put himself in a lake in 1902 with a similar rig fabricated from mailorder castings. The U.S. was full of ambitious machinists serving the new industries, and these people could in their minds’ eyes see parts from drawing to casting to machined components and final assembly. Money burned holes in the pockets of investors.

In a shed in 1903 Milwaukee, a patternmaker, a machinist and a draftsman/engineer trainee built

their idea of a durable motor-bicycle—the beginnings of HarleyDavidson.

Less known is Arthur Feilbach, building for his own use a rugged, well-thought-out motorbike in 1904, its engine clearly inspired by de Dion’s. Air-cooled cylinder and head were cast in one piece, with a valve chamber to one side. Then a hole cored into the top of the valve chamber was finish-bored and threaded. Tooling operating through this hole cut the exhaust valve seat below, as well as a central hole to guide the valve. Into the large threaded hole above it was screwed the intake valve cage. This valve was held against its seat by a spring light enough that atmospheric pressure would push it open as the descending piston created vacuum below it; only the exhaust valve had to be cam-operated. A port in the side of the inlet cage connected to a carburetor. Feilbach obviously understood machine design, for he was able to ride this machine thousands of miles over the next few years.

Feilbach's motorbike aroused inter est, and in 1907, he built three more, all sold before completion. In 1909, he made seven, all by traditional crafts man methods. In 1910, he abandoned the "automatic inlet" and its irritating throttle hesitation in favor of a smoother responding cam-driven inlet.

Collector-enthusiast Don Whelan, who has owned the bike seen here as well as three other of the six Feilbachs remaining in the world, confirms the presence of this hesitation. Another cam lobe and tappet, plus a pushrod and a little rockerarm perched atop the inlet-valve cage, were all it took to eliminate it.

Feilbach was a thinking person, for his engines had copious cooling-fin area—noticeably more than did Indians and H-Ds. The notorious “misfiring” of that era’s engines, which sometimes became so hot in operation that the charge was fired by the glowing iron piston or head. Not for him.

In 1911, he designed the “Feilbach Limited” Twin pictured here, with a 35/i6-by-4-inch bore and stroke giving a generous displacement of 69 cubic inches, or nearly 1130cc. It would hit the market in 1913.

Harley had been selling its 1 909-de signed 50-cubic-inch V-Twins to the Milwaukee police, but the new Feilbach was something else. Its 40-percentbigger displacement and muscular torque easily powered it up Milwaukee's steep 19th Street hill, and it could overhaul any speeder's car. City police took notice and began to buy Feilbachs. In 1913, 108 Twins and 50 Singles were built. Feilbach moved into a larger, 7100-square-foot building, with tooling (and, presumably, finance) in place for serious production. Things were looking up!

How could anyone have known that 1913 would be the peak year for industry leader Indian, who built 32,000 bikes? Henry Ford was perfecting a production scheme that would cut the assembly time for a car from 750 hours by a single craftsman to 93 minutes for his fast-developing concept, the production line. Cheap, rugged Ford cars stunted U.S. motorcycling. Who but the young and adventurous would pay $290 for a motorcycle when Henry’s Model T was barely over $300?

Yet in 1914, Feilbach produced nearly 1000 machines, so people clearly wanted them. With hindsight, this was a race to become big enough to survive the Model T, to become big enough, tightly enough tied into the market, to survive mostly on the sporting buyer and police orders.

England had no Henry Ford, so its history was very different. There, the motorcycle remained the cheapest of motorized transportation. This was the basis of the motorcycle’s English golden age, the 1920s, when motorcycle and sidecar registrations outnumbered those of cars. Here in the U.S., the car took the mass market.

On the Limited big Twin in these photographs, the timing chest on the right drives a pair of two-lobed cams, one ahead of the front cylinder, the other behind the rear. One lobe operates the exhaust valve, its stem downward as in a flathead engine. The other operates the pushrod, which is joggled to clear the large cylinder finning on its way to the intake rocker above the head. A graceful polished aluminum casting performs the functions of both intake-valve cages and intake manifold. Sparkplugs are centered over the cylinder bores, served by a magneto ahead of the front cylinder. A 2-into-l exhaust system is routed to a muffler under the toolbox or, by cutout valve, straight to atmosphere. Great sound, on demand, without the aftermarket.

Scan for more photos

cycleworld.com/feilbach

The chassis is rigid and strongly constructed. The fork is of the “Castle” or Harley pattern, lubricated at its pivots by oil cups. The large tank across the handlebar is the acetylene generator, supplying the gas to taillight and headlight through copper and flexible tubing. The cylinders are base-bolted to the aluminum crankcase—plenty strong for this engine’s claimed 10 horsepower.

Traditional starting was by pedaling off vigorously with the exhaust lifter pulled in, then releasing it. But Feilbach advertising states that the engine may be started off the stand, requiring a clutch to turn the pedals into a kickstarter. An optional two-speed planetary gearbox made the machine attractive for sidecar use (to heave the extra weight into motion).

An oil line runs from the rear of the tankage to the top of the timing chest, and brochures claimed that pumpless oiling (by total loss) was always proportional to engine speed. Motorcycling had to wait until the mid-1920s for pumped, recirculating oil systems.

What stopped Feilbach? With a promising 900-1000 modern machines sold in 1914, why did production cease forever late that year? The Feilbach family says that Harley-Davidson wanted no competitors, arranging their demise much as Detroit made it tough for 1947 newcomer Henry J. Kaiser. For some reason, that great wartime industrialist who streamlined the production of Liberty Ships just couldn’t get the industry price for generators, starters and coiled steel sheet. A mystery of business, which has its dark side.

When the owner of this bike (it sold last time for nearly a quarter-mil) looked into the cylinders, he saw it had never been run. It is a nearly 100-yearold time capsule, a look back at an era of rapid industrial expansion, glittering opportunity and irresistible ratios of risk to reward. It still looks good to us today.

A company brochure assures us that, “When you see the ‘Limited’ go up the 19th St. hill you’ll know why every rider says it’s the greatest motorcycle ever produced.”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Columns

ColumnsUp Front

November 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

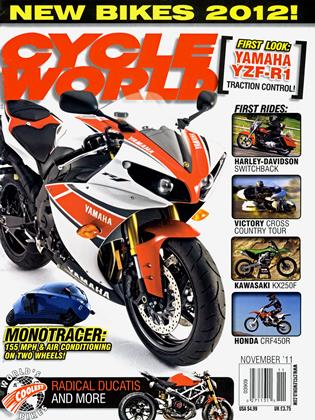

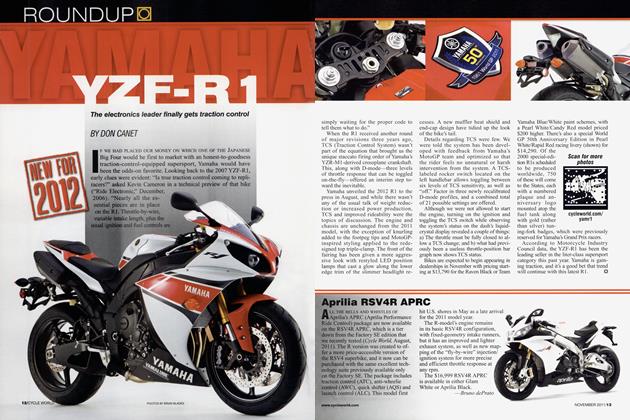

RoundupYamaha Yzf-R1

November 2011 By Don Canet -

Roundup

RoundupThe Future of Mx?

November 2011 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupMission Accomplished: Rapp Wins At Laguna

November 2011 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupFonzie's Triumph To Auction

November 2011 By Robert Stokstad -

25 Years Ago November 1986

November 2011 By Don Canet