Battle of the Dust

UP FRONT

MARK HOYER

SOMETIMES THE PAIN IS TOO MUCH.

Sometimes, when you’ve been so horribly wronged, you just can’t look under the Shroud of Death, the place where you’ve hidden the hurt.

But it was time to go to that dark corner of the garage and pull the dusty bed sheet off the Velocette.

Since you haven’t been trying to forget, like I have, perhaps you’ll remember “The Last Rebuild” column I wrote (Up Front, February) about the trials of keeping my 1954 MSS 500cc Single on the road as a traveling bike and commuter. And all the things I keep having to do to it when it is off the road.

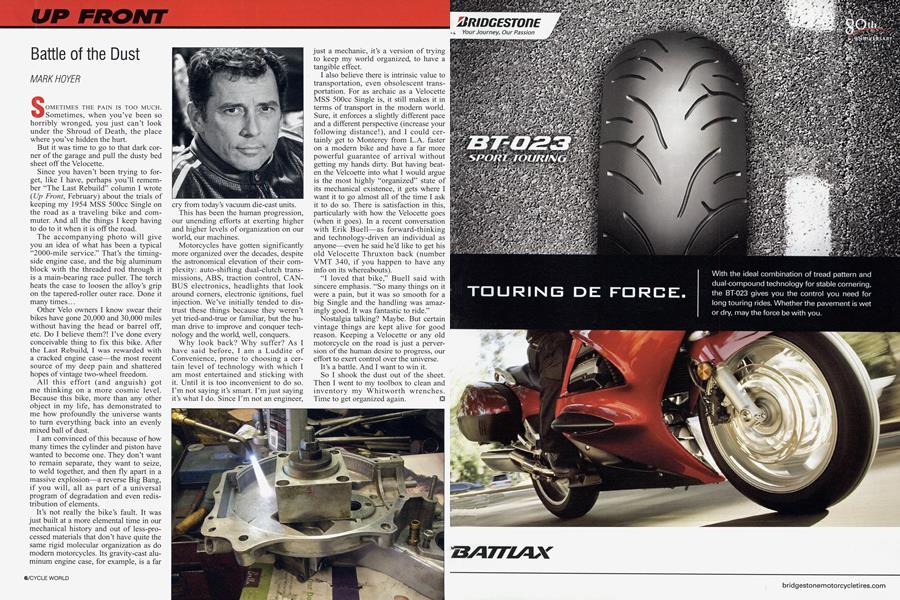

The accompanying photo will give you an idea of what has been a typical “2000-mile service.” That’s the timingside engine case, and the big aluminum block with the threaded rod through it is a main-bearing race puller. The torch heats the case to loosen the alloy’s grip on the tapered-roller outer race. Done it many times...

Other Velo owners I know swear their bikes have gone 20,000 and 30,000 miles without having the head or barrel off, etc. Do I believe them?! I’ve done every conceivable thing to fix this bike. After the Last Rebuild, I was rewarded with a cracked engine case—the most recent source of my deep pain and shattered hopes of vintage two-wheel freedom.

All this effort (and anguish) got me thinking on a more cosmic level. Because this bike, more than any other object in my life, has demonstrated to me how profoundly the universe wants to turn everything back into an evenly mixed ball of dust.

I am convinced of this because of how many times the cylinder and piston have wanted to become one. They don’t want to remain separate, they want to seize, to weld together, and then fly apart in a massive explosion—a reverse Big Bang, if you will, all as part of a universal program of degradation and even redistribution of elements.

It’s not really the bike’s fault. It was just built at a more elemental time in our mechanical history and out of less-processed materials that don’t have quite the same rigid molecular organization as do modem motorcycles. Its gravity-cast aluminum engine case, for example, is a far

cry from today’s vacuum die-cast units.

This has been the human progression, our unending efforts at exerting higher and higher levels of organization on our world, our machines.

Motorcycles have gotten significantly more organized over the decades, despite the astronomical elevation of their complexity: auto-shifting dual-clutch transmissions, ABS, traction control, CANBUS electronics, headlights that look around comers, electronic ignitions, fuel injection. We’ve initially tended to distrust these things because they weren’t yet tried-and-true or familiar, but the human drive to improve and conquer technology and the world, well, conquers.

Why look back? Why suffer? As I have said before, I am a Luddite of Convenience, prone to choosing a certain level of technology with which I am most entertained and sticking with it. Until it is too inconvenient to do so. I’m not saying it’s smart. I’m just saying it’s what I do. Since I’m not an engineer,

just a mechanic, it’s a version of trying to keep my world organized, to have a tangible effect.

I also believe there is intrinsic value to transportation, even obsolescent transportation. For as archaic as a Velocette MSS 500cc Single is, it still makes it in terms of transport in the modem world. Sure, it enforces a slightly different pace and a different perspective (increase your following distance!), and I could certainly get to Monterey from L.A. faster on a modern bike and have a far more powerful guarantee of arrival without getting my hands dirty. But having beaten the Velcoette into what I would argue is the most highly “organized” state of its mechanical existence, it gets where I want it to go almost all of the time I ask it to do so. There is satisfaction in this, particularly with how the Velocette goes (when it goes). In a recent conversation with Erik Buell—as forward-thinking and technology-driven an individual as anyone—even he said he’d like to get his old Velocette Thruxton back (number VMT 340, if you happen to have any info on its whereabouts).

“I loved that bike,” Buell said with sincere emphasis. “So many things on it were a pain, but it was so smooth for a big Single and the handling was amazingly good. It was fantastic to ride.”

Nostalgia talking? Maybe. But certain vintage things are kept alive for good reason. Keeping a Velocette or any old motorcycle on the road is just a perversion of the human desire to progress, our effort to exert control over the universe.

It’s a battle. And I want to win it.

So I shook the dust out of the sheet. Then I went to my toolbox to clean and inventory my Whitworth wrenches. Time to get organized again. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Roundup

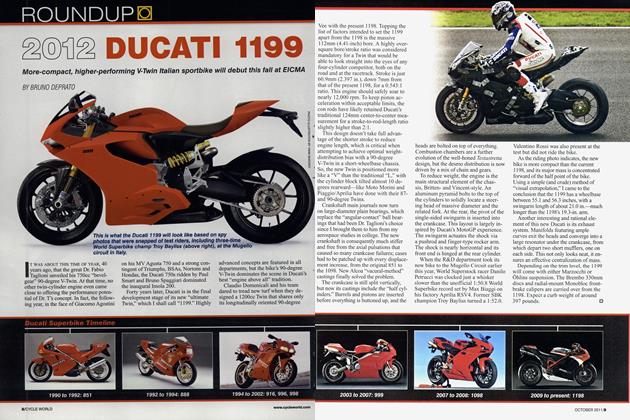

Roundup2012 Ducati 1199

OCTOBER 2011 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

RoundupHonda's Nsf250r Moto3 Contender

OCTOBER 2011 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

Roundup2012 Mv Agusta F3 Serie Oro

OCTOBER 2011 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago October 1986

OCTOBER 2011 By Paul Dean -

Roundup

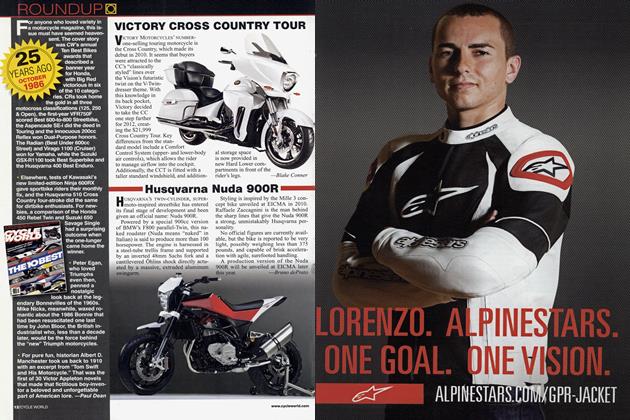

RoundupVictory Cross Country Tour

OCTOBER 2011 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

RoundupHusqvarna Nuda 900r

OCTOBER 2011 By Bruno Deprato