UP FRONT

The “Last” Rebuild

MARK HOYER

MAYBE IT’S WHAT I GET FOR MOUTHing off a couple of months ago. Just about the time I finished pondering the Price of Sanity and went on record about using vintage stuff as real transportation, lightning cracked down from the heavens in a strange horizontal bolt.

Not that I should be, ahem, shocked. But sometimes old stuff is just old.

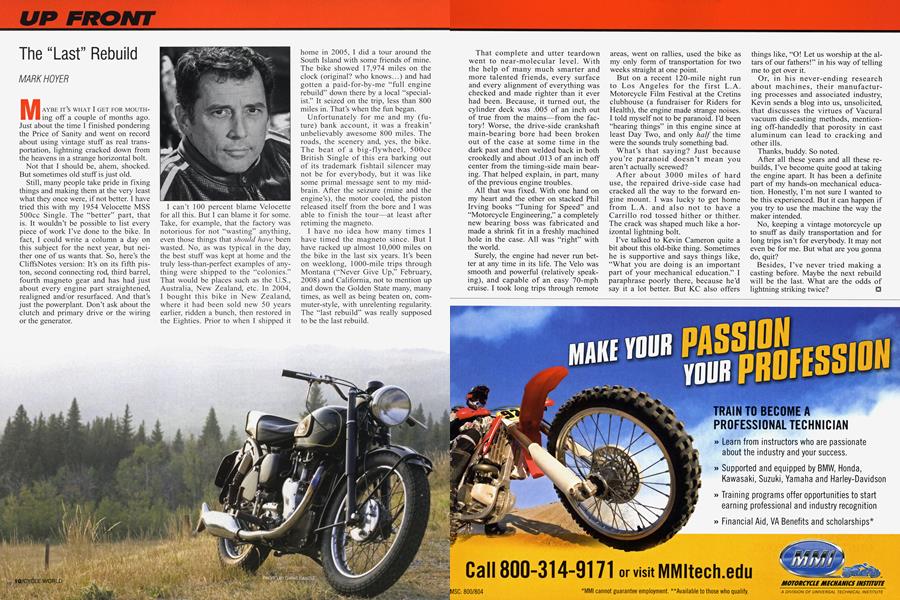

Still, many people take pride in fixing things and making them at the very least what they once were, if not better. I have tried this with my 1954 Velocette MSS 500cc Single. The “better” part, that is. It wouldn’t be possible to list every piece of work I’ve done to the bike. In fact, I could write a column a day on this subject for the next year, but neither one of us wants that. So, here’s the CliffsNotes version: It’s on its fifth piston, second connecting rod, third barrel, fourth magneto gear and has had just about every engine part straightened, realigned and/or resurfaced. And that’s just the powerplant. Don’t ask about the clutch and primary drive or the wiring or the generator.

I can’t 100 percent blame Velocette for all this. But I can blame it for some. Take, for example, that the factory was notorious for not “wasting” anything, even those things that should have been wasted. No, as was typical in the day, the best stuff was kept at home and the truly less-than-perfect examples of anything were shipped to the “colonies.” That would be places such as the U.S., Australia, New Zealand, etc. In 2004, I bought this bike in New Zealand, where it had been sold new 50 years earlier, ridden a bunch, then restored in the Eighties. Prior to when I shipped it home in 2005, I did a tour around the South Island with some friends of mine. The bike showed 17,974 miles on the clock (original? who knows...) and had gotten a paid-for-by-me “full engine rebuild” down there by a local “specialist.” It seized on the trip, less than 800 miles in. That’s when the fun began.

Unfortunately for me and my (future) bank account, it was a freakin’ unbelievably awesome 800 miles. The roads, the scenery and, yes, the bike. The beat of a big-flywheel, 500cc British Single of this era barking out of its trademark fishtail silencer may not be for everybody, but it was like some primal message sent to my midbrain. After the seizure (mine and the engine’s), the motor cooled, the piston released itself from the bore and I was able to finish the tour—at least after retiming the magneto.

I have no idea how many times I have timed the magneto since. But I have racked up almost 10,000 miles on the bike in the last six years. It’s been on weeklong, 1000-mile trips through Montana (“Never Give Up,” February, 2008) and California, not to mention up and down the Golden State many, many times, as well as being beaten on, commuter-style, with unrelenting regularity. The “last rebuild” was really supposed to be the last rebuild.

That complete and utter teardown went to near-molecular level. With the help of many much smarter and more talented friends, every surface and every alignment of everything was checked and made righter than it ever had been. Because, it turned out, the cylinder deck was .005 of an inch out of true from the mains—from the factory! Worse, the drive-side crankshaft main-bearing bore had been broken out of the case at some time in the dark past and then welded back in both crookedly and about .013 of an inch off center from the timing-side main bearing. That helped explain, in part, many of the previous engine troubles.

All that was fixed. With one hand on my heart and the other on stacked Phil Irving books “Tuning for Speed” and “Motorcycle Engineering,” a completely new bearing boss was fabricated and made a shrink fit in a freshly machined hole in the case. All was “right” with the world.

Surely, the engine had never run better at any time in its life. The Velo was smooth and powerful (relatively speaking), and capable of an easy 70-mph cruise. I took long trips through remote

areas, went on rallies, used the bike as my only form of transportation for two weeks straight at one point.

But on a recent 120-mile night run to Los Angeles for the first L.A. Motorcycle Film Festival at the Cretins clubhouse (a fundraiser for Riders for Health), the engine made strange noises. I told myself not to be paranoid. I’d been “hearing things” in this engine since at least Day Two, and only half the time were the sounds truly something bad.

What’s that saying? Just because you’re paranoid doesn’t mean you aren’t actually screwed?

After about 3000 miles of hard use, the repaired drive-side case had cracked all the way to the forward engine mount. I was lucky to get home from L.A. and also not to have a Carrillo rod tossed hither or thither. The crack was shaped much like a horizontal lightning bolt.

I’ve talked to Kevin Cameron quite a bit about this old-bike thing. Sometimes he is supportive and says things like, “What you are doing is an important part of your mechanical education.” I paraphrase poorly there, because he’d say it a lot better. But KC also offers

things like, “O! Let us worship at the altars of our fathers!” in his way of telling me to get over it.

Or, in his never-ending research about machines, their manufacturing processes and associated industry, Kevin sends a blog into us, unsolicited, that discusses the virtues of Vacural vacuum die-casting methods, mentioning off-handedly that porosity in cast aluminum can lead to cracking and other ills.

Thanks, buddy. So noted.

After all these years and all these rebuilds, I’ve become quite good at taking the engine apart. It has been a definite part of my hands-on mechanical education. Honestly, I’m not sure I wanted to be this experienced. But it can happen if you try to use the machine the way the maker intended.

No, keeping a vintage motorcycle up to snuff as daily transportation and for long trips isn’t for everybody. It may not even be for me. But what are you gonna do, quit?

Besides, I’ve never tried making a casting before. Maybe the next rebuild will be the last. What are the odds of lightning striking twice? □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Roundup

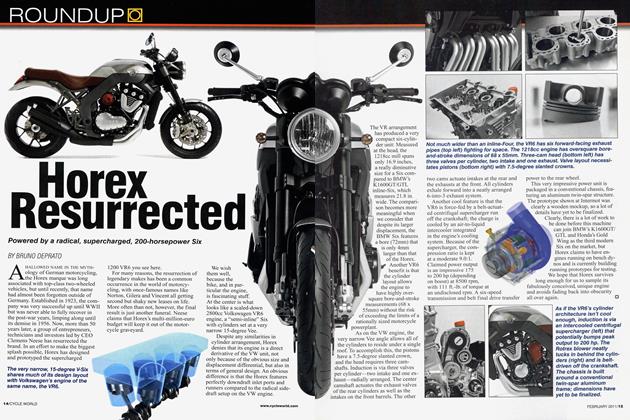

RoundupHorex Resurrected

FEBRUARY 2011 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

Roundup2012 Ducati Superbike

FEBRUARY 2011 By Jeff Roberts -

Roundup

RoundupLittle Hauler

FEBRUARY 2011 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago September 1985

FEBRUARY 2011 By John Burns -

Roundup

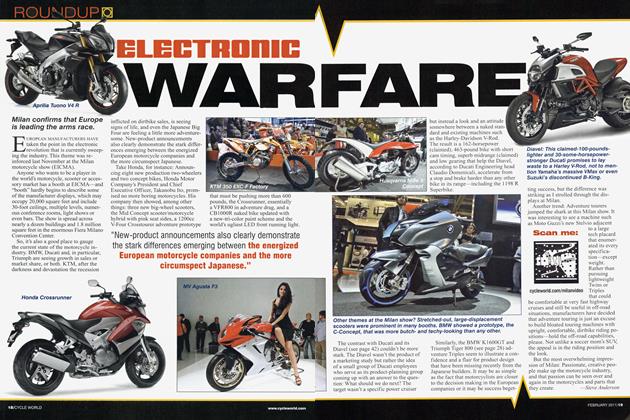

RoundupElectronic War Fare

FEBRUARY 2011 By Steve Anderson -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

FEBRUARY 2011