Small Change

LEANINGS

PETER EGAN

IT MAY BE TRUE THAT THE FLUTTERING of a butterfly wing in the Amazon changes the weather in Des Moines, but nothing has more consequential echoes than the changing of a single part on a motorcycle.

Swap your handlebars—as I did for a more traditional Sixties’ bend on my Triumph Scrambler last week—and the ramifications proliferate. The bar-end weights on the stock bike have their anchors either pressed or glued in (I can’t get them out, at any rate), so now I need a new set of weights or else new grips to cover the unsightly holes on the ends of the bars.

No big deal, but I have to find the parts or order them, and the job’s not quite done at this moment. Also, the new bars keep the brake master from rotating into exactly the right position for my right hand, so I’ve moved the bars just a little higher to compensate. And on the left side, I naturally drilled one wrong “experimental” hole in the handlebars before I got the left switch cluster peg to index properly on the bars. I’m sure no one will ever see it— unless the left grip snaps off in a corner and kills me.

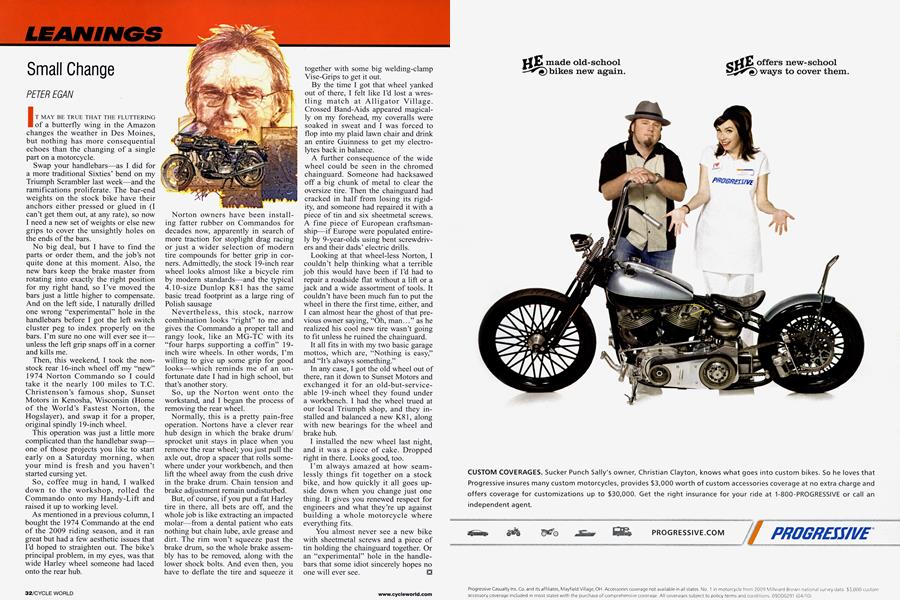

Then, this weekend, I took the nonstock rear 16-inch wheel off my “new” 1974 Norton Commando so I could take it the nearly 100 miles to T.C. Christenson’s famous shop, Sunset Motors in Kenosha, Wisconsin (Home of the World’s Fastest Norton, the Hogslayer), and swap it for a proper, original spindly 19-inch wheel.

This operation was just a little more complicated than the handlebar swap— one of those projects you like to start early on a Saturday morning, when your mind is fresh and you haven’t started cursing yet.

So, coffee mug in hand, I walked down to the workshop, rolled the Commando onto my Handy-Lift and raised it up to working level.

As mentioned in a previous column, I bought the 1974 Commando at the end of the 2009 riding season, and it ran great but had a few aesthetic issues that I’d hoped to straighten out. The bike’s principal problem, in my eyes, was that wide Harley wheel someone had laced onto the rear hub.

Norton owners have been installing fatter rubber on Commandos for decades now, apparently in search of more traction for stoplight drag racing or just a wider selection of modern tire compounds for better grip in corners. Admittedly, the stock 19-inch rear wheel looks almost like a bicycle rim by modern standards—and the typical 4.10-size Dunlop K81 has the same basic tread footprint as a large ring of Polish sausage

Nevertheless, this stock, narrow combination looks “right” to me and gives the Commando a proper tall and rangy look, like an MG-TC with its “four harps supporting a coffin” 19inch wire wheels. In other words, I’m willing to give up some grip for good looks—which reminds me of an unfortunate date I had in high school, but that’s another story.

So, up the Norton went onto the workstand, and I began the process of removing the rear wheel.

Normally, this is a pretty pain-free operation. Nortons have a clever rear hub design in which the brake drum/ sprocket unit stays in place when you remove the rear wheel; you just pull the axle out, drop a spacer that rolls somewhere under your workbench, and then lift the wheel away from the cush drive in the brake drum. Chain tension and brake adjustment remain undisturbed.

But, of course, if you put a fat Harley tire in there, all bets are off, and the whole job is like extracting an impacted molar—from a dental patient who eats nothing but chain lube, axle grease and dirt. The rim won’t squeeze past the brake drum, so the whole brake assembly has to be removed, along with the lower shock bolts. And even then, you have to deflate the tire and squeeze it

together with some big welding-clamp Vise-Grips to get it out.

By the time I got that wheel yanked out of there, I felt like I’d lost a wrestling match at Alligator Village. Crossed Band-Aids appeared magically on my forehead, my coveralls were soaked in sweat and I was forced to flop into my plaid lawn chair and drink an entire Guinness to get my electrolytes back in balance.

A further consequence of the wide wheel could be seen in the chromed chainguard. Someone had hacksawed off a big chunk of metal to clear the oversize tire. Then the chainguard had cracked in half from losing its rigidity, and someone had repaired it with a piece of tin and six sheetmetal screws. A fine piece of European craftsmanship—if Europe were populated entirely by 9-year-olds using bent screwdrivers and their dads’ electric drills.

Looking at that wheel-less Norton, I couldn’t help thinking what a terrible job this would have been if I’d had to repair a roadside flat without a lift or a jack and a wide assortment of tools. It couldn’t have been much fun to put the wheel in there the first time, either, and I can almost hear the ghost of that previous owner saying, “Oh, man...” as he realized his cool new tire wasn’t going to fit unless he ruined the chainguard.

It all fits in with my two basic garage mottos, which are, “Nothing is easy,” and “It’s always something.”

In any case, I got the old wheel out of there, ran it down to Sunset Motors and exchanged it for an old-but-serviceable 19-inch wheel they found under a workbench. I had the wheel trued at our local Triumph shop, and they installed and balanced a new K81, along with new bearings for the wheel and brake hub.

I installed the new wheel last night, and it was a piece of cake. Dropped right in there. Looks good, too.

I’m always amazed at how seamlessly things fit together on a stock bike, and how quickly it all goes upside down when you change just one thing. It gives you renewed respect for engineers and what they’re up against building a whole motorcycle where everything fits.

You almost never see a new bike with sheetmetal screws and a piece of tin holding the chainguard together. Or an “experimental” hole in the handlebars that some idiot sincerely hopes no one will ever see.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontRisk Management

JULY 2010 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupThrottle By Wire

JULY 2010 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupTeam Cycle World

JULY 2010 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupWill the Real F4 Please Stand Up?

JULY 2010 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

RoundupMiddleweight Eight!

JULY 2010 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago July 1985

JULY 2010 By Blake Conner