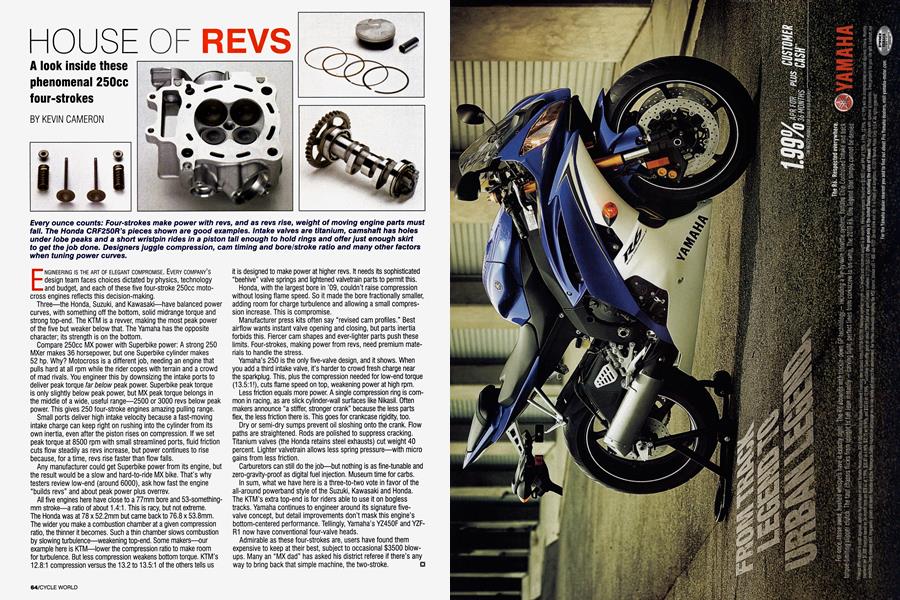

HOUSE OF REVS

A look inside these phenomenal 250cc four-strokes

KEVIN CAMERON

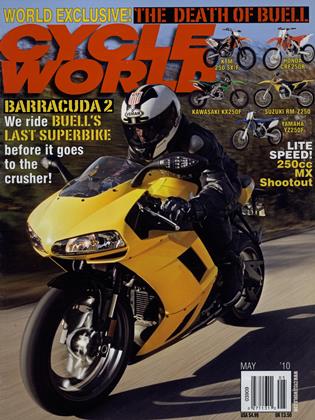

ENGINEERING IS THE ART OF ELEGANT COMPROMISE. EVERY COMPANY'S design team faces choices dictated by physics, technology and budget, and each of these five four-stroke 250cc motocross engines reflects this decision-making.

Three—the Honda, Suzuki, and Kawasaki—have balanced power curves, with something off the bottom, solid midrange torque and strong top-end. The KTM is a revver, making the most peak power of the five but weaker below that. The Yamaha has the opposite character; its strength is on the bottom.

Compare 250cc MX power with Superbike power: A strong 250 MXer makes 36 horsepower, but one Superbike cylinder makes 52 hp. Why? Motocross is a different job, needing an engine that pulls hard at all rpm while the rider copes with terrain and a crowd of mad rivals. You engineer this by downsizing the intake ports to deliver peak torque far below peak power. Superbike peak torque is only slightly below peak power, but MX peak torque belongs in the middle of a wide, useful range-2500 or 3000 revs below peak power. This gives 250 four-stroke engines amazing pulling range.

Small ports deliver high intake velocity because a fast-moving intake charge can keep right on rushing into the cylinder from its own inertia, even after the piston rises on compression. If we set peak torque at 8500 rpm with small streamlined ports, fluid friction cuts flow steadily as revs increase, but power continues to rise because, for a time, revs rise faster than flow falls.

Any manufacturer could get Superbike power from its engine, but the result would be a slow and hard-to-ride MX bike. That's why testers review low-end (around 6000), ask how fast the engine "builds revs" and about peak power plus overrev.

All five engines here have close to a 77mm bore and 53-somethingmm stroke-a ratio of about 1.4:1. This is racy, but not extreme. The Honda was at 78 x 52.2mm but came back to 76.8 x 53.8mm. The wider you make a combustion chamber at a given compression ratio, the thinner becomes. Such a thin chamber slows combustion by slowing turbulence-weakening top-end. Some makers-our example here is KTM-lower the compression ratio to make room for turbulence. But less compression weakens bottom torque. KTM's 12.8:1 compression versus the 13.2 to 13.5:1 of the others tells us

is designed to make power at higher revs. It needs s sophisticated "beehive" valve sp~ngs and lightened valvetrain parts to permit this. Honda, with the largest bore in `09, couldn't raise compression without losing flame speed. So it made the bore fractionally smaller, adding room for charge turbulence and allowing a small compres sion increase. This is compromise.

Manufacturer press kits often say "revised cam profiles." Best airflow wants instant valve opening and closing, but parts inertia forbids this. Fiercer cam shapes and ever-lighter parts push these limits. Four-strokes, making power from revs, need premium mate rials to handle the stress.

Yamaha's 250 is the only five-valve design, and it shows. When you add a third intake valve, it's harder to crowd fresh charge near the sparkplug. This, plus the compression needed for low-end torque (13.5:1!), cuts flame speed on top, weakening power at high rpm.

Less ifiction equals more power. A single compression ng is com mon in racing, as are slick cylinder-wall surfaces like Nikasil. Often makers announce "a stiffer, stronger crank" because the less parts flex, the less ifiction there is. This goes for crankcase gidity, too.

Dry or semi-dry sumps prevent oil sloshing onto the crank. Flow paths are straightened. Rods are polished to suppress cracking. Titanium valves (the Honda retains steel exhausts) cut weight 40 percent. Lighter valvetrain allows less spring pressure-with micro gains from less friction.

Carburetors can still do the job-but nothing is as fine-tunable and zero-gravity-proof as digital fuel injection. Museum time for carbs.

In sum, what we have here is a three-to-two vote in favor of the all-around powerband style of the Suzuki, Kawasaki and Honda. The KTM's extra top-end is for riders able to use it on bogless tracks. Yamaha continues to engineer around its signature fivevalve concept, but detail improvements don't mask this engine's bottom-centered performance. Tellingly, Yamaha's YZ45OF and YZF Ri now have conventional four-valve heads.

Admirable as these four-strokes are, users have found them expensive to keep at their best, subject to occasional $3500 blow ups. Many an "MX dad" has asked his district referee if there's any way to bring back that simple machine, the two-stroke.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontGreat Books

May 2010 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

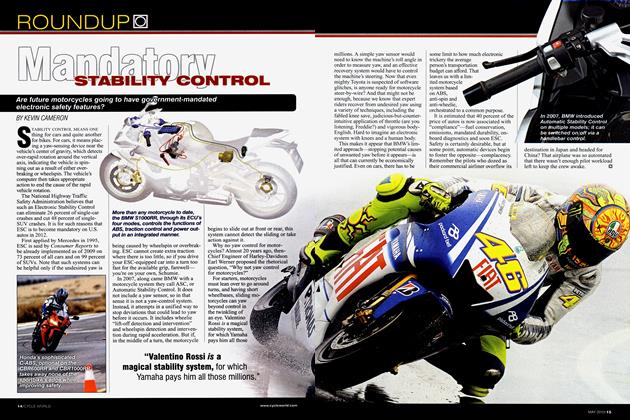

RoundupMandatory Stability Control

May 2010 By Kevin Cameron -

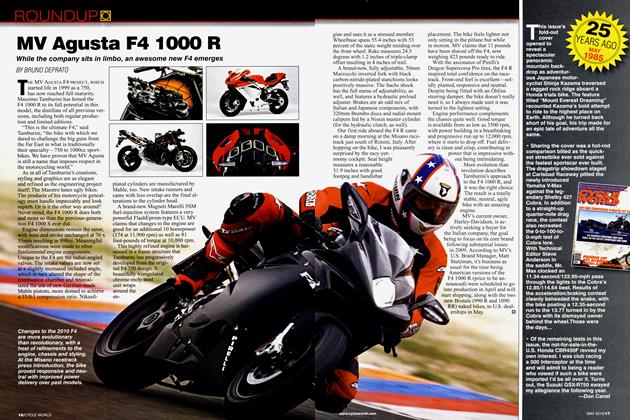

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago May 1985

May 2010 By Don Canet -

Roundup

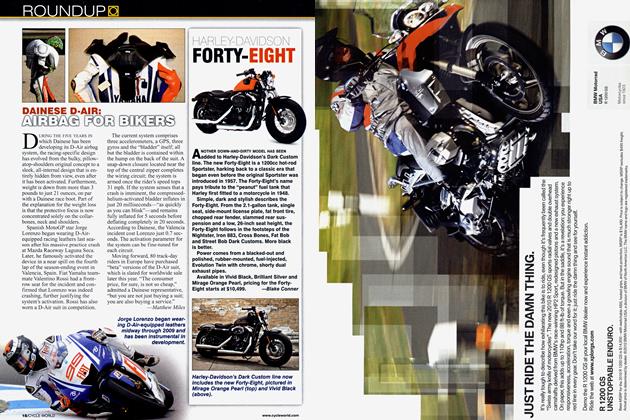

RoundupDainese D-Air: Airbag For Bikers

May 2010 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupPitch, Putt And Peruse

May 2010 By Robert Stokstad -

Roundup

RoundupUps & Downs

May 2010