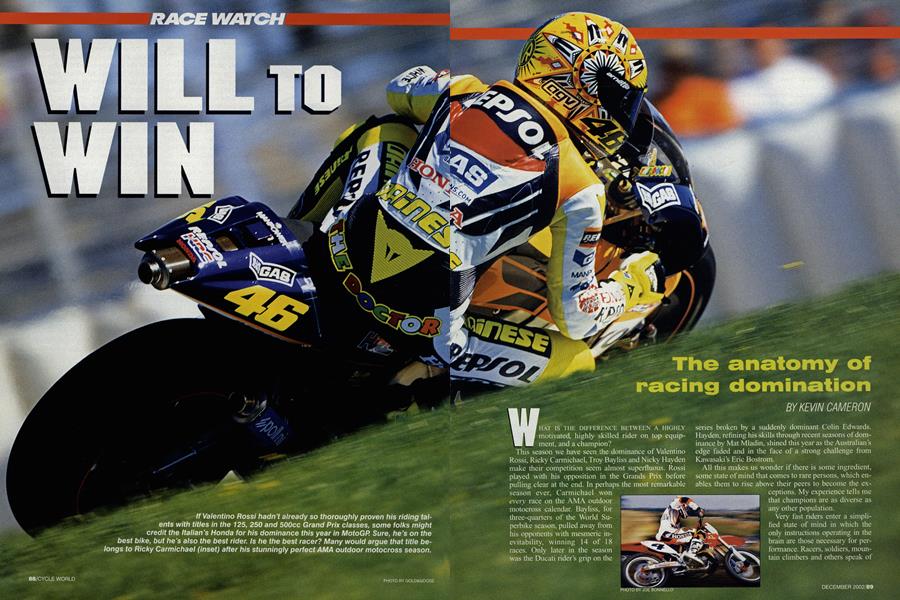

WILL TO WIN

RACE WATCH

The anatomy of racing domination

KEVIN CAMERON

WHAT IS THE DIFFERENCE BETWEEN A HIGHLY motivated, highly skilled rider on top equipment, and a champion?

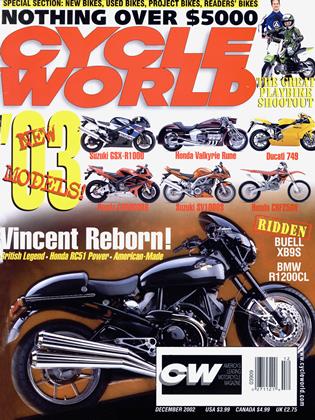

This season we have seen the dominance of Valentino Rossi, Ricky Carmichael, Troy Bayliss and Nicky Hayden make their competition seem almost superfluous. Rossi played with his opposition in the Grands Prix before pulling clear at the end. In perhaps the most remarkable season ever, Carmichael won every race on the AMA outdoor motocross calendar. Bayliss, for three-quarters of the World Superbike season, pulled away from his opponents with mesmeric inevitability, winning 14 of 18 races. Only later in the season was the Ducati rider’s grip on the series broken by a suddenly dominant Colin Edwards. Hayden, refining his skills through recent seasons of dominance by Mat Mladin, shined this year as the Australian’s edge faded and in the face of a strong challenge from Kawasaki’s Eric Bostrom.

All this makes us wonder if there is some ingredient, some state of mind that comes to rare persons, which enables them to rise above their peers to become the exMy experience tells me tjlat cjlampjons are as diverse as any other population.

Very fast riders enter a simplified state of mind in which the only instructions operating in the brain are those necessary for performalice. Racers, soldiers, mountain climbers and others speak of this special state of mind in which they can see everything, can anticipate what will happen and perceive their tasks in simple, diagrammatic form. This is a very rewarding condition, a state of perfection in which mistakes seem impossible, perceptions infallible. When I asked three-time 500cc World Champion Kenny Roberts Sr. about this, he replied, “That’s something I don’t talk about.” Four-time AMA Formula One Champion Mike Baldwin described the transition from normal mental process into this accelerated state. “When you get to Daytona for the first test of the year, the team’s all lined up along the pit wall. There is the big transporter. Everybody’s expecting you to go fast on the new bike. I go around a couple of times. When I approach the chicane, I know I normally go in to the last board before braking, and now I try to do it. But I can look down and see my hand turning the throttle back, going for the brake-without my even willing it. I can’t make myself go in there. The pressure builds up-I know everybody’s got a stopwatch, they’re expecting to see something happen, but I’m going slow.

“Finally, I’m desperate. I force myself to go in to the last board at the chicane, and it’s scaring me so bad, things are happening too fast to think, the bike slams to the left, then right and left and I’m out of there, wondering how I’m still in one piece. And then the next time I go in there, it’s as though everything’s slowed way down. I can see all the ripples in the pavement and I can feel the tires going over them as I brake. I push on the bars and the bike slowly leans in, and I can feel everything the tires are doing. Everything’s in slow motion and I’m able to handle everything. And it stays like that for the rest of the season.”

Other riders report a similar accelerated mental process that moves ahead of events. Roberts refines this further, relating that depending on other variables, he might even be too far ahead of the bike.

Even this is only part of the picture. Less successful racers enter this state but can’t control it. They may go faster and faster until they crash or they may, despite their obvious intelligence, display poor judgment-there are highly respected riders whose brilliance exceeds their accomplishments in titles won. The depth of this state is seen in the crashed riders who fight off attempts to help them. Their minds are still racing. Or a fast rider may decide consciously to rein himself in. In 1977, the late Dale Singleton proved to himself that he could ride at top level, but he felt out of his depth and moderated his style. When I asked him about this, he replied, “I’m just gittin’ the money, Kevin.” He had decided to go as far as he could at a risk level he found manageable.

One of the most disciplined was fourtime 500cc World Champion Eddie Lawson. In early race laps, he would decide if he could win or should settle for less. Risk management wins championships. Falling in a glorious attempt at the impossible earns no points.

It helps mentally to have an edge. As racer/engineer Albert Gunter once told a young Dick Mann, “Don’t try to beat people with their own methods-they’ve had them longer than you. Find your own way, something nobody else has.”

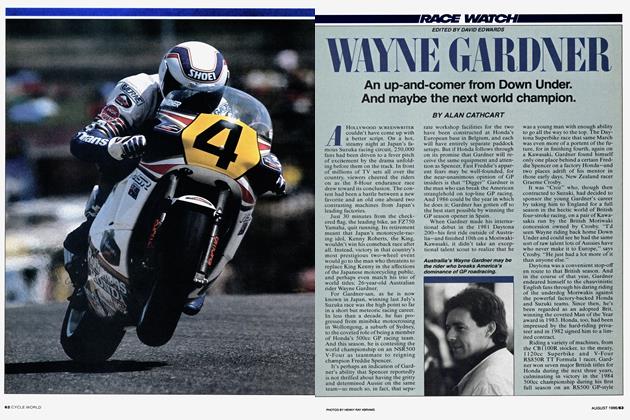

New riding techniques develop because motorcycles and tires evolve faster than most riders’ styles. Whoever first exploits these developments has an edge. Roberts reached the top in the U.S. just as high-powered two-stroke roadracers emerged. Because these bikes accelerated so hard, the center of gravity was moved forward to make them steer off comers instead of lifting the front and running wide. These bikes weren’t light, so entering comers while decelerating put excess load on small front tires, making front grip touchy. Kenny’s dirt-track style of steering with the throttle suited this new, dragster-style bike because these big 750cc strokers were more stable when accelerating (weight on the large rear tire) than when braking or coasting (weight on the undersized front tire). Kenny entered comers at less than ultimate apex speed, got the bike turned, then used the remaining corner as a curved dragstrip from which to launch hard. Let other riders win the apex-Kenny won the comers and the straights that followed.

Three-time World Champion Freddie Spencer took it further. He entered corners at such a high speed that a normal technique would have pushed the front tire loose as the bike reached full lean. Before this could happen, Spencer stopped the excess forward weight transfer with a touch of throttle. That is why in certain corners, you would hear the throttle come in at the very instant his bike reached full lean. In his first 500cc championship year, 1983, even experienced observers believed his underpowered three-cylinder Honda had terrific bottom-end acceleration, but what they were seeing was corner speed, made possible by using the throttle to trim front/rear tire loads.

Lawson was responding to this same situation when he said, in 1984, “I’m not sure how it works, but your lap times really start to come down when you quit just rolling in to the apex and crack the throttle instead.”

When I asked five-time 500cc World Champion Mick Doohan about this style of corner entry, he replied, “I can push the front end-I have pushed the front end. But if you push the front end all the time, you are going to make a mistake. It’s really a matter of riding in the way that gives you maximum security.”

Roberts notes that apexing at traction-limited speed exposes the rider to prolonged high risk of falling, whereas the slower-apexing “point-and-shoot” method cuts the time spent at high risk. The apex-speed loss is then more than made up for by a stronger drive off the turn, with the motorcycle in the more stable (and safer) acceleration mode.

Freddie was able to push the front end from roughly 1978 to 1985, after which perhaps he could no longer summon the necessary clarity of mind.

While many top riders carry with them the handicap of bad habits learned early, great champions have style flexibility. Either instinctively or intentionally, they can change their riding styles to exploit new situations. In the current era, Rossi has been champion on 125, 250 and 500cc two-strokes, and now 990cc four-stroke machines-all very different. Veteran race engineer Erv Kanemoto observes that it’s hard to identify riding talent before unfortunate habits become fixed in a rider’s style.

Few riders have been as instinctively able to compensate for machine differences as Spencer. When Roberts confronted Spencer’s corner speed in their final encounters, he changed his own style at the very end of his career-a rare thing. Lesser men are able to alter style enough in practice to prove the changes work, but under the pressure of actual racing, they regress-and slow down.

Fast information gathering, analysis, storage and retrieval is another ability of champions. When Kevin Schwantz took part in a Yoshimura Suzuki Superbike audition at Willow Springs in the mid’80s, an observer saw that Schwantz never took the same line or made the same moves twice in a given corner. To extract the maximum information from track and motorcycle in the few laps he was given, he was running at least one new experiment per lap in every corner.

Doohan had the reputation of riding every lap-practice, testing or race-at the maximum.

“That’s your opportunity to learn something,” he said plainly. “You only learn something if you ride at 100 percent, so any lap ridden at less than that is a waste.”

Cook Neilson, former editor of Cycle magazine, said of Gary Nixon, “He never took the same line twice in a corner.” In an era in which most riders rode a geometric line of maximum radius, Nixon found ways to ride anywhere on the track because he was more racer than rider-he wanted to beat people, not clocks.

I watched Lawson practice at Laguna Seca in the early Eighties on the Muzzy Kawasaki 1025cc Superbike. Each time he came down the Corkscrew, it was a different performance. Those riders who believe they will become faster through “seat time” are disappointed. Riders go faster when they learn specific things. This cannot happen by mindless repetition. The riders I have known who are extremely serious about going fast have imposed a learning self-discipline that is urgent and scholarly-like that of combat aviators.

Some riders-such as four-time 250cc World Champion and current MotoGP competitor Max Biaggi-compete off the track as well as on. Doohan’s view: “Any competitive activity that is not directed at winning on Sunday is wasted.”

Some riders have little idea how they achieve their lap times. Others, like Roberts, have analyzed everything they do and can describe it step by step. Roberts’ experience at Brands Hatch in 1974 changed him from a hot kid with natural talent into something beyond.

First, he was humiliated by three British riders who were faster than he was, despite his being on a factory Yamaha. Deciding that riding harder > was a blind alley (riding harder may be nothing but insisting on one’s mistakes), he went up into the back of the Goodyear truck and made himself a private space by stacking tires.

“I stayed in there for a couple of hours, going over in my mind what I’d seen,” he said.

He found he could call up from mem ory a frame-by-frame analysis of all that had happened in practice, and that he could extract usable information from this about what specific things the others were doing differently. Finally, he came out of the truck and told his crew chief Kel Carruthers that he was ready to go out again.

“I went out on the bike, took two laps to warm up the tires, and the third lap was right on the lap record. I was impressed. After that I went back up in the truck again and played it all back in my mind. When I ran the next practice, I had a new lap record.

“I had to go almost all the way to being national champion before I learned that the most important tool for going fast was the mind.”

Roberts also put a high importance on concentration, which is a one-word name for the special streamlined state of mind necessary for going fast. Concentration clears the mind of irrelevant tasks, making it into a single-purpose device for the task at hand. This is like loading specialized software that has been made to run ultra-fast by stripping out all but essential steps. From his description, his concentration was something he could control, focusing intensely at critical moments, or emerging from tactical intensity to consider strategic matters.

“My reflexes aren’t all that fast,” Roberts said in 1980, “so I have to get a lot of my thinking done ahead of time. I think of my mind as a big velcro board, with packets stuck to it. In each packet is what I have to do in specific situations, specific corners, or when other riders are present. When a situation comes up, I don’t have to think about it—I just pull down that packet and do it.” Programmers call these packets “subroutines.”

After the better part of a season looking at the tail end of Bayliss’ factory Ducati as the Australian took win after win, Edwards finally broke through with a victory at Laguna Seca this past July. Going into Assen, Edwards had five consecutive wins and won the first race going away. In the second race Bayliss pushed harder than ever, hard enough to crash and lose what was left of his points cushion as Edwards won.

More than one experienced person in the paddock has said of Bayliss that he doesn’t really know where the limit is-he just keeps pushing harder. In human character, our strengths are also our weaknesses.

The discipline to maintain pressure from behind, without the “emotional fuel” of winning, requires special strength. In the 1980s contests between Spencer and Lawson, Lawson was always there, always close, always going fast. Spencer won races, but Lawson won more titles. There are many kinds of champion. Many riders go faster when challenged, only to relax their pace once passed, but three-time 500cc World Champion Wayne Rainey rode as hard in fifth as in first. The drive to do this kept him always able to exploit any change in the race ahead of him.

When Rainey went to Europe, Baldwin predicted the Californian would succeed. Why? “I could never make myself completely trust the front tire,” Baldwin says. “But Wayne had the ability, when the race started, to just decide to trust it, and ride as though it would grip every time.”

This ability to look right through apparent problems to a successful result frees the rider from the searching fingers of doubt. Top riders expect to win every race-Bayliss told me this recently in so many words. Once Doohan knew his own skills and equipment were the equal of any, it became intolerable not to win every race. Carmichael’s intolerance of losing drove him to actually win all 24 motos of this year’s 250cc AMA Outdoor Motocross Championship, after a season of nearly equal crushing dominance in Supercross. Edwards achieved the freedom of this outlook only after he’d begun his World Superbike career, and renewed it after his 2002 turning-point win at Laguna Seca. Eric Bostrom speaks of “not thinking on the dark side.”

All the high-flown qualities of mind-concentration, discipline, judgment, intelligence-are nothing without the power of desire. Strong motivation rejects failure as it single-mindedly prepares all the tools that pull success closer. Action is empty without desire, but desire forces a way to win.

“Why not me on the top of the box?” Just do it. n

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontBeginner's Luck

December 2002 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Thousand Mile Ride

December 2002 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCFlexi-Flyers

December 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

December 2002 -

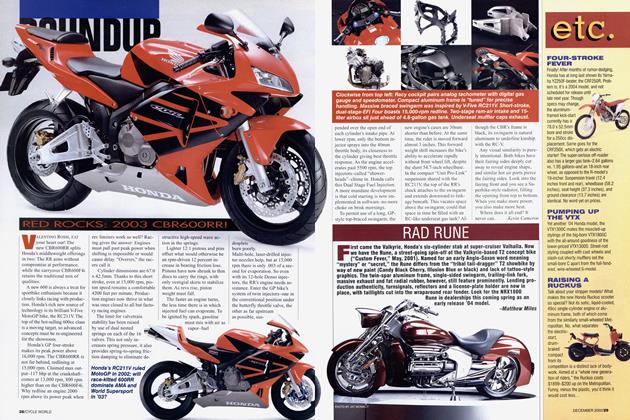

Roundup

RoundupRed Rocks: 2003 Cbr600rr!

December 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

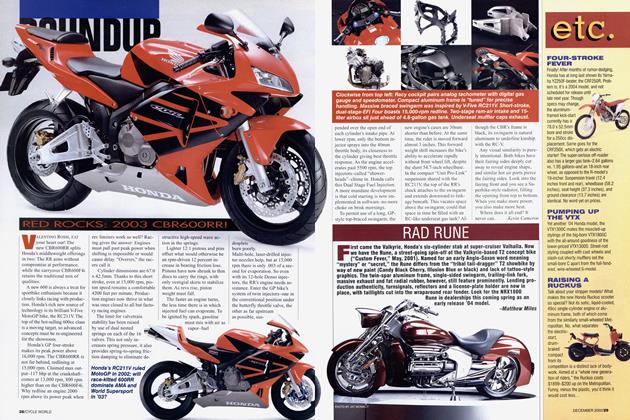

Roundup

RoundupRad Rume

December 2002 By Matthew Miles