Hard Times

TDC

KEVIN CAMERON

THIS ECONOMY IS A HARD CRUNCH for the motorcycle industry. Even as many experts tell us that recovery is beginning, a great deal of money is still on the sidelines, kept out of play by a feeling that markets are unreliable, that they don't "feel right." People are understandably nervous—even if they have jobs. Also on the sidelines are many who might otherwise have bought cars, big-screen TVs—and motorcycles. People are out of work, and some speak of the present time as a "jobless recovery." That means that while money may again be moving and that money is being made by investors, the shrunken economy can't afford to rehire the 10 percent of the workforce reported as unemployed.

If we compare sales of road-going motorcycles, year-to-date, for this year and last year, we find they are off just over 40 percent. Off-road isn't quite as bad (28 percent). Even Harley reports 2009 revenue is off by 23 percent from 2008, with income dropping by almost 90 percent. In the fourth quarter of 2009, Harley revenue was off 40 per cent versus the same quarter in 2008. It's tough all around.

These are serious numbers. Every productive enterprise has a break-even level of production. One factory I visited many years ago was said to break even at 60 percent of its maximum produc tion. When demand shrinks, production has to be cut, and if it drops below the break-even point, serious money is lost.

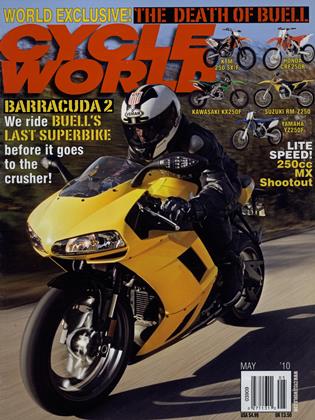

Essential activities like new-model development, research and advertising (a part of which is racing) are planned on the basis of continuing healthy sales and income. When sales drop as they have, things have to be cut. The flow of new models throttles to a trickle. Consumer magazines grow thin as pages of advertising are cut. And we have seen that Honda and Kawasaki have announced plans to give AMA Pro roadracing a pass for the time being.

On the international scene, the Motor Sports Manufacturers' Association (basi cally, the Japanese Big Four plus Ducati) went to Dorna (Spanish MotoGP-rights holder) and asked for money-saving re structurings of racing classes. This year in MotoGP, each rider will have only six engines for the season-a big reduction from boom years when there was an engine for every practice and race. Race engines this year must be capable of going 2000 kilometers (1240 miles)-a giant change from a past in which some components had to be changed daily (clutch baskets, pistons, valve springs). Why not just quit racing? Can't do that! It has become essential to motorcy cling's worldwide appeal.

Two conflicting models exist for what will happen next. The "accordion model," which I heard about from a BMW financial planner a year ago, holds that this recession is like others in the past: as normal as the rise and fall of the tides or the cycle of summers and winters. In a year or two, it will be business as usual as sales swell back to healthy numbers.

The other view looks at history for inspiration. In the 1950s, European motorcycle manufacturers saw their sales shrink almost to zero as slightly more prosperous consumers put what little money they had into cars, giv ing up motorcycles as basic transpor tation. That time, it took 20 years for the European motorcycle market to come back-the time necessary for the European economy to become strong enough to contain many with income levels sufficient to afford both a car and one or more motorcycles.

In similar fashion, some analysts say that the U.S. core customer base for motorcycles will not come back for two to three years because of the combina tion of unemployment, underemploy ment and flat wages. This is causing more than just the Big Four to look to Asia-recovering faster than the U.S. or Europe-for future profit. Harley re cently announced a sales push in India.

Yamaha is said to have undertaken considerable R&D last year-projects which must be completed in order to have any value. In an effort to cut seri ous losses of nearly $2 billion in the past year, the company has offered 800 engineers early retirement.

If a weak market lasts several years, a financially distressed maker might com pare the uncertainty of its motorcycle activities with more assured profit from its other business enterprises. A billion dollars of motorcycle production tooling would be a lot of overhead to carry just on the chance that $10,000 sportbikes will come roaring back next year.

What to do? One plan would be to abandon ship, moving flexible tooling to other products and finding Chinese, Indian or Indonesian buyers for the rest. Another plan would be to aim sales at Asia, suck it up and hope for the best.

Honda seems to have done what General Motors did in 1925-cut fixed costs by all possible means. This has worked well enough to result in an op erating profit this year, allowing Honda to raise R&D spending for next year. As Honda engineer Shuhei Nakamoto told me at the Indianapolis MotoGP last summer, "This year, we are work ing on many small problems, but next year-new concept!"

It is possible that what we are see ing in MotoGP may be a model for the industry as a whole. That sport is shift ing away from being an R&D-intensive, all-out techno-war to being a managed spectacle that puts sizzle in the place of steak in the name of cutting costs. The new Moto2 class offers just as much acreage for eye-grabbing paint jobs and commercial messages but with zero en gine R&D cost. Maybe motorcycling in general will do something similar-pro duce appealing, trendy products long on focus-group-refined edgy hipness but shorter on titanium, carbon fiber and whose-is-biggest performance numbers.

Meanwhile, a new generation arises, which may care as little for the de tails of how a motorcycle works as it does for the thermodynamic cycle of the home refrigerator. The bandwidth of life swells every day as everything clamoring for our attention becomes just another entertainment channel. What if tomorrow's buyer is minimally concerned with what the motorcycle is and much more interested in how it looks and how it makes the opera tor feel about himlherself? As if a rac er told his crewchief, "Forget the lap times, man. How'd I look?"

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontGreat Books

May 2010 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

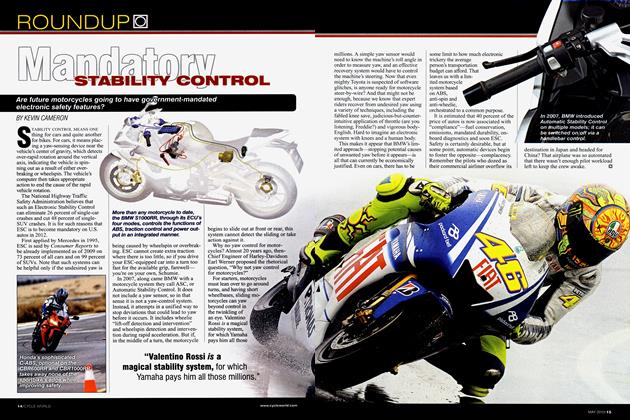

RoundupMandatory Stability Control

May 2010 By Kevin Cameron -

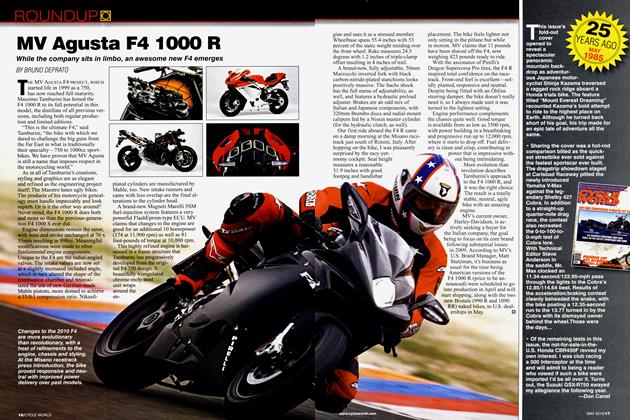

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago May 1985

May 2010 By Don Canet -

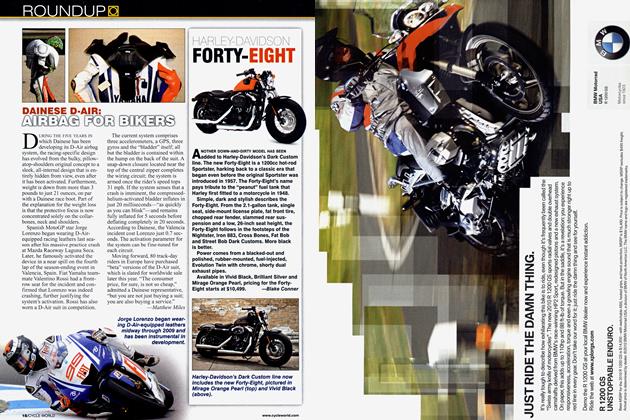

Roundup

RoundupDainese D-Air: Airbag For Bikers

May 2010 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupPitch, Putt And Peruse

May 2010 By Robert Stokstad -

Roundup

RoundupUps & Downs

May 2010