Places of Work

TDC

Kevin Cameron

WHERE CAN I WORK ON MY MOTORcycle? My first bikes, like it is with so many people, were worked on in college rooms, in clear violation of reasonable rules. There we were, my roommate and I, with most of a BMW R27 stood up on its hind wheel in the elevator, and with Mr. Buildings and Grounds sprinting toward us. The doors smoothly closed and we became anonymous. Inevitably, in a few days we stood before the housemaster facing charges that we had “slammed the elevator door” in the face of authority.

My roommate, tall, thick-spectacled and grave, said, “Sir, if I may be permitted to point it out, the elevator doors close at only one rate—that which is regulated by the manufacturer. The doors cannot slam. They merely close.” Continuing the charade, the housemaster pulled at his pipe (always the refuge of slow-thinking administrators) and promised to “look into it.”

In retrospect, that concrete-and-steel tower of modern architecture may have been the poshest workshop I ever had.

Next came the front room of my first apartment, where I learned several useful lessons, one of which related to dropping cam-chain master links into an assembled engine. But it was grand to have toolboxes set not on the floor but at working height, and to have heat and light. We would set forth from that modest R&D center for our first roadrace, at Vineland, New Jersey, and I would spend a winter trying to make sense of every available magazine photograph of two-stroke exhaust pipes. I also learned to degree aftermarket camshafts, discovering in the process that the numbers on the timing card spec sheet may not refer to the actual lobes of the product in the box.

We’ve all worked in basements, and that was my next stop, in a nice residential neighborhood. Sunshine yellow did wonders for the dreary gray of the stone foundation walls. Overhead fluorescent lighting, work tables and a “Gunk” tank gave the place a serious tone. A row of Yamaha 250s—TDIBs and Cs—looked just enough like photos from Isle of Man workshops to add heartbeats. More heartbeats attended the late-night Big Lift, as bikes were heaved up the stairs to the vans waiting outside to carry us all to places like Harewood Acres, Mosport or Nelson Ledges. That’s not as bad as it sounds—those were 225-pound bikes, not today’s 400-pounders (sounds like a new burger). The gasoline we burned in those days would cost a fortune now and might earn us a Black Arrow or two, shot in renewable appropriatetechnology fashion from green bows. My apologies for having enjoyed every minute. What did we know of the world to come?

In that time period, I learned to service pressed-together crankshafts, but my notions of proper jetting remained stuck at chocolate-brown. It was a pleasure to be able to lay out clean, fresh engine parts and to assemble in good light, with everything at hand.

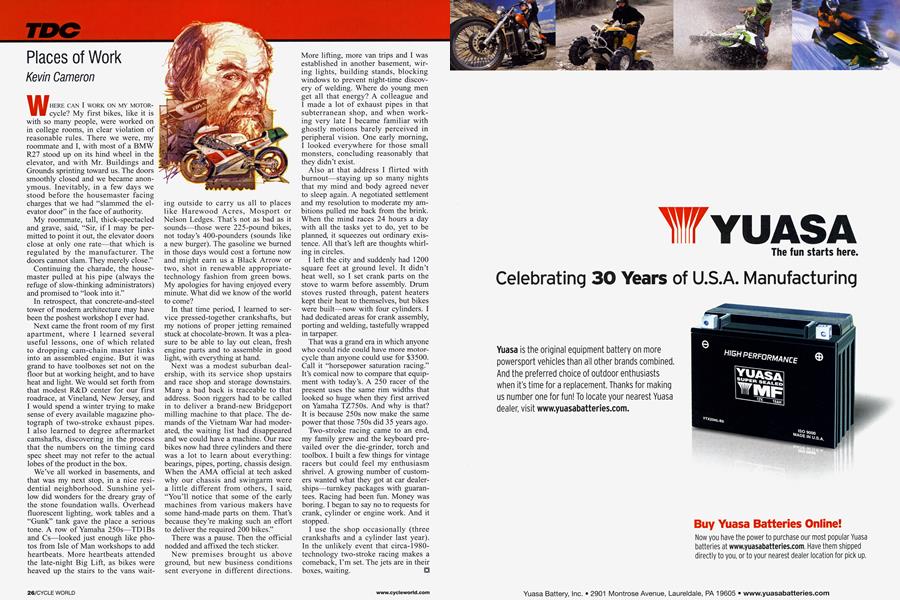

Next was a modest suburban dealership, with its service shop upstairs and race shop and storage downstairs. Many a bad back is traceable to that address. Soon riggers had to be called in to deliver a brand-new Bridgeport milling machine to that place. The demands of the Vietnam War had moderated, the waiting list had disappeared and we could have a machine. Our race bikes now had three cylinders and there was a lot to learn about everything: bearings, pipes, porting, chassis design. When the AMA official at tech asked why our chassis and swingarm were a little different from others, I said, “You’ll notice that some of the early machines from various makers have some hand-made parts on them. That’s because they’re making such an effort to deliver the required 200 bikes.”

There was a pause. Then the official nodded and affixed the tech sticker.

New premises brought us above ground, but new business conditions sent everyone in different directions. More lifting, more van trips and I was established in another basement, wiring lights, building stands, blocking windows to prevent night-time discovery of welding. Where do young men get all that energy? A colleague and I made a lot of exhaust pipes in that subterranean shop, and when working very late I became familiar with ghostly motions barely perceived in peripheral vision. One early morning, I looked everywhere for those small monsters, concluding reasonably that they didn’t exist.

Also at that address I flirted with burnout—staying up so many nights that my mind and body agreed never to sleep again. A negotiated settlement and my resolution to moderate my ambitions pulled me back from the brink. When the mind races 24 hours a day with all the tasks yet to do, yet to be planned, it squeezes out ordinary existence. All that’s left are thoughts whirling in circles.

I left the city and suddenly had 1200 square feet at ground level. It didn’t heat well, so I set crank parts on the stove to warm before assembly. Drum stoves rusted through, patent heaters kept their heat to themselves, but bikes were built—now with four cylinders. I had dedicated areas for crank assembly, porting and welding, tastefully wrapped in tarpaper.

That was a grand era in which anyone who could ride could have more motorcycle than anyone could use for $3500. Call it “horsepower saturation racing.” It’s comical now to compare that equipment with today’s. A 250 racer of the present uses the same rim widths that looked so huge when they first arrived on Yamaha TZ750s. And why is that? It is because 250s now make the same power that those 750s did 35 years ago.

Two-stroke racing came to an end, my family grew and the keyboard prevailed over the die-grinder, torch and toolbox. I built a few things for vintage racers but could feel my enthusiasm shrivel. A growing number of customers wanted what they got at car dealerships—turnkey packages with guarantees. Racing had been fun. Money was boring. I began to say no to requests for crank, cylinder or engine work. And it stopped.

I use the shop occasionally (three crankshafts and a cylinder last year). In the unlikely event that circa-1980technology two-stroke racing makes a comeback, I’m set. The jets are in their boxes, waiting.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontSeizing the Means of Production

FEBRUARY 2010 By Mark Hoyer -

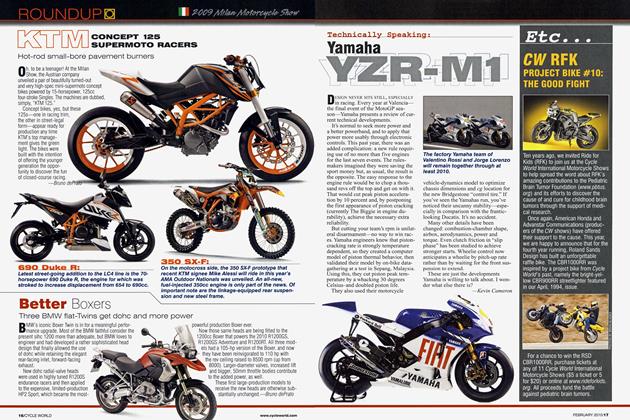

Roundup

RoundupSexysix

FEBRUARY 2010 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

RoundupKiller Concepts

FEBRUARY 2010 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

Roundup2010 Mv Agusta F4

FEBRUARY 2010 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

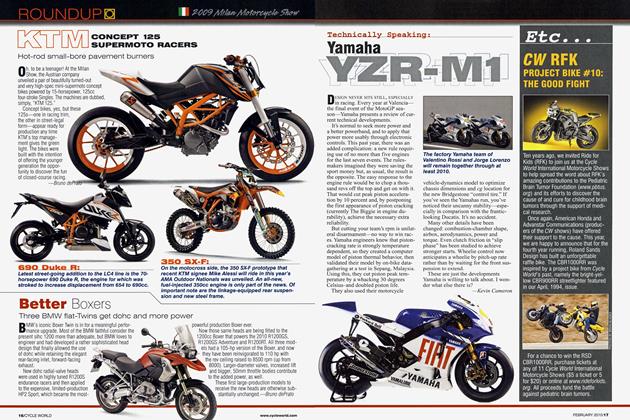

RoundupKtm Concept 125 Supermoto Racers

FEBRUARY 2010 By Bruno Deprato -

Roundup

RoundupBetter Boxers

FEBRUARY 2010 By Bruno Deprato