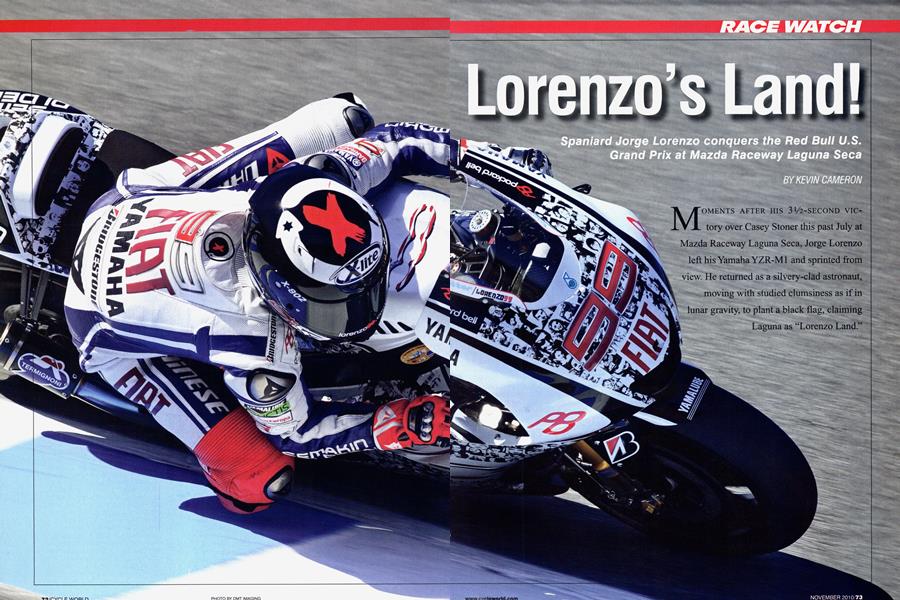

Lorenzo’s Land!

RACE WATCH

Spaniard Jorge Lorenzo conquers the Red Bull U.S. Grand Prix at Mazda Raceway Laguna Seca

KEVIN CAMERON

MOMENTS AFTER HIS 31/2-SECOND victory over Casey Stoner this past July at Mazda Raceway Laguna Seca, Jorge Lorenzo left his Yamaha YZR-M1 and sprinted from view. He returned as a silvery-clad astronaut, moving with studied clumsiness as if in lunar gravity, to plant a black flag, claiming Laguna as “Lorenzo Land.”

Lorenzo won the starting-line drag race but was left behind in a hectic Turn 2 push-and-shove as Honda’s Dani Pedrosa took the lead. Was this it? Would this be another of Pedrosa’s signature lead-and-leave wins? A year ago, HRC VP Shuhei Nakamoto had told me, “Next year, new concept!” and this Honda is certainly faster than before— but at a cost in stability. We are used to seeing the smoothness of Valentino Rossi’s and Lorenzo’s mature Yamaha Mis, and this year, to Nicky Hayden’s betterment, the Ducatis have smoothed out. But as Pedrosa accelerated off turns, his front end jerked up, stabilized, then popped up more an instant later. All its motions were choppy. Didn’t Honda hire away Yamaha’s key software writer, Andrea Zugna? Where is the rate-sensing wheelie control, then?

Last year at Indianapolis, Pedrosa had been the Karate Kid on the Honda, chopping it hard through maneuvers that wasted no time at all. He was doing that now, leading Laguna, looking like a runaway.

Earlier drama was Lorenzo’s attack on Ducati’s Stoner. When I’d asked Stoner

why his machine is now so much more stable, he’d replied, “It’s not stable.” To the onlooker, steady weave oscillation in comers looks unstable, but to riders, unstable means unpredictable. In 1972, Yvon Duhamel’s Kawasaki Triples looked wildly unstable, but to him, their motions were predictable and thus okay. Now the Ducati looks stable, but it isn’t. Despite this, Stoner had been very fast all weekend.

Stoner lost the front a couple of times in early going, costing him some essential confidence. On Lap 5, his tire let go again and Lorenzo came past on the inside of Turn 3. (“Casey made a mistake and I pass him,” he later said.)

Now for Pedrosa: Lorenzo described his countryman as “braking at the limit every time. I think Dani can crash.” It happened on Lap 11 in Turn 5.

The rest of the race has been described by some as “Lorenzo cruises,” but it was clear that every tenth of a second had to be won by hard grinding, for Stoner wasn’t giving up the best performance of his season. Both men were lapping at qualifying speed. By Lap 15, Lorenzo had 1.75 seconds and by Lap 27, 4.15. Now, with five laps to go, Lorenzo relaxed by a full second. Did he have a fuel economy warning? At the end, he had the aforementioned 3-plus seconds in hand. Lorenzo was paying attention.

Underlying this drama was an administrative issue: the six-engines-per-rider-perseason limit. Lorenzo has had one fiery parts-out-the-bottom blowup, and there is one engine pushing a little oil. By the mies, the leaker can’t be serviced or even examined, but it may be capable of hundreds of miles more mnning. Teams with no wins for two seasons are being allowed nine engines. If you use all your engines, you start from pit lane 10 seconds down. Will MotoGP rights-holder Doma permit a purely administrative mle to determine a champion? Stay tuned for riveting updates on engine life.

Sunday’s sub-drama was Rossi’s progress from sixth to third at the finish with a speed-healed broken leg. (I saw him in Yamaha’s hospitality area, walking with his two blue sticks, one of which he would later toss into the crowd during the podium ceremony.) Ben Spies was soon passed but Andrea Dovizioso (on the second Repsol Honda) required longterm effort, the pass coming on Lap 25 on entry to Tum 11. Dovi fought back to within .138 seconds of Rossi at the end, so this was no cruise, either. Americans Hayden, Spies and his Tech3 Yamaha teammate Colin Edwards would finish fifth, sixth and seventh, respectively.

The top three teams are all on the pace, all with advanced valve control (pneumatic springs or desmo), with full electronic technologies and the ability to race nearly to the finish on 5/2 gallons of fuel. At normal four-stroke-specific fuel consumption, that’s a race average of 90 horsepower. If, as Brembo tells us, the bikes are on the brakes roughly 25 percent of the time, that average power rises to 120. If a top Yamaha, Ducati or Honda makes 220 hp, 120/220 is a 55 percent duty cycle. This, in turn, shows us why more power so seldom wins races: Winning is about part-throttle speed around comers and beginning acceleration as early as grip permits.

That’s why MotoGP has turned into:

1) a game of top riders, because electronics can’t help lesser riders judge

comer entry speed, duke it out with strategy-wise rivals or make the tires last to the end; 2) amazing tire grip—look at the lean angles and comer speeds; and 3) throttle optimization.

Over and over, a team has added horsepower—as Jorg Möller said years ago,

“It’s only money”—and has found its riders going backward at half-distance as their tires “went off.” More power works the chassis harder and requires more sophisticated electronic protections, so the tire spins and slides more. A look at Laguna top speeds shows Stoner on top at 166 mph. Rossi’s Yamaha was second at 163. But right with him was Roger Lee Hayden on the LCR-leased Honda, who would finish 11th. This game is not power; it is disciplined, usable power.

The concept of a “virtual powerband” depends on that modest 55 percent duty cycle. With part-throttle as the usual condition, the throttle-by-wire can be programmed to compensate for the engine’s natural torque peaks and dips by closing and opening, thereby simulating a predictable, flat torque output that is easy to use (like the “rain mode” on the

BMW S1000RR). This allows higher engine tune, which, without electronic help, would be unrideable.

Traction mapping makes use of the fact that every cycle of the traction-control system is a measurement of the track’s coefficient of friction at that point. By pairing these measurements with GPS data, a traction map of the fast line in each comer is constructed. This map enables the throttle-up through each comer to be smoothly programmed very near the limit, avoiding traction control’s series of time-wasting slips and grips. You still hear plenty of engine cuts on the circuit—pop, pop, pop. This is because no rider can be on the ideal line in every comer of every lap, so the traction control must then take over. Traction control itself has multiple levels, beginning with ignition retard, moving on to throttle modulation and, when there’s need for very fast response, actual fuel or spark cuts.

Recently, the Yamahas have looked very stable, but Spies’ crew chief, Tom Houseworth, said, “If we go short [in wheelbase] to get more grip, we can get our bike unstable, too.”

What is different between World Superbike (where Spies was champion last year) and MotoGP? “With these bikes, the mass is so centralized,” Houseworth replied. “We make little teeny changes. We couldn’t get the bike stopped, so we lowered the rear—half a millimeter is all it took! With the Superbike, the required change would be 5 millimeters.” Stoner leaves Ducati for Honda at the end of this season. I asked him what has changed with the adoption of the plastic chassis. “The carbon-fiber chassis? The old steel-tube chassis was too soft to hit the same place on the track two laps running.”

Even the lowly spectator (me) could see the similarity between the instability of Stoner’s Ducati in 2008 and the famed “Superbike wallow” that tube-framed Ducatis have displayed. Edwards had said in 2002, “Yeah, they wallow, but they dig in and go around the comer.” (At the time, Edwards added, Honda’s RC51 chassis was twice as stiff). When the Honda was stiffly skipping from one bump crest to the next, the Ducati’s lateral softness kept its tires in good track contact at full lean.

I suspect the carbon chassis has allowed Ducati to keep that lateral flexibility, yet limit torsional twist that leads to wallowing. That’s one of the beauties of directional materials.

Notice two things here: First, Ducati giving up its trellis frame is as great a measure of desire to win as was Yamaha’s 2004 adoption of four valves in place of its signature five valves. Second, Stoner’s imminent departure allows him to be a bit more candid than usual.

A concern at Yamaha is that Masao Furusawa, currently head of motorcycle engineering and the planner behind the Yamaha Ml’s ascent to dominance, is to retire at the end of this year. “I have been doing this work for seven years,” he said at Laguna. “It is time to do something else.”

I hope to ask Rossi about this at Indianapolis. He is going to Ducati next year. Could he have as close and fruitful a relationship with Filippo Preziosi as with Furusawa? Will Yamaha carry on as before? Only time can answer.

I asked Stu Shenton at Suzuki if it were possible to imagine an active stability system for a motorcycle. This would modulate the throttle out of step with the weave mode (riders call this “pumping” or “bucking”) to suppress it.

He replied, “If you can think of something, and it’s not too silly, give the software writers a couple of weeks and they’ll come up with something.”

I asked if the extra research necessary to make pistons, valve sealing and bearings last 1200 miles was cheaper than the cost of building the many more engines used in the past. “It does save the factories money,” Shenton admitted.

On the track, I could see money saved in another way: Suzuki riders Loris Capirossi and Alvaro Bautista resorting to high corner speed in place of acceleration. Every team must make such choices when economic reverses cut research.

In more prosperous times, MotoGP foretells the future of motorcycling through its rapid development. Today, some pundits speak of “the end point of motorcycle design.” I think not.

R&D funds aren’t gone forever. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMotor. Cycle.

November 2010 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

RoundupBuell Fights Back

November 2010 By Steve Anderson -

Roundup

RoundupItalian Triple Threat

November 2010 By Jeff Robert -

Roundup

RoundupUps & Downs

November 2010 -

Roundup

RoundupTeam Cycle World

November 2010 By Paul Dean -

Roundup

RoundupHeadbanger

November 2010 By Bruno Deprato