Clipboard

Rubber run-in

December is Dunlop tire test time. Most teams bring last year's bikes for this three-day session because the machines are ready. The goal is not quick lap times, but to discover how the new tires fit into existing chassis setups, and to make necessary adjustments. This year, the top men quickly got down to lap times in the mid-1:51s, so that was this year's "zone."

New Vance & Hines Ducati rider, Australian Troy Bayliss, was seeing the big oval for the first time. As Dunlop technician Jim Allen put it, Bayliss “put his head down right off the bat.” He was fast man of the test, with laps in the bottom 1:50s. These times are unrelated to actual Daytona qualifying times because no qualifying tires were run in the test, and because circuit conditions improve in March with warmer weather and more bikes on the track.

Vance & Hines has essentially started over with new riders and mechanics. “We tested at Daytona in August, and I felt then we could really do the business with Ben Bostrom,” V&H crew chief Jim Leonard said. Then, Ducati teamed the 1998 AMA Superbike Champion with Carl Fogarty in World Superbike. Meanwhile, Anthony Gobert’s goals presumably lie outside racing. “There was a lot (for Bayliss) to take in,” Leonard added, “different bike, different team, the super-speedway.”

Bayliss, who is 29 years old and had his wife and two children with him, is joined on the team by exYoshimura Suzuki rider Steve Rapp.

Fortunately, the Ducati is already an established performer. Leonard said, “I don’t foresee any major improvements. There is a new Marelli (enginecontrol electronics) and there’ll be new front and rear suspension. We have a good setup, with info for each track.”

Honda rolled out its new RC51 V-Twin, and newly recuperated team rider Miguel Duhamel needed only six laps to get into the zone. Wonderkid Nicky Hayden also rode the bike, crashing at low speed. Kurtis Roberts achieved the second-best time of the test on last year’s RC45, which visibly had top end on the RC51.

Honda team manager Gary Mathers says the RC45 was at the test “just for something to do,” and that Honda Japan is still requiring the return of the V-Fours. The Honda presence at Daytona will be all RC51.

“They get through the infield really well,” Mathers added. “Our split times are the best we’ve had. The bikes are stiff. They came from Phillip Island, which is real smooth, but their transition onto the banking was train-straight. We’re pretty impressed. They were only test motors with steel rods in them. The chassis is much more finished than we thought it’d be-they must be secondor thirdgeneration. Miguel said the bike didn’t feel fast anywhere.”

Of the Honda, Leonard said, “In the infield, it definitely had some acceleration.”

Mathers confirmed that the RC51 was slower on top than the V-Four by about 8 mph. The combination of a good Daytona infield time and not feeling fast is a good one, indicating that the engine pulls strongly everywhere, rather than having a hard “hit” that can upset off-corner drive. Historically, Daytona destroys new designs, but Honda’s test department is experienced. This was a promising beginning.

Yoshimura Suzuki’s Mat Mladin carries the number-one plate this year, and he set an example of studious, professional testing. He and his crew concentrated on weak areas, working especially on setup for the infield dogleg.

Mladin’s approach illuminates by contrast a problem that afflicts some hot, young riders. Riders start early now, with some pundits claiming, “If you haven’t won some kind of minibike championship by the time you’re 10, forget Pro racing.” This is an extreme view, but many top riders grow

up on bikes and competition. This means that 16-year-old roadrace hopefuls already have superb machine control and a lot of the correct learned behaviors and instincts. When they pull on factory leathers, these skills can initially be very impressive. But there is a gap between the world of instinct and the technical world of machine setup.

Mladin knows that the easier his bike is to ride, the faster he can go for a given level of risk, and the less tired he will be for a possible dash to the finish. Setup is the key, and young hotshots have to learn how to work with their crews to achieve this. Thinking about what used to be instinctive is tough.

Yoshimura team manager Don Sakakura says his team will run 1999-spec bikes all year. New Showa forks showed an immediate improvement in reduced stiction, allowing better use of the throttle across the difficult infield-to-banking transition. Aaron Yates, who rode a Muzzy Kawasaki last season, is back on a Suzuki and says, “It’s a completely different bike now.”

AÍ Ludington, formerly Miguel Duhamel’s crew chief at Honda and now with the new, post-Muzzy Kawasaki team, said, “These bikes are extremely quick under acceleration. Our riders got with Bayliss and the others, and said they’ve got the Dues handled off the corners.”

Ludington also likes the extra adjustability of the Kawasaki chassis. “Of course, that’s a two-edged sword,” he said. “You have more range for setup, but you also have more room to get lost.” His view is that the Kawasaki now keeps gripping when it should slide, and the resulting slide/hookup cycle upsets the chassis. “We have to make it more slide-friendly,” he added.

Traditionally, Daytona tires have had to be on the hard and slippery side to survive. “Everyone’s usually moaning, ‘no grip, no grip’ at Daytona,” Ludington remarked. “But the tires we’ve had recently really have some traction.”

About instability experienced early in the test, he said, “Yeah, we had some. Some of it was chassis-related, some was rider-related.” When Eric Bostrom saw that teammate Doug Chandler’s bike appeared stable, he asked to try it, and it wobbled worse than his own. Instability is no surprise at Daytona, because at every other track, setup strives to sharpen response, and a highly responsive bike has marginal stability.

What about our American brand, Harley-Davidson? The team is busy. Experimental changes to the VR1000 have evidently affected reliability, for a number of engines were lost at the test. Team members were unavailable for comment.

And the tires themselves? Allen said, “The 16.5-inch rear is well proven-last year’s tire was a big grip uplift. This year, we’re introducing a Daytona-spec 16.5 front. It’s based on the 16.5 front introduced last year. Although the new tire is mainly better from corner apex to exit, Mladin says he can carry more corner speed with it, as well. There’ll be three 16.5 rear compounds, two 16.5 fronts and a couple of safety alternatives.”

While tire tests lack the compelling human drama of a race, they do reveal racing’s active ingredients with unusual clarity. That’s why the tests are fascinating, though often inconclusive.

Kevin Cameron

When worlds collide

Standing in the lobby of the Pasadena Hilton on the morning of the Pasadena World Supercross, Guiseppe Luongo appeared worried. Kingpin of Grand Prix motocross in Europe, Luongo was in America pushing his fledgling World Supercross Series. Scheduled as the second round of a three-race series (four were planned, but Brazil was canceled), Pasadena was to be the first international Supercross race held in the U.S. since the Rodil Cup debacle back in 1985.

Despite Luongo’s best intentions, the series was in trouble before it even began. It was touted as the ultimate America-versus-Europe grudge match, but AMA 250cc National Champion Greg Albertyn (also a three-time world champ) chose not to compete. Team Honda’s Kevin Windham and Ezra Lusk made the same decision. World Champions Alessio Chiodi (125cc) and Andrea Bartolini (500cc) also declined invites, as did virtually every other major European motocross star. Worse yet, Americans Ricky Carmichael and defending World Supercross Champion Robbie Reynard failed to show up at the opening round.

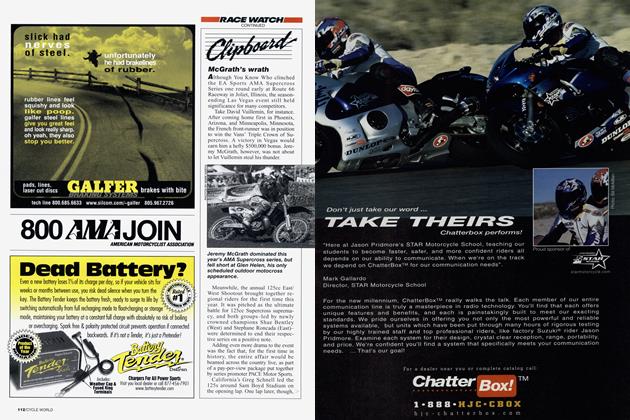

Round one in the Stade de France in Paris was greeted by pouring rain. Despite the horrible weather, there remained a flicker of hope that the series would get off the ground on a positive note. The planet’s most popular motocrosser, Jeremy McGrath, was in France along with a battalion of other talented Yanks. Riding alongside “MC” on the rain-slickened track were Mike LaRocco, Ryan Hughes, Steve Lamson and Jeff Emig. The French were also out in force to defend their nation’s honor.

Thrilled at the prospect of watching the Americans take on their countrymen, nearly 40,000 French fans poured into the big ballyard hungry for action. Upon their arrival, though, many were disappointed to find that Larry Ward, reigning 250cc World Champion Frederic Bolley, GP superstar Stefan Everts and LaRocco were sidelined with injuries.

Then came the main event, and with it a big French haymaker to American Supercross pride. David Vuillemin, after pulling a major holeshot, led all 20 laps to take a convincing win over compatriot Mickael Pichón (remember him?). Emig was third, Lamson fourth and a faltering McGrath, who ended up rolling around in the mud after a tumble, dead last.

Pasadena was scheduled for six weeks later. While the Rose Bowl is known for being a grand, old football stadium, it’s not much of a Supercross venue. Worse, it was overcast and cold (at least by Southern California standards). The result? Only 18,000 fans in a 110,000-seat stadium.

Despite a fair amount of hype and a well-intentioned promoter, the race never amounted to much. Only 18 250cc riders showed up to compete, and Ezra Lusk rode off to an uncontested main-event victory over new Kawasaki recruit Ward, McGrath and Vuillemin. The only bright moment on the dimly lit afternoon was Travis Pastrana’s thrilling charge to the front in the highly competitive 125cc support race.

The final round of the series was held in Leipzig, Germany. For most of the riders, it was a go-through-the-motions event. McGrath waltzed to an easy victory before 15,000 fans. Meanwhile, Vuillemin rode to a safe fourth, giving him enough points to claim the title. When all was said and done, though, nobody seemed to care. Eric Johnson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue