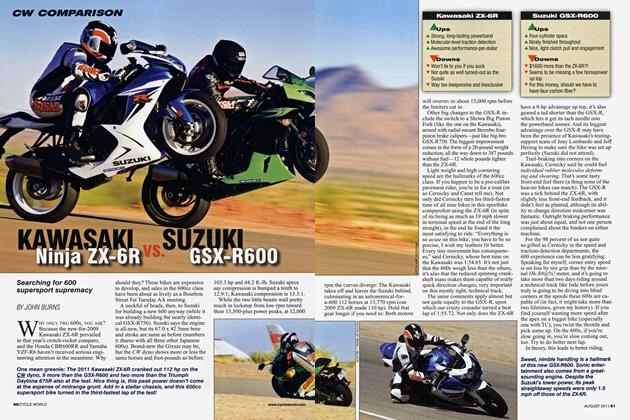

Happy Birthday, Mr. Ninja!

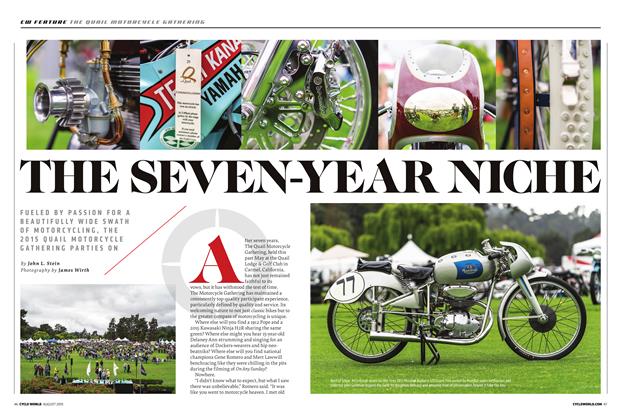

CW FEATURE

George Orwell's timing was a bit off; 1984 was actually a very good year

JOHN BURNS

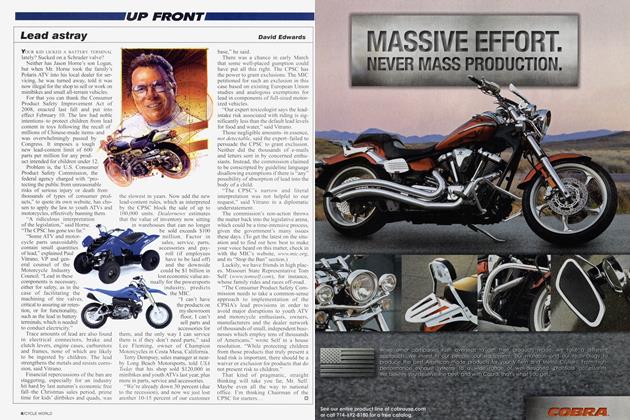

TWENTY-FIVE YEARS AGO, YOU MAY RECALL, there was no Internet, no e-mail, no computer-rendered drawings of new machines that might be in the works... and no real expectation that anything terribly exciting was. In those ancient springtimes-when life ran at a slower pace and the adults were in charge-glossy, rolled-up copies of Cycle World, Cycle (and a bunch of other bike magazines if you wanted them) leapt from the mailbox like Ed McMahon with a big cardboard check. In the backward interior provinces, it was as if the Hubble telescope was out there snailmailing back nude pictures of the Venusian natives, especially when the March,

1984, issue showed up in the middle of a dirty-snowencrusted February.

Some heroic neighborhood figures had Z-l Kawasakis and GSI 100E Suzukis. A fold-out poster of the spaceage-new Honda VF750F Interceptor was on the wall, but an actual Interceptor had yet to be sighted. Ducatis lived on a distant planet the Hubble may have been on its way to. And BOOM! Here came this Ninja thing. What the...?!

Cycle World had to ’splain it to us: “.. .named for a secretive, powerful, ruthless cult of hired assassins. Japanese history tells us Ninja were deadly effective, capable of terrorizing larger forces... The Kawasaki competes not with sheer numbers and size, not with brute horsepower, but with a combination of compactness, agility and power.”

The stars were aligned. Kawasaki’s director of marketing at the time, Mike Vaughan, had somehow graduated from college with a double major in Journalism and Chinese History, and in his spare time was plying the local SoCal waters in a sailboat named Ninja. It was Vaughan’s idea to call the new bike Ninja. Furthermore, James Clavell’s best-selling novel Shogun had just been made into a wildly successful TV mini-series starring Richard Chamberlain, and those five prime-time nights launched a whole new fascination with Eastern culture in the U.S., to include sushi. Given all that fortuitous tailwind, naturally, Kawasaki

USA’s advertising agency at the time wanted to call the new bike Panther.

The U.S. press was introduced to the GPz900R Ninja at Laguna Seca on December 7, which might have been ironic if not for the fact that the Japanese tend to schedule lots of intros on that day. Maybe they are making a point? For once, Cycle World’s own John Ulrich made news by not throwing the new bike down the track, though Cycle’s Mark Homchick crashed a GPz750 so hard in pursuit of Wayne Rainey that it cracked the engine cases. Hail Kawasaki, on a serious ego roll in those days with Eddie Lawson and Wayne Rainey racking up national championships, managed to get Monterey Airport to let them use a runway for quarter-mile testing, where the new Ninja proved itself to be the fastest production machine ever unleashed, capable of running low 1 Is at around 120 mph. In a final and powerful below-the-belt marketing coup de grace even by motorcycle industry standards, Kawasaki offered to sell new Ninjas to members of the press corps for the low, low sum of $1500; retail was $4399. (Few moto-joumalists accepted the offer at the time, bless their integrity-driven little hearts, and a quick check reveals the offer has, unfortunately, expired.)

Well, it’s a nearly forgotten machine now, but that first Ninja laid down the basic pattern for the way we’ve been doing it ever since, sportbike-wise: Liquid-cooled, dohc Four; 16-valve head, cams chain-driven from one side for narrowness; single-shock rear suspension; lighter and more compact than the competition-and all of it covered in what looked like swoopy, aerodynamic bodywork at the time. Heck, the original Ninja was the first bike with the cool aircraft-style fuel filler that’s now standard on all sportbikes.

Racing shmacing, the Ninja’s 908cc were too many to let it run in AMA Superbike, and the purists were busy being enthralled by the more sophisticated Honda VF750F Interceptor, anyway. Sales-wise, the purists were no match for Tom Cruise rolling around San Diego helmetless on a Ninja two years later in Top Gun, and the Honda’s whirl-agig V-Four engine was no match for the Ninja’s robust and revvable six-speed ripper, either.

Cycle magazine, rightly impressed with the 900-“It could tum a highway saint into the happiest, hardest road criminal around”-also noted that it marked an important, not altogether positive, change.

“The Ninja says motorcycling is on its way to 150-mph streetbikes; they will be the fastest production road-going vehicles in America. One-fifty bikes will lose versatility because they must be engineered up to those speeds even though the bikes will be ridden-maybe for the most partdown at legal limits.

“Well, welcome to life in the really fast lane, a place where the Ninja already waits, ready to be worn like a red badge of outrage.”

There you have it. It remains to be seen how collectible the original Ninja may be (see “Best Used Bikes,” page 102), but you certainly don’t see many of them rolling around, even in sunny SoCal. In any case, the die was cast, and to millions of non-riding Americans to this day, whether a sportbike is a Honda, a Suzuki or a Whathaveyou, they’re all “Ninja bikes.” □